by Sabyn Javeri Jillani

Eve was thrown out of heaven because she was a temptress, Sita had a trial by fire because she crossed a line, Lot’s wife (who doesn’t even get a mention by her own name) was turned into a pillar of salt because she was disobedient, but Mary was a saint for giving birth as a virgin. Collectively, the one thing that binds these narratives is a sense of shame. But what if these stories about women were told to us from a different perspective? What if we were told that Eve was a pioneer and a risk-taker for indulging her curiosity about the forbidden fruit? Or that Sita was charitable and fearless for wanting to help an old man in need, Lot’s wife was a patriot and a freethinker for looking back at the land that had raised her, and that Mary was a courageous single mother. How would women see themselves if they grew up thinking of themselves as survivors and not as victims blamed for their choices and penalized for their actions or praised for their purity and silence? What if we saw women for who they are instead of who we want them to be? What if didn’t shame women?

Aib, sharam, haya, izzat, laaj, dishonour — almost every language has a word for shame. And the burden of that shame lies on the shoulders of the female. Because when we grow up in a culture which penalizes women for the consequences of their choices, we internalize a culture of shame — a culture of victim blaming that shames women for asserting their sexuality and agency, shaming them for raising their voices and scrutinizing their bodies. Women learn to curb their curiosity, to stifle desire, and to take ‘submissive and compliant’ as compliments.

As I saw the backlash against Pakistan’s Aurat (Women’s) March unfold this year, I was reminded of the politics of shame that so many women all over the world internalize. I found myself questioning… what does it mean to grow up knowing you are being watched? What does it mean to live in a voyeuristic bell jar where the collective weight of society determines the choices you make? When the length of your skirt can be responsible for your rape, when loving someone your family does not approve of can get you killed, when violence against you is tolerated and even justified because it is your fault that you could not understand the code of honor? From body shaming to slut shaming, the shame is all yours. Read more »

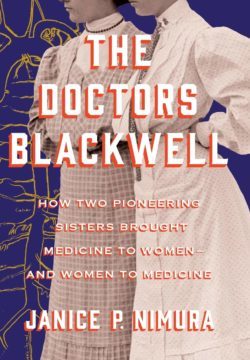

Over recent times, many books have been published with the aim of writing women into history and crediting them for the achievements they have made to the benefit of humanity more broadly. Janice P. Nimura’s The Doctors Blackwell is in that genre of women’s history and she effectively narrates the biographies of the first two remarkable women to study and practice medicine in the United States: Elizabeth Blackwell and her younger sister, Emily.

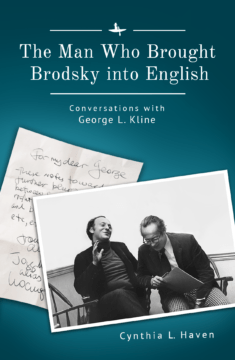

Over recent times, many books have been published with the aim of writing women into history and crediting them for the achievements they have made to the benefit of humanity more broadly. Janice P. Nimura’s The Doctors Blackwell is in that genre of women’s history and she effectively narrates the biographies of the first two remarkable women to study and practice medicine in the United States: Elizabeth Blackwell and her younger sister, Emily. Cynthia, let me begin by asking you to describe your path to the book—a double path that led you to Joseph Brodsky and to George L. Kline.

Cynthia, let me begin by asking you to describe your path to the book—a double path that led you to Joseph Brodsky and to George L. Kline.

Philosophy of science, in its early days, dedicated itself to justifying the ways of Science to Man. One might think this was a strange task to set for itself, for it is not as if in the early and middle 20th century there was widespread doubt about the validity of science. True, science had become deeply weird, with Einstein’s relativity and quantum mechanics. And true, there was irrationalism aplenty, culminating in two world wars and the invention of TV dinners. But societies around the world generally did not hold science in ill repute. If anything, technologically advanced cultures celebrated better imaginary futures through the steady march of scientific progress.

Philosophy of science, in its early days, dedicated itself to justifying the ways of Science to Man. One might think this was a strange task to set for itself, for it is not as if in the early and middle 20th century there was widespread doubt about the validity of science. True, science had become deeply weird, with Einstein’s relativity and quantum mechanics. And true, there was irrationalism aplenty, culminating in two world wars and the invention of TV dinners. But societies around the world generally did not hold science in ill repute. If anything, technologically advanced cultures celebrated better imaginary futures through the steady march of scientific progress.

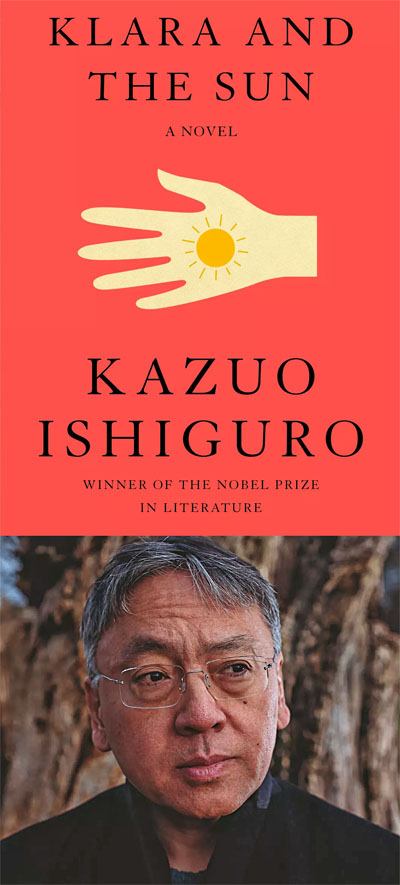

For some time, Sir Kazuo Ishiguro has been slyly replacing Dame Iris Murdoch as the author to whom I most regularly return. His enchanting and disturbing new novel, Klara and the Sun, his first since winning the 2017 Nobel Prize, is unlikely to diminish this trend. I wrote in a

For some time, Sir Kazuo Ishiguro has been slyly replacing Dame Iris Murdoch as the author to whom I most regularly return. His enchanting and disturbing new novel, Klara and the Sun, his first since winning the 2017 Nobel Prize, is unlikely to diminish this trend. I wrote in a  have instrumental value. That is, the value of given technology lies in the various ways in which we can use it, no more, and no less. For example, the value of a hammer lies in our ability to make use of it to hit nails into things. Cars are valuable insofar as we can use them to get from A to B with the bare minimum of physical exertion. This way of viewing technology has immense intuitive appeal, but I think it is ultimately unconvincing. More specifically, I want to argue that technological artifacts are capable of embodying value. Some argue that this value is to be accounted for in terms of the

have instrumental value. That is, the value of given technology lies in the various ways in which we can use it, no more, and no less. For example, the value of a hammer lies in our ability to make use of it to hit nails into things. Cars are valuable insofar as we can use them to get from A to B with the bare minimum of physical exertion. This way of viewing technology has immense intuitive appeal, but I think it is ultimately unconvincing. More specifically, I want to argue that technological artifacts are capable of embodying value. Some argue that this value is to be accounted for in terms of the