by Thomas O’Dwyer

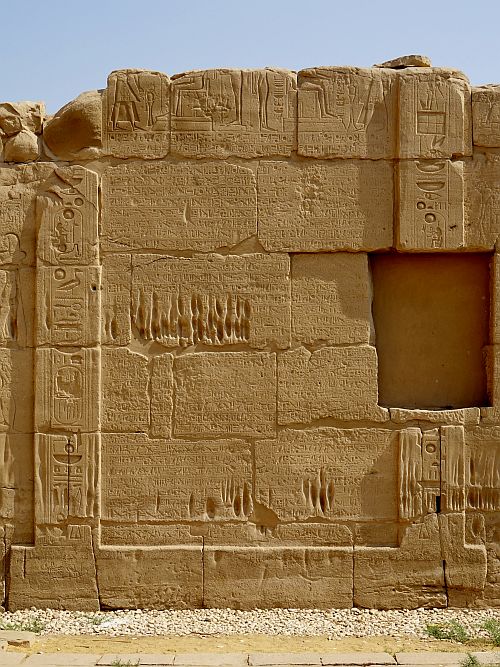

Complicated international agreements on managing the planet’s many human and natural resources may seem essentially modern, a consequence of the interdependence between nations that has been growing since the 19th century. Such accords are as necessary as sewage pipes that underpin healthy societies and just as boring. However, we possess copies of the first known international agreement signed in human affairs — and it is 3,300 years old. This treaty for peace and economic cooperation ended conflicts between the Egyptian and Hittite empires. Archaeologists found a copy of the treaty from each side, one in Egyptian hieroglyphics in 1828 and the other in Hittite cuneiform text in 1908. The treaty itself, signed by Pharaoh Ramses II and King Hattusilis, became a model of endurance in the fractious Middle East of the 13th century BCE (plus ça change). The formerly warring states remained friends and allies for nearly 100 years until Assyria invaded and destroyed the Hittite kingdom.

And now we move from possibly the first international agreement in human history to maybe the last — if it doesn’t work, and fast. In November, Scotland will host the most prominent international conference ever seen in Britain, a memorable event with an eminently forgettable title, the 26th Conference of the Parties — COP26. (The United Nations is well known for the tedium of its terminology). A conference of the parties is the supreme governing body of any international convention and includes representatives of all the states involved plus any observers. In UN-speak, a COP aims “to review the implementation of the convention and any other legal instruments that the COP adopts.” The COP descending on Glasgow in six months has the task of saving humanity, no less, for it has to advance the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. Most will have been unaware that this conference of the parties has met (almost) every year since the first in 1995 in Berlin. The “parties” are 197 states and territories that signed on to the Climate Change Convention. And what, you may well ask, have these vast gatherings of blathering heads achieved since 1995? The answer, in good British slang, would be “Bugger all!”

That was true perhaps up to the 21st session, COP21, which sat in Paris in December 2015 and grabbed some long-overdue attention and a catchy title by drafting the first international climate agreement — The Paris Accord. It set a single scientific aim to limit global climate change to 2°C above pre-industrial levels. Member states would take relevant political and economic actions to make this happen. They said. And yet, as COP25 loomed in Madrid in 2019, experts and science reporters around the globe were warning that 2020 would draw a line under humanity’s “last chance” to do something, anything, about climate change. Global greenhouse gas emissions had risen to an all-time high, and no big states were meeting their obligations under the Paris Agreement. Indeed, one of the biggest, the United States had reneged on the agreement and stomped off into the fog of its polluted air, burning forests and political gasbags. UN Secretary-General António Guterres said: “I am more determined than ever to work for 2020 to be the year in which all countries commit to doing what science tells us is necessary.”

What we didn’t know then is that while António was preaching to an empty choir-stall, 2020 was making other plans for having us “commit to doing what science tells us is necessary.” Bye, bye, Climate Change; hello Global Pandemic. “The conference of the parties has met (almost) every year since 1995,” and 2020 was the year it didn’t. The knock-on effect from the Covid-19 pandemic for climate change is likely to be enormous. Although the world’s attention to climate has been on hold for more than a year, the issue will come roaring back to the headlines and not in a good way. The extent of humanity’s astonishing disregard for the health of the only habitable planet in the solar system had been laid bare. The pandemic that everyone knew was coming (President Barack Obama accurately predicted it in 2015) arrived, and everyone was surprised and shocked. Even the scientists scrambled and argued to establish what we needed to do, and the tragic consequences of the virus deniers’ lies were laid bare in the United States and Brazil.

As the coronavirus now heads reluctantly for the exit, it might well mutter the warning of Louis XV, “Après Moi, le déluge. You’re on, Climate Change.” The world is left shaken by the reminder of life’s fragility we have just endured. The question is, has it also learned that denying the sciences is a road to catastrophe? We should be alarmed by the advancing changes in the fragile atmosphere that keeps all living things alive. We should be doubly alarmed by the power of the merchants of death among us — the polluters, vulture capitalists, fake-news vendors, science deniers, and makers of lies. We recall the once unbelievable stories about tobacco manufacturers faking science and hiding evidence about their killer products and other industries fighting with bared claws to deny they were poisoning the environment with lead.

We know for sure the same powerful guardians of greed have been undermining the climate-action efforts. Oil companies knew all about climate change back in the 1980s. (Like big tobacco and many other “bigs”, they have no shortage of spineless scientists willing to bury uncomfortable truths in basement filing cabinets). On top of that, they have the large sums needed to construct mountains of disinformation and feed the pockets of lobbyists and useful idiots in the world’s parliaments. Why else have all those annual UN climate conferences since 1995 added nothing but more hot air to an overheating planet?

At COP25 in Madrid, the young activist Greta Thunberg scornfully savaged the delegates, saying: “Finding solutions is what COP should be all about. But it seems to have turned into some opportunity for countries to negotiate loopholes and to avoid raising their ambitions.” So what can we expect from COP26 in Glasgow, given that two years and a pandemic scare have hopefully sharpened minds since Thunberg spoke? It’s hard to see how this cannot become the most significant news event of the year. Around the world, climate activists are growing in numbers, and they are hopping mad at the criminal neglect and downright chicanery of the many establishments with vested interests in killing the climate-action debate. There are signs that a massive protest movement will descend on Glasgow; some organisers are predicting that several hundred thousand activists will show up. More than 30,000 official delegates, including heads of state, climate experts, and campaign organisations, are expected.

The Glasgow venue will have two zones, an inner Blue Zone and an outer Green Zone. The Blue Zone will be within a tight security ring, and only heads of state, ministers, and accredited officials, individuals, and organisations will have access. It is within the Blue Zone that serious international negotiations on climate change actions will take place. In the Blue Zone, each delegation has a pavilion to showcase what they are doing on climate change. Cynics have already asked where they will display what they are not doing — a seriously more important concern. Within the pavilions, countries will host programmes of exhibitions, receptions, and presentations. The UN also hosts official fringe events within the Blue Zone, which is fiercely competitive. Only one in three organisations that apply get in.

In the Green Zone, organisations that can secure space and afford it will have their pavilions with events to publicise their climate change activities. None of this is “official”, but there is an official Green Zone programme, and this zone will attract intense interest from the global media. Beyond the Green Zone, there will be unofficial programmes across Glasgow city, being prepared by many organisations and individuals. It is outside the Green Zone that we can expect to see massive protests. There is some trepidation among police and others organising security for COP26. Tensions have been rising in the UK and elsewhere amid accusations that governments are attempting to criminalise peaceful climate-action protests.

More than 400 experts, including 14 authors from the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), recently warned that governments worldwide are criminalising non-violent protesters at a critical time in the escalating climate emergency. In an open letter at the end of April, the experts wrote: “We, the undersigned, urge all governments, courts and legislative bodies around the world to halt and reverse attempts to criminalise non-violent climate protest.” The letter, signed by 429 scientists, professors and academics from 32 countries, stated:

Around the world today, those who put their voices and bodies on the line to raise the alarm are being threatened and silenced by the very countries they seek to protect. We are gravely concerned about the increasing criminalisation and targeting of climate protestors around the world. Beyond the draconian Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill that seeks to criminalise non-violent protest in the United Kingdom, worrying developments elsewhere include new laws in multiple US states that threaten non-violent protestors with lengthy prison sentences, a new Terror Law proposed in the Philippines, which would threaten climate activists, laws against protestors in France, the arrest and imprisonment of climate strikers such as Disha Ravi in India, and fossil fuel corporations directly targeting environmental rights lawyer Steve Donziger in the United States, Andy Gheorghiu in Canada and many others globally.

In the UK, more than 2,000 people who took part in recent protests by the climate-action movement Extinction Rebellion are being rolled through courts in what media reports say is one of the biggest crackdowns on demonstrations in British legal history. Dr Oscar Berglund, from the Cabot Institute for the Environment at the University of Bristol, who helped coordinate the open letter, told The Guardian that criminalising climate protest was central to the fossil fuel industry’s new strategy of delaying action on climate change. “Now that climate change denialism is in steep decline, they have put their money behind efforts to stifle dissent. Climate scientists, who have been subject to the slander of the fossil fuel lobby for so long, recognise this change in strategy,” he told the newspaper.

Many reporters on the climate-change beat in Europe sense growing anger across the continent on what activists see as arrogant collusion between big governments and big capital to keep playing down the now obvious threat to the planet and its ecosystem. The world-renowned naturalist and broadcaster Sir David Attenborough recently called on world leaders to protect nature. Addressing a virtual United Nations event, he said world leaders had a chance to make a difference. Attenborough is best known for the BBC’s natural history documentary series forming the Life collection that is a comprehensive survey of animal and plant life on Earth.

In his most recent documentary, Sir David issued a stark warning about the extinction crisis and its effects. “If ever we needed a strong signal from world leaders, for people like you, that we are going to solve this, then this is now,” he told the UN delegates. Last year, a UN report found that around one million species now face extinction. Hunting, habitat destruction and other human activities have forced many animals to the edge of oblivion. Human encroachment on the habitats of wild animals also increases the risk of outbreaks of new diseases, perhaps worse than Covid-19.

The COP26 meeting is sure to be historic, perhaps even more important than the Paris Agreement conference, especially since the United States is back on board with the urgency of the climate problem. However, it is hard not to feel a sense of gloom rolling towards Glasgow. There are worries over the possible size of the planned protests and fears over how they might escalate if the gathered leaders continue with their dithering, divisions and inaction. Most of the world’s biggest states now have goals of reaching net-zero emissions by mid-century. Few have any policies in place to meet those goals.

In April, the Cambridge Sustainability Commission on Scaling Behaviour Change called on policymakers to target the polluter elite to persuade them to shift to more sustainable behaviour. The report highlights that the responsibility for everyone to play a part in saving the planet is not evenly shared. The Cambridge Commission found that between 1990 and 2015, nearly half of the growth in global emissions was due to the wealthiest 10 percent, with the super-rich 5 percent contributing close to 40 percent. The report argued that governments must address the overconsumption of the rich. The analysis showed that emissions from the poorest half of the European Union population fell by 24 percent from 1990 to 2015. The carbon emissions from the most affluent ten percent of EU citizens grew by 3 percent, and emissions from the wealthiest one percent increased by 5 percent. This issue is made worse everywhere by the political power and influence these groups exercise on government policies.

Then there are the historic pollutants. Recent industry figures show that global use of coal was four percent higher in the last quarter of 2020 than in the same period in 2019. Here is a stark indication of a disastrous rebound in using the dirtiest fossil fuels. Global emissions were higher in December 2020 than in the previous year. An economic rebound will see emissions significantly increase in 2021. The urgent goal of reaching net-zero seems only to recede. If governments do not persuade investors that they will only lose money by investing in dirty energy, nothing will change, except our weather and atmosphere.

If you thought wearing face masks has been a pain, try to imagine wearing a full face mask linked to a portable oxygen tank. You can stroll through the gathering afternoon darkness and enjoy the spectacle of nature dying all around you. You can listen to the silence of the birds.