by Andrea Scrima

Eve Sussman and Simon Lee are visual artists who use a variety of media, ranging from photography and film to live performance. Some of their work experiments with narrative tropes in video, text, and the act of talking to other people on the phone or in the real world. Their joint projects include CollusionNoCollusion, created during a residency in St. Petersburg, Russia; No food No money No jewels, commissioned by the Experimental Media and Performing Art Center in Troy, New York; the performance/installation Barbershop; and the live channeling performance … and all the reporters laughed and took pictures. Together they co-founded the Wallabout Oyster Theatre, a micro-theatre run out of their studios in Brooklyn. Sussman and Lee also act as producers for Jack & Leigh Ruby, two reformed criminals who are now making art and films based on their previous career as successful con artists. Recently Sussman and Lee have started working with snark.art.

Eve Sussman and Simon Lee are visual artists who use a variety of media, ranging from photography and film to live performance. Some of their work experiments with narrative tropes in video, text, and the act of talking to other people on the phone or in the real world. Their joint projects include CollusionNoCollusion, created during a residency in St. Petersburg, Russia; No food No money No jewels, commissioned by the Experimental Media and Performing Art Center in Troy, New York; the performance/installation Barbershop; and the live channeling performance … and all the reporters laughed and took pictures. Together they co-founded the Wallabout Oyster Theatre, a micro-theatre run out of their studios in Brooklyn. Sussman and Lee also act as producers for Jack & Leigh Ruby, two reformed criminals who are now making art and films based on their previous career as successful con artists. Recently Sussman and Lee have started working with snark.art.

Eve Sussman works with film, video, installation, and live performance. Her work—which ranges from small-gauge analogue film and multi-camera surveillance operations to full-blown hi-def film and video productions—has been shown in institutions and film festivals including the Reina Sofia in Madrid, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Whitney Museum in New York, the Louisiana Museum in Denmark, Whitechapel Gallery in London, the Leeum Museum in Seoul, Korea, and the Musée d’art Contemporain de Montréal. Film festivals include Sundance, Toronto International Film Festival, Berlinale, and the Moscow International Film Festival. Her live-editing algorithmic movie whiteonwhite:algorithmicnoir is in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington D.C. Sussman’s work has been supported by NYSCA, NYFA, the Guggenheim Foundation, the Jerome Foundation, and Creative Capital, among others.

Simon Lee works in photography, video, installation, and live performance. Critic Holland Cotter called his work “a powerful metaphor for the random flow of history and a low-tech formal tour de force” (New York Times). His 2010 film collaboration with Algis Kizys, Where is the Black Beast? (2010) was shown at the Sagamore Collection in Miami, Zebra Poetry Film Festival Berlin, and the IFC Center in New York, and was an official selection at the 2011 Rotterdam Film Festival. Lee has exhibited at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, the Berkshire Museum in MA, Roebling Hall in New York, the Moscow International Film Festival, the Musée d’Art Contemporain de Montreal, the Poznan Biennale in Poland, the Rotunda Gallery in Brooklyn NY, the Tinguely Museum in Basel, Switzerland, the Espace Paul Ricard in Paris, France, and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.

Andrea Scrima: I’d like to talk about the element of doubling you both use in some of your film works. Actors playing the role of prompter or souffleuse whisper the words of a text into the ears of other actors—you’ve referred to this as channeling—who then repeat them in character. Or they recite words transmitted to them in an earpiece. This doubling of text shifts the site of language to a kind of interstice: between script and enactment, the spoken and unspoken, intention and effect. I’m reminded of power structures, i.e. between manipulator and a person manipulated; someone issues orders while someone else carries them out. When did you first begin using channeling?

Simon Lee: The first time that I experienced (or thought about) channeling as a cinematic device was at a Wooster Group production of Hamlet. There came a moment in the play when the action seemed to freeze and all attention was placed on one actor speaking lines as if disconnected from the ensemble. It felt like they were speaking internally for the benefit of themselves, not outwardly projecting to the audience—seemingly breaking a theatrical tradition. And although at that point I didn’t know what was happening, I was transfixed by it—the demeanor and concentration of the actor was very compelling. It eventually dawned on me what was happening—the actor was repeating lines fed to them through an earpiece—and although I was sitting in a theater watching a play, it opened up a whole realm of cinematic possibility.

At the time, Eve and I were knocking around an idea of conflating Tarkovsky’s film Stalker with A.A. Milne’s children’s book House at Pooh Corner. It seemed to us that there were some parallels that both stories shared from different ends of a spectrum. Milne was clearly introducing his child (Christopher Robin) to the characters he would encounter as he grew up by characterizing the child’s cuddly toys into types (Pooh the poet, Rabbit the know-it-all, Eeyore the pessimist, Owl who lives in the glory of an imagined past, Piglet who just needs to hold someone’s hand as the daily adventure unfolds, and so on). Age those characters 30 years and Tarkovsky’s Scientist, Writer, Wife, and Stalker emerge.

We wrote a lot of stuff, friends of ours wrote a lot of stuff, we rehearsed and improvised with this writing, but always at the end of the day it seemed inadequate and often “off key.” The breakthrough came when we realized that there was no need to write new material because it was already out there. With the help of platforms such as YouTube, we started listening to real people telling their stories, answering questions, and making statements (from the known Richard Nixon to the unknown Stephanie Lazarus) and the obvious way to utilize this “found” script was to channel it directly to the actors through earpieces. The possibilities multiplied rapidly.

Eve Sussman: Stalkerpooh, which was re-titled No food No money No jewels, was our first instance of using channeling. As a theatrical device it allowed a fluidity that traditional forms don’t. Performers can switch roles/texts quickly, one doesn’t actually need performance chops or experience to do it. People are eager to try it as a game or challenge, even shy people without a performative bone in their body can channel.

As a scripting device channeling allowed us to improvise, combining and re-combining texts and characters with different context, cross-talk, non sequiturs, resulting in abstract random absurdities and new meaning. A text from the mime Marcel Marceau might combine with a deposed Whittaker Chambers at the House Un-American Activities Committee.

As for the concept of the souffleuse (which I had to look up)—in which one actor channels to another—that was a technique we first employed in St. Petersburg, Russia, in CollusionNoCollusion. Some of our actors were bilingual and some only spoke Russian. Our bilingual performers became “Translator-Directors” acting as both simultaneous translators—hearing English and channeling Russian—and “puppet-masters.” As well as translating the English they received in their earpieces, the “Translator-Directors” physically moved their “Partner-Performer” through the blocking necessary for each scene. This meant that every dialogue was crowded with double the number of actors it called for, the crowding at times reminiscent of a Greek chorus.

CollusionNoCollusion was sourced from episodes of Peyton Place, one of the first American TV soap operas from the 1960s.

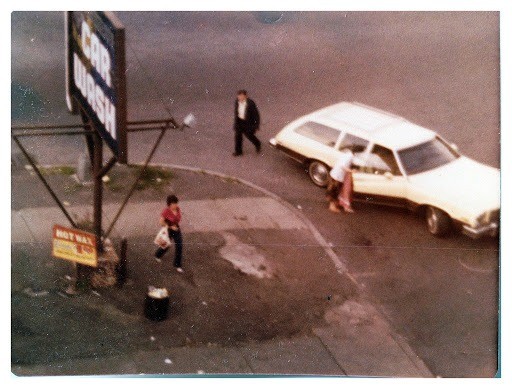

A.S.: The elements of channeling and doubling also appear in the installation Car Wash Incident you made with Jack and Leigh Ruby. There are two screens: we see people crossing a dusty street on a hot day and a station wagon cruising slowly by as a “girl in a red shirt” played by several actors comes and goes. Takes of the same scenes appear simultaneously, but with subtle differences. The off-screen dialogue sounds like a cross between crime scene (Did you give her the bag?) and a Beckettian repetition loop. Are you looking at ideas of cultural reenactment, a kind of scripting imbedded in the collective subconscious?

S.L.: The simple answer to that is “yes,” but I had no intention that this would be one of the things that became palpable in the finished piece.

We took one of the most nondescript snapshots in the history of nondescript snapshots, this one we guess circa 1973, found in Jack and Leigh Ruby’s archive of evidential material used at their trial, and began to think about it. The first thing we noticed was that everyone was in motion: the woman with the coat was exiting the car; the driver of the car (unseen in the photograph) was presumably about to drive away after they had dropped her off; the man in black was crossing the street behind the car; and the girl with the bag in the red shirt who was walking along the sidewalk parallel with the car’s presumed future direction.

Jack & Leigh’s initial invention was that all the characters were in fact connected with each other and that there was some kind of deal going down. To that end we began to characterize the protagonists in the photo. But more importantly, we decided to double them so that there would be two men in black, two girls in a red shirt, two drivers and so on. Very quickly after that we decided to double the set, placing them next to each other so that the four actors (now eight actors) could move from one set to the other—in effect moving from one world into a parallel world that contained the same protagonists but not the same actors playing them.

The choreography for this piece, the endless loop that the actors made traversing one set to the other, was engineered by the choreographer and dancer Claudia de Serpa Soares and the actor and writer Jeff Wood (who also appeared in the piece as one of the two drivers). And you are exactly right that in the Beckettian sense the actors could still be doing it now as we speak—there is no beginning, middle, or end to their odyssey with the plastic bag.

I think that I should clarify that when I make art I have no clear objective. I rely upon intuition, an excitement about an idea that has entered my head. Whenever I give reason to an idea it has always been the first tiny little death throe that indicates that I will never make that piece—my interest in it has been corrupted. To me it makes more sense to make something, however comprehensible or not to the viewer, and allow the viewer to impose their own agenda on it. It’s at that point that I believe a genuine communication starts and an artwork begins to truly do its job.

E.S.: I would call it the creation of a psychological condition, rather than a re-enactment. There is a goal to create something that looks familiar but in fact is completely off and wrong, upon closer inspection. Car Wash Incident uses the tropes of a 1970s Sunshine Noir, but in fact is a completely ridiculous endless loop, where nothing is ever resolved, so in that sense, yes, Beckettian.

A.S.: In No food, No money, No jewels, another multi-screen installation, you also use the element of doubling, but the layers of cultural criticism here seem even more pronounced. Suburbia, existentialist dread, the capitalist objectification of the worker and an American obsession with getting rich—what were the concerns driving this work?

S.L.: It’s easier for me to talk about the inspirations that drove No food, No money, No Jewels (NfNmNj) than the concerns driving the work. So maybe I can give you four little vignettes.

First: We were in Dubai filming scenes for Eve’s piece whiteonwhite:algorithmicnoir, and one day I turned a corner in Old Market and came across a beautiful and riveting scene. A bunch of young guys were shoveling sand five stories up the façade of an old building for whatever construction purpose. They’d made a bit of a wobbly-looking scaffolding with five stages to it; the guy on the ground took a shovel full of sand and pitched it to the first stage of the scaffolding, where another guy scooped it up and threw it to the second stage, where the guy on the second stage scooped it up and pitched it to the third stage, and so on up the building. Already it was a beautiful choreography, but add into it that they appeared to be costumed because all of them wore loose-fitting sand-colored tunics and work trousers and each of them had a bright orange bandana holding back their jet-black hair. In other words, they were costumed like a theatrical ensemble. With their tacit approval I made a short stop-action film of the performance.

Second: For years we passed an abandoned construction site that had a deep pit scalloped out of its center—the whole site was overgrown and strewn with rebar and concrete. It’s close to the Brooklyn side of the Williamsburg Bridge, and there is a regular stream of subway trains crossing the bridge a hundred feet above the site. One day Eve said “This would be a great place to stage Stalker” (meaning Tarkovsky’s film) and I replied “Only if we combine it with House at Pooh Corner.” We laughed, but the idea didn’t leave us; each morning the conception grew and we started calling the idea Stalkerpooh. One morning it became shockingly evident that new construction had begun on this seemingly forever abandoned wasteland, and that whatever ambitions we had for the site were foiled.

Third: I have already touched on this in a previous answer, but we began to write a script for this idea—the conflation of Stalker with Pooh. There are storyline similarities: Stalker, Writer, and Scientist set out to visit the Zone—they abandon the socialite right at the beginning; Christopher Robin, Pooh, Piglet, Rabbit, and Tigger set out to visit the Hundred Acre Wood and abandon Tigger on the way; neither party achieves their objective; Christopher Robin et al. arrive back in time for tea and Stalker et al. arrive back at the bar they set out from that morning.

Fourth: It eventually dawned on us that the script for these scenarios had already been spoken. And that’s when we began to listen to the words of Lance Armstrong, Albert Speer, Julia Childs, Jimmy Hoffa, Alger Hiss, Princess Diana, Lance Loud, Stephanie Lazarus, Marcel Marceau, Charlie Watts, Denis Thatcher, and others and channel them to the actors rehearsing and taking part in the piece.

I understand that I am not directly answering your question—what are the direct concerns driving this piece? But I am trying to give a history of how the piece came about. I’m trying to give you the peripheral, elliptical stories behind why we made NfNmNj. The guys in Dubai’s Old Market were being oppressed for less than minimum wage, they were worker immigrants from Bangladesh that lived in a work camp and sent their wages home to support their families; the construction site that Eve and I originally fantasized about producing Stalkerpooh on became luxury apartments in Williamsburg, Brooklyn; the deceits of powerful people—their spoken words—became our script; we built a useless factory that circulated water for no reason.

A.S.: How much do you allow your actors to improvise?

S.L.: It varies. During the rehearsal stage of a production we encourage a lot of improvisation driven both by the actors and by us the directors—but that would seem to be quite a normal convention within any theatrical/filmic/performance-based work. It allows the actors to find the limits of their characters and allows us to discover the limits of our concept.

When it comes to “film in the camera and rolling” or a live performance, it changes from project to project. For instance in Car Wash Incident we established a fairly rigorous choreography—each character was doubled, as was the set, and within the choreography the characters moved from one set to the other on a precise schedule. There was not a lot of room for improvisation. However, the dialogue was completely improvised by the actors on the day—and it was only one day of shooting—16 takes of the same scene from three different camera angles. We rehearsed the action once or maybe twice, it was relatively simple for each actor to be in the right place at the right time as they moved through the two sets, we gave them a suggestion of who they were and then gave them carte blanche to improvise their dialogue. I think it was the right decision because it allowed “the girl in red” for instance to start a conversation with “the mother,” cross into the other set (as the choreography demanded), and continue the conversation with a completely different actor playing the “mother” who had just had a very different conversation with the other “girl in red” from the other set. In a sense, the piece demanded improvisation from the actors.

At the other end of the spectrum, with a piece like CollusionNoCollusion, the actors were asked to be very precise with their dialogue—it was very necessary to the concept of the piece. We were channeling spoken English into the ears of simultaneous translators who were speaking it translated into Russian into the ears of the actors. Undoubtedly there was some “improvisation” going on in this scenario that we don’t even know about (neither of us being Russian speakers)—but the attempt was to achieve a kind of cacophonous Greek Chorus speaking the words of a TV soap opera in two different languages simultaneously and to show it happening with all of the tropes (set, hair, make-up, and costuming) of the original soap opera.

One other thing in terms of improvisation. At one point during the rehearsals for CollusionNoCollusion, a very good actor instinctively tightly embraced another very good actor from behind and whispered the words into his ear and the embraced (imprisoned) actor repeated them. It was a sensational improvised and real moment that I think everyone at the rehearsal recognized. I think of it now not so much in terms of your improvisation question, but more in terms of your earlier power structure puppet / master question.

Neither actor was extreme in their play. Each accepted the other and played a role without drama. The audience was the rest of us at the rehearsal. We never captured it on film. As Eve and I packed up and left St. Petersburg with our carefully archived hours of footage on duplicated hard drives, we began to realize that it didn’t matter if we lost all of it at the airport. Our best attempt at making art and the audience that experienced it, in St. Petersburg, was in the past, our hard drives were the mere documentation of something that had happened.

A.S.: Eve, you’re currently working on a dance piece titled Madison Color Theory, what does “Madison” refer to in the title?

E.S: The Madison is a social line dance from the ’50s, made famous in “Band of Outsiders” by Godard. (Purists will point to the American version of the Madison as the original, but it’s a lot less cool. I prefer the French version.)

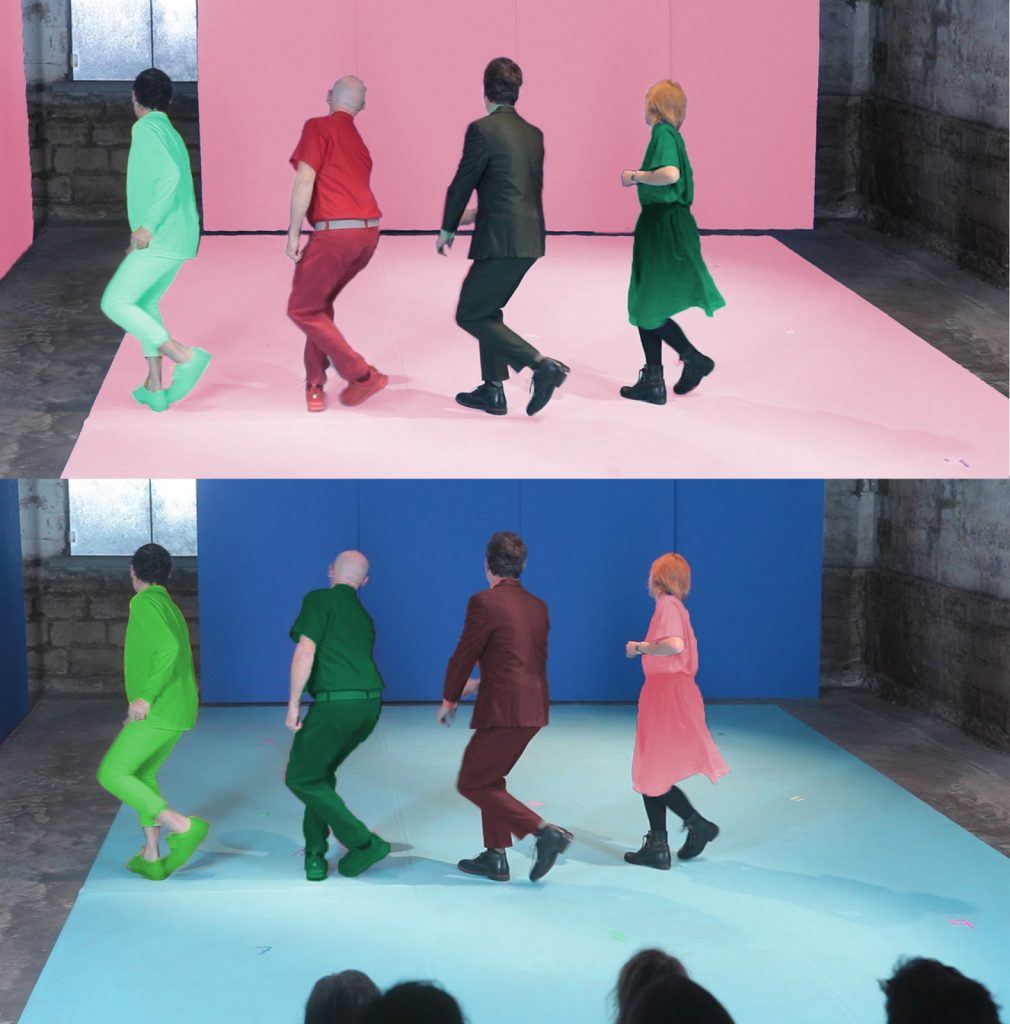

A.S.: In the piece you give the dancers instructions in real time through an earpiece—acting as a “caller.” Green enters the makeshift stage and begins a slow dance; Blue enters in synch, and then, all of a sudden, Black/White makes an appearance—who later exchanges his white shirt with a blue one, and still later dons a green suit. In a later rehearsal the entire stage switches from blue to pink. Can you talk a bit about the ideas behind the piece?

E.S.: Catharsis and joy are shared via popular social dancing. This is something that is often missing for me in contemporary dance pieces. Madison Color Theory is an exploration of formalism and the exuberant joy borne of dancing with other people. The piece combines seemingly disparate elements: a social line dance, DJ-ed sound, live “calls,” and color theory. MCT’s material is the steps of the dance, a click track that moves from 5bpm to 200bpm over the course of the show, a set and costumes that change color. Ideas about frame, color, geometry, and light—usually the realm of minimalist painting—conflate with the control the DJ/caller has over the performers. In MCT we break apart the steps and reassemble them to explore how basic, minimal elements—interaction of movement and color with specific “channeled” audio—lead to exuberance, albeit generated via the control inherent in having a “caller.”

Playing with the traditions of social dancing, Madison Color Theory uses a caller (or two), similar to our use of the souffleuse or “puppet master” in CollusionNoCollusion. My rehearsal director and I are in a soundproof booth on stage, which allows us to send audio that performers can hear but the public can only hear at specific moments. We are improvising, streaming click tracks, music, ambient sounds and spoken directions to the performers. Each performer hears their own specific track. The audience is only privy to some of this, sometimes hearing unadorned, ambient sounds (footsteps, claps, snaps, breath) without accompaniment, at other times hearing the “calls” we have invented. The piece is playing with the conflict of exuberance and control. The dance becomes a joyful act, yet the caller has ultimate control over the performers (not that they don’t occasionally revolt).

It feels more accurate to say MCT is grappling with “essentialism”—what are the most essential elements you can break a thing into? Once those blocks are decided, how can you put them back together in exciting ways? Can the simple act of yellow disappearing behind a wall and reappearing as red be surprising? Where is the cathartic moment in dance? at 160bpm? at 200bpm? If each step is its own autonomous element, how much or badly can you rearrange them, calling directions on the fly?

That geometric abstraction as it manifests in painting and the joy of social dancing, at least on the surface, have nothing to do with each other, is belied by the fact that ultimately they both can swing when you hit the right configuration of color, form, and tempo.

A.S.: Simon, I’d like to ask you about your four-channel film installation Where is the Black Beast?, based on Crow—The Life and Songs of the Crow by the poet Ted Hughes. The work is comprised of hundreds of found photographs from the early twentieth century to the seventies: faded snapshots, old family photographs of people presumably dead—grainy images that merge together to form a poetic visual narrative. Hughes’s Crow, read out loud in different voices for the audio, offers a bleak perspective on what it means to be human; the relentless narrative in turn colors the way we perceive the photographs. Suddenly, it’s the subterfuge, the evil intent in people’s eyes that emerges; the way they seem stuck in time, like a bug in a spider web; the hostile fate they’re hurtling towards: “flying the black flag of himself.” Is this the first time you’ve created a piece based on a work of literature?

S.L.: Yes, it is the first and only time that I’ve made a piece based on a work of literature. Early on, when I was a painter, I believe that my first successful paintings were based on pieces of music. Other than that I have several times titled works using literary quotes: Taken at the Flood; Things Fall Apart; Bound in Shallows; Everything that ever Happened and others.

The genesis of Where is the Black Beast? started way back in 1979 when I first recognized that Hughes’s poetry had a phenomenal visual (even cinematic) element to it:

And when the seamonster surfaced and stared at the rowboat

Somehow his eyes failed to click

And when he saw the man’s head cleft with a hatchet

Somehow staring blank swallowed his entire face

Just at the crucial moment

Then disgorged it again whole

As if nothing had happened

The first edition of Crow. The Life and Songs of the Crow has a beautiful drawing by Leonard Baskin on its cover and I discovered that this drawing was just one of many that Baskin had made of crows completely independently from Hughes’s poetry. In fact the drawings preceded the poetry and to some extent inspired Hughes to give a persona and an indelible literary and visual image to the poems. With the poems, in part, being inspired by drawings, it occurred to me that it could be interesting to use the poems as the inspiration for a film. In other words from a visual image to a literary image and then back to a visual image.

There is much to read about Hughes’s culpability in his wife’s suicide, the poet Sylvia Plath. The collection of poems that became CROW is thought to be a direct result of this family catastrophe—I have nothing to add other than that the poems exude an aura of darkness expressed in familial terms, thus the idea of juxtaposing these poems with the snapshot images from everyone’s camera began to make sense.

I had become a collector of found snapshots and although at the back of my mind there was the concept of making a film with them, it was never clear to me how to do that. One day I discovered that my friend, the musician Algis Kizys, also had a high regard for Ted Hughes and in particular The Life and Songs of the Crow. I told him of my past thoughts to make a film of the poems and we determined to collaborate and give it a shot and my collection of found snapshots became a key resource in the enterprise.

I have one other thing to add. Hughes wrote CROW circa 1967 (it was first published in 1970). There was an extraordinary cultural movement going on at that time; the shift from post-World War II aftermath to the Summer of Love.

So when Hughes was writing:

God tried to teach Crow how to talk.

‘Love,’ said God. ‘Say, Love.’

Crow gaped, and the white shark crashed into the sea

And went rolling downwards, discovering its own depth.

The Beatles were writing:

I read the news today, oh boy

4,000 holes in Blackburn, Lancashire

And though the holes were rather small

They had to count them all

Now they know how many holes it takes to fill the Albert Hall

I’d love to turn you on

It seemed to me that Hughes was embedded in a post-war, old-world paradigm, an Anglo-Christian view of the world. By 1967 Lennon and McCartney (just as an example) were part of a new poetic paradigm—free love, hippiedom— therefore the use of snapshot photographs, from as early as the 1920s up to and beyond the 1980s, seemed like it could bridge those two paradigms.

A.S.: This blending of paradigms is also evident in the test episode I viewed recently from your new work-in-progress, Looking for the Animals, made up of three-minute episodes each of which is comprised of three disconnected scenes. Letters purchased at estate sales and in thrift stores are read in voiceover; one of these is written by an attorney tasked with managing the personal effects of a recently deceased friend of the letter’s addressee, who, oddly, “never mentioned anyone named Henry.” Another letter describes a dream in which the narrator finds a large amount of cash that turns out, upon closer inspection, to be nothing more than old receipts, coupons, and worthless foreign currency: one of the bills was “from a place in a work of fiction that I had read as a child.” The third excerpt is written by a young woman who seems to be reminding her absent lover of the things he promised to give her. You’ve spoken about your ideas for turning these voices into characters and assembling them together to form a kind of “soap opera,” and it strikes me as a literary project as much as an artistic one. Are you planning to add a fictional narrative to the piece, or will the drama arise purely out of the juxtaposition of found material?

S.L.: There is already a large fictional element to the piece. The correspondence found at the thrift stores and estate sales is just a part of the narrative.

While looking for discarded snapshots I would quite often come across old letters which I would sometimes briefly read but more often than not discard as uninteresting to me. Occasionally a letter would pique my interest: the letter announcing the death of a seemingly awful relative whose ashes had been scattered in the wrong place by mistake and ending with a joke at the expense of the dead person, for example. At some point it occurred to me that I could reply to some of these letters—perhaps if there was a continuum of response a narrative might emerge. So I began to actively seek out letters and reply to the ones that interested me. I recognized however that my voice was equivalent to a monotone and what was needed was a more symphonic approach. So I started sending my replies (and sometimes original letters) to other writers for a response—and of course the palette began to expand, as did the narratives.

I liken this to a soap opera because there is no beginning, middle, or end to it. If I were to turn on the TV and watch the 169th episode of a soap opera I had never seen before, I would be engaged, like everybody else, for perhaps twenty minutes with no need to know the provenance of the characters or the story—I would be jumping into the middle of the narrative. It seems to me that taking a randomly found letter is the equivalent of jumping into the middle of an unknown history and by replying to it I (and the other writers) begin to influence its direction—and that can be exhilarating and inventive as much as it may produce tiresome doggerel.

A.S.: Again, we have narratives of money: the furs (and animals!) in the deceased man’s estate, the dream of striking it rich that’s quickly dashed, the young woman’s appeal: “You say you buy these things for me—where are they?”

S.L.: Perhaps the subject matter comes from the original letters. I collect letters from wherever I go and have them translated into English when necessary—so the collection to date is limited in the sense that there are many places I have not been. But aligned to that is that I have replied to letters written almost a hundred years ago. So the cultural span is limited to my travels, but the temporal span is quite wide. All this to say that a consistent theme within the letters is the struggle for survival.

With the thought that it may be interesting to examine that, I’ll break down the three examples you’ve cited. The origin of the story about the furs (referenced as “the animals” by one of the project writers) comes from East Germany circa the early 1960s. The writer is hunting foxes and selling the pelts as a way of augmenting his income—the letter seems to be to a friend who has escaped to the West, where perhaps fox pelts have a more lucrative market value than in the East. The dream of striking it rich comes from a young man forced to work in a lumber mill in Poland with inadequate clothing against the cold. The young girl’s challenge to her boyfriend about the gifts he promises but never delivers comes from Portugal in the early 1970s. Reading between the lines, she has clearly surrendered her virginity to him: I have to tell you how difficult it is for me not to confess—I have not in all these months . . . soon my Mother will notice . . . I exit the church quickly . . . So this is not about the accumulation of worldly goods. It is about pecuniary survival (the fox pelts), physical survival at the sawmill, and the emotional survival of the young girl who needs the tokens of love that will reassure her that she has made the right decision.

***

Author’s note:

This conversation is part of a series I’ve done over the past year and a half as a columnist for 3 Quarks Daily. I’ve talked to Madeleine LaRue about the Swiss writer Peter Bichsel; Liesl Schillinger about literature and politics; and Saskia Vogel about sex, pornography, and her debut novel Permission. There’s a conversation with Myriam Naumann that explores the connecting points between my book A Lesser Day and an installation I exhibited at the Berlin gallery Manière Noire, titled “The Ethnic Chinese Millionaire.” There are also conversations with the artists David Krippendorff, Alyssa DeLuccia, and others, including Joan Giroux.

The series can be found in its entirety here.