by Thomas O’Dwyer

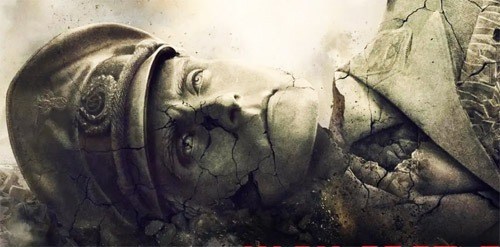

It could have been that simple — the Nazis nuke Washington D.C. and it’s all over. Capitulation follows, resistance is futile. There are plenty of right-wingers in high places — political, military, even cultural, who see this not as a conquest but an opportunity. French Marshal Philippe Pétain and Norway’s Vidkun Quisling had been such people. So too is Obergruppenführer John Smith, their fictional American counterpart in Philip K. Dick’s classic novel The Man in the High Castle. The conquering Nazis offer formerly patriotic American officers light temptations and they casually fall, and then rise. The war is lost, collaboration is inevitable. It’s better to be at the front of the queue, showing some willingness to proclaim (by some small actions) that you accept the times as they are a-changing.

Dick’s novel differs in many aspects from the recently completed Amazon TV series based on it. But in both, the Nazis secure the east side of the country, setting up their capital in New York. The West Coast is messier, but wasn’t it always? On that side of the continent, the Japanese have won. Unlike the stiff-necked and murderously pure Nazis, the Japanese are unabashedly nationalist. They are ruthless occupiers too, but ration their resources to inflict their cruelties on identifiable enemies and resisters.

They care little for non-Japanese, but unlike the Nazis are more inclined to use them than exterminate them. Cheap labour and minions are more useful to the pragmatic Japanese occupiers than white ash falling like snow from the sky on the Nazi side. (It happens on Tuesdays, a highway cop casually explains to a traveller. “Tuesdays they burn cripples, the terminally ill. Drag on the state.”) East Coast, West Coast and then, there is the middle. The heartland, the real America, the cornfields and the cowboys, and the no-longer empty spaces. The middle is oddly unresolved and named the Neutral Zone. It is a strange but useful literary device where former “real Americans” have fled from the Reich and the Empire.

It is that well-known landscape of dystopia after every fictional apocalypse — a mix of wild Westerners (or wild Midlanders), anarchists, war profiteers, pointless rebels with crazy plots to “free” the continent. It’s multiracial too, another literary safety valve. If we accept too literally the axiom that Nazis exterminate non-Aryans (and even the genetically defective children of their own elites), those who make movies would need to exclude non-white actors from the script. In our real world, this is an unacceptable act of career genocide. Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale had a similar anomaly. In Gilead there could be no place for black women, even fertile ones. In real life, on the set, beyond the fourth wall, black actors need to work too. In The High Castle, when Juliana travels west to the mountains, we see black and brown faces in leading roles. Non-white races, Jews and gays are doomed in the Reich, or irrelevant gaijin for the Japanese, but are (temporarily) free to carve out an existence in the ungoverned poor territories.

Our appetite for dystopian narrative seems insatiable, alongside some need to bend the story to current social concerns. Now that the doom callers of climate change are raising their voices more loudly and convincingly, curiosity about how a post-catastrophic planet might look will continue to grow. However, if anyone wants to experience a Mad Max world in its grim reality, it’s possible in our present world. There’s always Somalia, where gangs vie for power in barren landscapes and battered towns, driving furiously in their “technicals” — Toyota pickup trucks with mounted machine guns. Or, a former British soldier recently told me, “Try a month in Helmand.” (The hell-hole Taliban province in Afghanistan). There also are the wastelands of Mexican provinces ravaged by sadistic drug cartels.

These dystopias are not romantic enough, however. There’s little scope for a romantic tryst in Mogadishu, where a lustful glance at a man’s sister is enough to have both lovebirds summarily executed. There’s no romance in the quotidian fear gripping these places that already exist outside of science or fantasy fiction. If any dystopian romantics fantasise about the thrills of living in bleak societies or being heroes in violent chaos, they have never seen it up close in civil-war Beirut, in Serb-oppressed Kosovo, or in the black and blasted streets of Belfast in the ‘70s. A would-be hero’s life can be painful, bloody and short in such places.

Yet, in Dick’s saga of an America conquered by Nazi Germans and imperial Japanese, we get tales of heroism from Juliana, Frank and the Black Resistance. Not to mention the lusts and loves that stalk people of action and principle — in fiction at least. In an interview, Dick once noted that his characters are all “ultimately small, ordinary believable people made big by their stamina in the face of an uncertain world.” Even villains can evoke sympathy — not Hitler or his evil cronies, but John Smith at least. By any measure, Smith is a traitor, a coward and a criminal of both war and peace. He is Benedict Arnold, (swaps his uniform for that of the enemy), Quisling (running his country for invaders), and Phillipe Petain (rounding up his citizens for Nazi death camps). We may never have swallowed the propaganda about Nazi officers who were perfect husbands and fathers with nice dogs and a taste for wine and classical music, who yet went off to work every morning in a murder factory. Yet we suspend belief for John Smith, seen at times in the Amazon series as a decent hometown Nazi who fights for his family, as well as for his rancid overlords, Himmler and Goebbels. The brave new worlds of science fiction are usually projections of the present rather than imaginings of the future.

Authors invariably reimagine the uncivilised states we know far too well as a clash of alien civilisations. Worlds created by Aldous Huxley, H.G. Wells, George Orwell and Dick are warnings of what may happen if we don’t pay attention to the world as it is now. Writers frequently reject such interpretations of their literary efforts as facile, but they sound as if they protest too much. Dystopian writing has a longer history than we might imagine — it has been around since the dawn of consciousness. Take these miserable lines of the 1st century BCE Roman poet Horace (Epode 16):

We, an unholy blood-stained age, will destroy the land

which savages will seize again.

And so, a barbarian victor will stand on the ashes

and horses will trample the city under resounding hooves.

The bones of Romulus are now hidden from the wind and sun —

but arrogance will scatter them (a visible crime).

Is there a chance the best of you

could free us from this evil fate?

There are interesting conversations to be had about the relationship between utopian and dystopian literature, one person’s quid being another one’s quo. Few of us would want to live in the utopias authors have conjured up over the ages any more than we would choose their dystopias. Plato himself would not have cared to live in his own Republic. In many cases, both types of fictional societies were satirical in nature. In those halcyon eras and areas where one could be burned at the stake or dismembered for criticising the society one lived in, fiction provided some deniability for those pointing out what idiots, hypocrites, thieves and sadists they had as leaders. Both utopian and dystopian narratives projected contemporary trends to their worst conclusions. The interlocking of utopian and dystopian visions is eerily captured in the opening credits of Amazon’s Man in the High Castle. The lovely song Edelweiss, a hymn to occupied Austria from the Sound of Music, is used with terrifying effect. It creeps across the screen like a silent nuclear bomber, its heartbreaking sweetness converted to Nazi hissing over a destroyed American homeland:

Edelweiss, Edelweiss

Every morning you greet me

Small and white, clean and bright

You look happy to meet me

Blossom of snow may you bloom and grow

Bloom and grow forever

Edelweiss, Edelweiss

Bless my homeland forever.

Small and oh so racially white. And the ghostly voice sings “blosshum of shnow,” like a killer child in a horror movie. Even the Smiths’ simple daily routines are sinister. Every morning they greet one another with cheery Sieg heils! Dad wears his Nazi regalia to breakfast in his impeccable suburban home, while his son Thomas grumbles about some uppity jerk in his Hitler Youth school.

The word utopia comes from Greek words for “not” and “place”, or no place. Sir Thomas More coined it in 1516 for his novel Utopia, from which comes our modern usage. A utopia is a non-existent society described in often excruciating detail. Dystopia, however, means “bad place” and no one has ever denied that such a thing exists and has always existed. As Dante discovered, it’s much more fun, and easier, to describe hell than heaven. When we consider utopian literature we find there are socialist, capitalist, democratic, anarchist, patriarchal, philosophical, royal, and egalitarian utopias, to select just a few random adjectives. Modern times have added left-wing, right-wing, reformist, ethnic, naturist, feminist, polygamous, gay, lesbian and many more utopias. The only question remaining is, how bad do any of these miserable utopias have to be to become a dystopia?

The rise of totalitarianism inspired a flood of dystopian novels like The Man in the High Castle and the more famous pair, Huxley’s Brave New World and Orwell’s 1984. After World War II and the later collapse of Communism, totalitarian states began to fade in dystopian fiction as authors transferred our fears to technological arrogance, environmental collapse, corporate evil, and smartass computers. But there’s nothing new under an evil star. In Dystopia: A Natural History, author Gregory Claeys cites a book published in 1892 by Samuel Crocker. In That Island: A Political Romance, “bankers exploit the working classes to a degree that is shameful and humiliating.” Really? Who on earth, then or now, could believe such a ridiculous plot? And now totalitarianism has made a tentative comeback in the streaming series of The Handmaid’s Tale and The Man in the High Castle. No prizes for guessing why; if in doubt, tune in to Fox News to watch a world going feral again.

Dystopian literature may owe more to myth and fairytale than to science. The stories really are heroes’ journeys that happen to be set in an imagined future — a concept that we see more clearly in science fiction’s young-adult cousin, fantasy fiction. There is a hero, reluctant or willing. Something happens, a messenger brings news, and the protagonist is projected into the unknown, a trek into darkness and danger, of allies and aliens. Their destiny is nothing less than to change their world. As in literary novels, the external adventures of the characters should mirror some inner emotional journey through friends, family, love, loss, and death.

A modern author of Chinese science fiction, Liu Cixin, writes about a stealthy conquest of humanity by an incomprehensively advanced trans-galactic civilisation. He is typical of those authors who deny that they are projecting their present worldview onto the future. Like other sci-fi writers, he is concerned that what he writes should be regarded as literary fiction with a skeleton of science. Philip Dick published almost exclusively in the science fiction genre of the 1950s, such as the pulp magazines. But he was obsessed with earning a reputation as a literary author. In 1960, he wrote, “I am willing to take twenty to thirty years to succeed as a literary writer.” He never made it and for the critics, he remained forever associated with rockets and ray-guns and flying saucers.

Liu has successfully achieved literary recognition in China where his trilogy, The Three-body Problem, sells in millions, and his status is godlike. Commentators have of course seen in his novels the vision of a rapidly developing “alien” China taking on a declining “civilised” west. This interpretation imagines an advanced China building on, not copying, the technical and scientific achievements of the West. Liu is not much enamoured with democracy as a means to achieve this, since China has so far progressed very well without it. The people care about their income, homes, families, vacations and modern possessions, and the state has been delivering these for recent decades.

This is a theme that traditional liberals had better get used to hearing. Authoritarianism may be the flavour of the coming decade and many dystopian creations assert that the masses will accept authoritarian rule if it delivers not a diversion of bread and circuses, but a reality of nice apartments and great technology. “China is on the path of rapid modernization and progress, kind of like the U.S. during the golden age of science fiction,” Liu said in an interview after the first volume of The Three-body Problem was published in English in 2014. “The future will be full of threats and challenges and be very fertile soil for fiction,” he said — note, “fiction,” not “science fiction.”

It’s tempting to see the dystopian gloom as new fascism, but the canned left-right labels and clichés of the 19th and 20th centuries are growing more tired and meaningless. Socialism is unlikely to add any more to its failed legacy of empty stores selling little more than wooden shelves, and its joyless bureaucrats wearing brown Bulgarian suits. And as for the other lot, with their Sieg heils, jackboots and operatic uniforms, they are unlikely to return in these old manifestations either. Something new and alien is walking among us, and we don’t yet know what it is.