by Tim Sommers

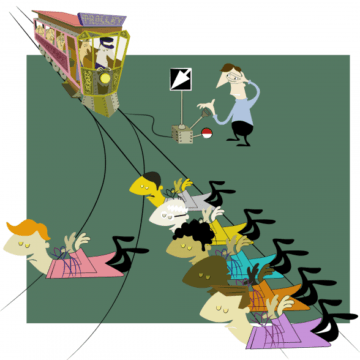

The first part of the original trolley problem goes like this. A runaway trolley is careening towards five people tied to the tracks. There’s a lever in front of you that could divert it onto a second set of tracks. Unfortunately, there is also a person tied to those tracks. You can either do nothing and let five people die or throw the switch and kill one person – but save the five. What do you do?

The first part of the original trolley problem goes like this. A runaway trolley is careening towards five people tied to the tracks. There’s a lever in front of you that could divert it onto a second set of tracks. Unfortunately, there is also a person tied to those tracks. You can either do nothing and let five people die or throw the switch and kill one person – but save the five. What do you do?

The modern version of the trolley problem goes back to the 1960s, but there are variations that go back over 100 years. The trolley problem has been featured in video games, movies, tv shows, and has been a monster meme on the internet since at least 2016. MIT has a moral machine that does nothing all day and night but ask people questions based on the trolley problem – including variations suggested by users themselves. The trolley problem has been central to debates about how to program self-driving cars and “experimental” philosophers have spent a lot of time putting people in eMRI machines and asking them the trolley problem. But many other important trolley problems have not been fully explored. Here are just a few.

Sorites’ Trolley Problem

There’s no lever but the people tied to the tracks are pretty far away. Luckily, you have a wrench and can remove one piece of the trolley at a time. How many pieces do you have to remove for it to cease being a trolley? Which piece is the one piece that once removed will mean that the trolley is no longer a trolley?

Theseus’ Trolley Problem

Rather than simply removing pieces, you swap them out one at a time with brand-new, identical pieces. If you swapped them all out before the trolley hit anyone, would it still the same trolley? Read more »

How should people on the ‘progressive’ side of politics view patriotism? That question continues to vex those who would connect with what they suppose are the feelings of the bulk of the population. The answer will vary a good deal according to which country we are considering – the French left, for instance, has a very different relationship to la patrie to that of the US or the UK. In the case of the former, the side cast as traitors has historically been seen as the right. In the USA, at least in the second half of the 20th century it has been very different: those who protested against the Vietnam war were cast as the anti patriots. And today, we still hear that the left ‘hates our country’. The accusation is a damaging one, and has been wielded with glee by conservatives whenever they have the chance. So there is a tricky task for the left, it seems: to be seen as with and not against the mass of people in their identification with the nation and its history, without abandoning an internationalist perspective that rises above the narrow nationalism of the conservative.

How should people on the ‘progressive’ side of politics view patriotism? That question continues to vex those who would connect with what they suppose are the feelings of the bulk of the population. The answer will vary a good deal according to which country we are considering – the French left, for instance, has a very different relationship to la patrie to that of the US or the UK. In the case of the former, the side cast as traitors has historically been seen as the right. In the USA, at least in the second half of the 20th century it has been very different: those who protested against the Vietnam war were cast as the anti patriots. And today, we still hear that the left ‘hates our country’. The accusation is a damaging one, and has been wielded with glee by conservatives whenever they have the chance. So there is a tricky task for the left, it seems: to be seen as with and not against the mass of people in their identification with the nation and its history, without abandoning an internationalist perspective that rises above the narrow nationalism of the conservative.

Talking about “The Enlightenment”, when understood as something like “an intellectual and philosophical movement that dominated the world of ideas in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries” (thanks,

Talking about “The Enlightenment”, when understood as something like “an intellectual and philosophical movement that dominated the world of ideas in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries” (thanks,

Sughra Raza. Untitled, April 2021.

Sughra Raza. Untitled, April 2021.

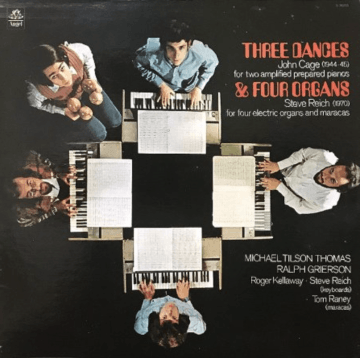

car when driving alone. Yet my momentary career as a musical performer—exceedingly brief as it may have been—enjoyed a spotlight rarely offered to others.

car when driving alone. Yet my momentary career as a musical performer—exceedingly brief as it may have been—enjoyed a spotlight rarely offered to others.