by Charlie Huenemann

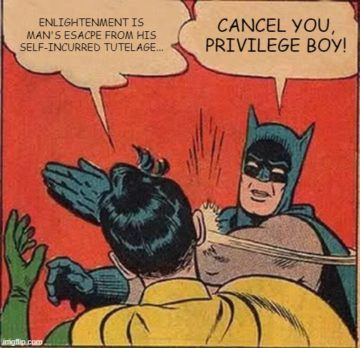

Talking about “The Enlightenment”, when understood as something like “an intellectual and philosophical movement that dominated the world of ideas in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries” (thanks, Wikipedia), is like talking about Batman: do you mean classically heroic comic Batman? or the delightfully campy Adam West Batman? or the Batman of the movies, or of the gloomy Dark Knight era? The Batman one selects will determine what further questions need to be settled, and what scales of evaluation should be used.

Talking about “The Enlightenment”, when understood as something like “an intellectual and philosophical movement that dominated the world of ideas in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries” (thanks, Wikipedia), is like talking about Batman: do you mean classically heroic comic Batman? or the delightfully campy Adam West Batman? or the Batman of the movies, or of the gloomy Dark Knight era? The Batman one selects will determine what further questions need to be settled, and what scales of evaluation should be used.

Similarly, the Enlightenment can be seen as a cluster of philosophical values (placed upon individual liberty, human equality, political and scientific progress, and independence from religion), or the ways in which those values helped to form economic institutions (slavery of various forms, global capitalism, and free markets), or as a stand-in term for whatever deep injustice people think has become dominant over the last three centuries (global economic inequalities, political states favoring the wealthy, and enduring white privilege). It is often thought that the Enlightenment is somehow a single thing behind all these things, in the way some of us think there can be a steady “Batman” character behind his various depths and flavors.

These various flavors of “Enlightenment” are not wholly disconnected. For example, John Locke formulated a system of rights, contracts, and obligations that justified slavery on at least some occasions. The notion of actual human equality was interpreted by colonizers to mean potential human equality, which licensed the brutal process of more civilized nations forcing benighted savages into “more advanced conditions”. Scientific progress seemed to demand that we regard the natural world as a resource to be controlled and consumed, and soon our air became unbreathable. Freedom from religion came to mean that the only considerations that belong in the public sphere are measurements of material loss and gain; so “sin” and “virtue” need not apply.

And so, the criticism goes, the core ideals of Enlightenment lead to an alien and inhuman operating system that maximizes material well being for some, while annihilating any local traditions and values that are not readily uploaded into the system.

Now we might wonder whether such a criticism is completely fair. Steven Pinker argued in Enlightenment Now (2018) that in every measurable respect, the ideals of the Enlightenment have done more to improve human ideas than anything else we can name. Slavery was not born of the Enlightenment; it is as old as history itself. But the ideals of the Enlightenment eventually brought about slavery’s demise (at least in its legal forms). More people have more education than ever before, and more people have moved out of poverty than ever before, and more people have more political rights and opportunities than ever before. Science has led to enormous reductions in death due to famine and disease, and has allowed us to have greater and healthier populations — though if we credit science with these boons, we should also admit that it has enabled the current climate crisis; it is hard to deny that, even as science now presents our only ways out of this crisis.

Trying to answer a simple and telling question lends very strong support to Pinker’s thesis: “When would you choose to live if you didn’t know who you would be?” The safest answer is pretty clearly: “Now.” Selecting any other age offers a significantly higher risk that you will be enslaved, subjugated, murdered, starving, sick, or illiterate.

A further observation is that the old ways of interpreting and applying the ideals of the Enlightenment are not the only ways. We might believe instead that all human beings, as they are, have a full set of rights that demand our respect, and that they should have as much autonomy over their lives as possible. We might believe that political and scientific progress should not be dedicated to capitalistic profit, and that lives of people and ecosystems should come first. We might decide to listen for the values coming from religious traditions that resonate with all of us, and accord them respect if not worship. We can become better stewards of Enlightenment ideals. If the general vibe of the Enlightenment is supposed to be one of emancipation, then perhaps the most Enlightenment thing for us to do is to emancipate ourselves from the traditions of Enlightenment, and — this time — get it right.

***

For, really, what other options are there? Give up on equality and the right of people to control their own lives? Forget about scientific progress, or using our best empirical knowledge to reform political institutions? Trust in some religion to lead the way? These options all lead in the wrong direction. We can build out from Enlightenment ideals — adding further values, or limits, or specifications to them — but there is no going back on them.

One sobering lesson we should learn from old-style Enlightenment is to have greater respect for the forms of life different from our own. While many thinkers have believed there is but one road to Enlightenment, we can realize the value and significance of the many ways humans have of getting along. We might think in Darwinian terms of how different species adapt to local environments: each human culture finds a way of being in the world that makes sense, given local constraints. This does not make it impossible for cultures to improve — for, unlike species, cultures can lift good ideas from one another. The on-going, difficult dialectic between keeping one’s traditions and learning new and better practices from other cultures is also one that is best managed at a local level, as the people most directly involved are the ones best suited to find the way forward. There will always be conflicts and losses; but that is the nature of time.

Another lesson is to not let science restrict our values. Science, as we know it, is essentially reductive and quantitative, as scientists try to develop models of the world devoid of human prejudices. Its success is undeniable. But, obviously, just because science does not have a handle on some set of human concerns does not mean they have no merit. Recently, when scientists wanted to build a 30-meter telescope on Mauna Loa in Hawaii, they had to confront the fact that to some people, that land had a wildly different sort of value than as real estate for star-gazing. Local officials made the right move in allowing for a period of dialogue and communication among the interested communities. In the end, the building permit was approved; and regardless of whether we believe that to have been the right outcome, we can endorse the general idea of putting the values of scientific discovery into open dialogue with values coming from very different sources.

A third is to broaden the ranks of experts. The Enlightenment held that knowledge is the way forward, and experts should be in charge. It was no coincidence that those experts tended to be members of the most powerful classes in society. In an age now where — thanks to the Enlightenment — we have broader access to public education than ever before, and the world’s information at our fingertips, the class of experts needs to have more permeable borders. University degrees have been handy markers of who has expertise and who does not, but it is perhaps time to rethink this use of universities. The landscape of knowledge has shifted dramatically since the founding of the University of Bologna in 1088, but the shifts in academic curricula have not kept pace. What enables a person to have relevant expertise, and to be able to make significant contributions to a discussion, needs to be reconsidered from the ground up. It may be that — heavens above! — the very idea of the university needs to be rethought.

Finally, we must learn to rediscover the Enlightenment virtue of taking pleasure in conversation. The Enlightenment, of course, was not a single school of thought, but a republic of heady chatter, with people arguing with one another over broad ranges of important ideas. We tend to shoot tweets at one another. The challenges we face are bigger than those they faced, and we need to be able to engage fruitfully and honestly with each other’s visions, ideas, and strategies. We have very few opportunities for this in the popular sphere; the promise of the web remains unfulfilled. What’s called for is a massive push in the direction of civic dialogue with an emphasis on listening, fairness, responsiveness to arguments and evidence, and the dignity in being able to change one’s mind.