by Chris Horner

How should people on the ‘progressive’ side of politics view patriotism? That question continues to vex those who would connect with what they suppose are the feelings of the bulk of the population. The answer will vary a good deal according to which country we are considering – the French left, for instance, has a very different relationship to la patrie to that of the US or the UK. In the case of the former, the side cast as traitors has historically been seen as the right. In the USA, at least in the second half of the 20th century it has been very different: those who protested against the Vietnam war were cast as the anti patriots. And today, we still hear that the left ‘hates our country’. The accusation is a damaging one, and has been wielded with glee by conservatives whenever they have the chance. So there is a tricky task for the left, it seems: to be seen as with and not against the mass of people in their identification with the nation and its history, without abandoning an internationalist perspective that rises above the narrow nationalism of the conservative.

How should people on the ‘progressive’ side of politics view patriotism? That question continues to vex those who would connect with what they suppose are the feelings of the bulk of the population. The answer will vary a good deal according to which country we are considering – the French left, for instance, has a very different relationship to la patrie to that of the US or the UK. In the case of the former, the side cast as traitors has historically been seen as the right. In the USA, at least in the second half of the 20th century it has been very different: those who protested against the Vietnam war were cast as the anti patriots. And today, we still hear that the left ‘hates our country’. The accusation is a damaging one, and has been wielded with glee by conservatives whenever they have the chance. So there is a tricky task for the left, it seems: to be seen as with and not against the mass of people in their identification with the nation and its history, without abandoning an internationalist perspective that rises above the narrow nationalism of the conservative.

I want to suggest here that we need to see that there is a problem with both the approach that seeks to inhabit the abstraction of simplistic universalism and the one that would rush into the warm embrace of parochial particularism (‘my country, right or wrong’ at its extreme). Instead, we need to see that the universal is something emergent, in and through the particular struggles and questions with which we are confronted. It is a concrete universal.

The leftist who only wants to point out the crimes and iniquities of her country, as if that would somehow win over people to a better, properly internationalist position engages in an exercise in futility. At its extreme it is the ‘no borders’ approach which castigates anyone who seems to express an attachment and loyalty to the traditions and achievements of the imagined community that people call their country. Imagined it may be, but there are real and material facts that underly the way people have experienced history, and these cannot be just wished away. And imagination is a powerful thing. Most people experience their reality as being bound up with something they call their country. Attack that as simply a lie or an evil and you will be seen as attacking the people themselves, with predictable results. This takes us nowhere, and simply plays into the hands of those who would characterise the left as the ‘enemies within’ who ‘hate their country’.

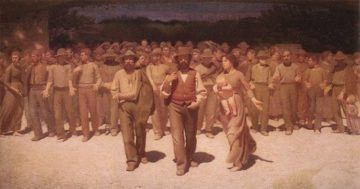

Then there is the other route: sometimes known as ‘progressive patriotism’. The idea is to show that one identifies strongly with the nation, moving in a direction that disarms accusations of disloyalty and places oneself in the warm stream of popular feeling. Again, the dangers are obvious. It is all too easy to slide into an uncritical acceptance of ‘Our National Story’ or to look like an inauthentic poseur, wrapping oneself in the flag and holding a populist pint of beer. But there are other approaches, not all of them so flat footed. One is of highlighting the positive, progressive things that have happened in the history of the nation which one can be feel authentically proud. Heroes and battles are recalled. The people who fought for the vote, the Levellers in England, the revolutionaries and campaigners against slavery.

One problem here is that of affective resonance: people can’t thrill to a story they don’t know exists. So the stories need to be retold before the point can be made. I take it that a part of the projects of EP Thompson, Howard Zinn and Peter Linebaugh is just this: to allow the submerged stories to resurface. This is valuable and important, but it takes time to reach the wider population beyond the left, if it ever does. Typically, that part of the centre left that has its eyes on electoral success is tempted to affirm the moments in history that everyone thinks they know already. These are typically cast as victories against foreign foes, especially those in World War 2: Pearl Harbor, Battle of Britain, D Day etc (it was, after all, a war against fascism). At this point whatever argument was being made about a progressive take on the nation and what it is can get lost. We bow our heads on Remembrance Day. We are all glad Hitler was defeated and most people admire the men and women who accomplished it; we forget the problematic histories of the empires that accomplished it

We get into even greater trouble when centre left parties interpret the left-patriotism move as one of putting out more flags: talking up British or American values of tolerance, liberty and fair play (as if, say, the Dutch and Canadians lacked them). The centre left party that takes this route can quickly lose its way. In recent history this has also been associated with left/centre parties adopting a conservative social policy that demonises immigrants, encourages militarised policing, a punitive criminal code and a war on benefits recipients. All in the name of being with the people and winning elections. But the right can always out do the left here. ‘Triangulating’ rightwards can leave you without an identity that anyone can see as different from the opposition, which then encourages the ‘they are all the same’ response in the electorate. And it can look like what it often is: inauthentic cosplay with flags. Moreover, the right will always have more and bigger flags to wave: a culture war over who is the more patriotic is something the right loves and usually wins.

There is no easy answer to all this, and I am not pretending to have one. But I do want to make a few suggestions. The International-at-all-costs and screw the locals line is obviously distasteful and useless. This includes the version of the progressive neoliberals of the centre left: the Clintons, the Blairs and so on. They stripped the job security from those they were supposed to represent in the name of globalisation, and then lectured the locals on the importance of retraining for jobs that had gone abroad to cheaper labour markets. Then they launched wars of choice in the name of international human rights. One can sort of see the appeal of a Trump or a Brexit party after all that. But even the saner iterations of the internationalist approach are problematic. They takes the universal (all humanity?) As the Good Thing. The trouble is that no-one is at home in the Abstract Universal. No one is just a human: we are all also people who live in particular places with specific aims and issues.

The opposite problem haunts the left patriot. This is because s/he is lauding the particular over the universal. This rarely ends well, for the reasons we have discussed. The right loves the particular; the national community, the volksgemeinschaft, Our Boys in Uniform, Our Flag – and the dangerous or toxic others outside or within the national body that must be eliminated. So it’s a dangerous game for the left to play. The particular gets homogenised into a national community, a thing ‘we have’ and they don’t: this is effectively the USP of the Right and the left goes there at its peril. At its worst, it steals the clothes of the right and gets to look and sound as parochial and xenophobic as they are. So what’s to do?

There is no easy answer, no answer that is easy and right. But here are a few thoughts. First, we must remember that a nation, a people, a citizenry isn’t identical with the national state: a population will be found to be diverse and anything but at one with itself. And the state isn’t politically neutral container into which one can pour whatever one likes: it represents class interests, and furthers those interests by propagating myths about itself to the people it rules. These have to be contested, not acquiesced in.

Second, it isn’t sealed off from the rest of the world – its history and its present is utterly entangled with that of others, particularly its neighbours – and a lot of the ‘outside’ is ‘in here’ and vice versa. The modern population is a polyglot and multi coloured thing. We are them. Part of the problem with the liberal left is that it takes as its starting point a fantasy about the people it aims to win over. We and they need to stop imagining a mono culture of hardworking, male, white men who don’t like foreigners and who do or did industrial work. The working class includes delivery drivers, waiters, cleaners and much more, women, young precarious workers, people of colour – this is the new working class and it is not always to be found in the places it once inhabited. And are these people, whether old or new working class, all socially conservative and chauvinistic? All the polls suggest this is a vast and patronising oversimplification. Of course, a part of population is inclined to to be conservative. But if we want to develop a strategy that is authentically left and progressive and has a chance of resonating with others we have to stop relying focus groups to tell the left what to say, as just repeating received opinion merely hardens the thing you want to change. A vision of a transformative project, one that really offers something improve the material conditions of the 99% is what has a chance. Not more of the same.

The events and traditions that have their roots deep in the national history and which are also worth invoking are national and international. They have often been when a sense that what is right, what we stand for, also applies to ‘them’. That they are like us, when we struggle with and for each other. Some of that will be more immediately relevant to the home population: for example: letting thousands of one’s fellow citizens die of coronavirus is unpatriotic and the left could make that point with some force. And the best of our past ought to inform our present: like the English Levellers in 1649 who went to the ports to try to persuade Cromwell’s men not to invade Ireland; the International Brigades in 1936-9 who fought fascism; Sophie Scholl defying Nazi Germany; the anti Vietnam war activists; the dead of Kent State University; the anti Iraq War protests. And there is the noble example of the Scottish workers who not only refused to work on war planes due to be sent to Pinochet’s fascist regime in Chile, but blocked their removal. These people all stood for what was best in their own traditions that also transcended the merely local. This is forging a concrete universal, one that emerges from and in the actions of people in and across borders. Plenty of examples lie before us right now. It would be good, for instance, to see our countries act on their rhetoric of freedom and rights, to do something to help the Palestinians save their land, their rights and their dignity. And if our leaders will not do it, then we must show them we do not accept their inaction. Now that’s what I’d call patriotism.