by Mary Hrovat

I love birds, and I’m obsessed with words, so I suppose it stands to reason that I’m fascinated by the names of birds. I enjoy the “what it says, it does” names such as gnatcatcher and wagtail. (Further investigation reveals that the gnatcatcher family includes gnatwrens such as the chattering gnatwren and the trilling gnatwren, who I assume also do what their names say.) There are also bee-eaters and brushrunners, leaftossers and treecreepers, berrypeckers and foliage-gleaners.

Rollers perform acrobatic flight maneuvers to woo a mate or protect their territory. Bowerbirds build elaborately decorated structures to attract a mate, and some ovenbirds (furnariids) build nests of clay that roughly resemble tiny ovens. Weavers are known for their intricately constructed nests, which they build by weaving grasses and other types of vegetation.

I also delight in names that describe a bird’s appearance: the checker-throated stipple throat and the harlequin duck, for example. The male twelve-wired bird-of-paradise has twelve wiry filaments near his rear that he uses in his courtship display. The prothonotary warbler was named for a yellow-robed notary at the Byzantine court. The rainbow-bearded thornbill is a hummingbird with a narrow glittering band along its gorget (throat feathers) that ranges in color from green to red (more visible in the males than in the females). Read more »

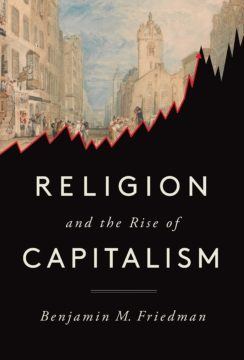

Religion has always had an uneasy relationship with money-making. A lot of religions, at least in principle, are about charity and self-improvement. Money does not directly figure in seeking either of these goals. Yet one has to contend with the stark fact that over the last 500 years or so, Europe and the United States in particular acquired wealth and enabled a rise in people’s standard of living to an extent that was unprecedented in human history. And during the same period, while religiosity in these countries varied there is no doubt, especially in Europe, that religion played a role in people’s everyday lives whose centrality would be hard to imagine today. Could the rise of religion in first Europe and then the United States somehow be connected with the rise of money and especially the free-market system that has brought not just prosperity but freedom to so many of these nations’ citizens? Benjamin Friedman who is a professor of political economy at Harvard explores this fascinating connection in his book “Religion and the Rise of Capitalism”. The book is a masterclass on understanding the improbable links between the most secular country in the world and the most economically developed one.

Religion has always had an uneasy relationship with money-making. A lot of religions, at least in principle, are about charity and self-improvement. Money does not directly figure in seeking either of these goals. Yet one has to contend with the stark fact that over the last 500 years or so, Europe and the United States in particular acquired wealth and enabled a rise in people’s standard of living to an extent that was unprecedented in human history. And during the same period, while religiosity in these countries varied there is no doubt, especially in Europe, that religion played a role in people’s everyday lives whose centrality would be hard to imagine today. Could the rise of religion in first Europe and then the United States somehow be connected with the rise of money and especially the free-market system that has brought not just prosperity but freedom to so many of these nations’ citizens? Benjamin Friedman who is a professor of political economy at Harvard explores this fascinating connection in his book “Religion and the Rise of Capitalism”. The book is a masterclass on understanding the improbable links between the most secular country in the world and the most economically developed one.

Tragically, President Biden’s 21-page “

Tragically, President Biden’s 21-page “

Jesus is reported to have critiqued the seventh commandment as follows:

Jesus is reported to have critiqued the seventh commandment as follows:  by Thomas R. Wells

by Thomas R. Wells

We both have daughters who are good at math, but opted out of advanced math. In so doing, they effectively closed off entry into math-intensive fields of study at university such as physics, engineering, economics, and computer science. They used to be enthusiastic about math, but as early as grade three this enthusiasm waned, and they weren’t alone. It was a pattern we observed repeatedly in their female friends during those early school years, as boys slowly inched ahead.

We both have daughters who are good at math, but opted out of advanced math. In so doing, they effectively closed off entry into math-intensive fields of study at university such as physics, engineering, economics, and computer science. They used to be enthusiastic about math, but as early as grade three this enthusiasm waned, and they weren’t alone. It was a pattern we observed repeatedly in their female friends during those early school years, as boys slowly inched ahead.