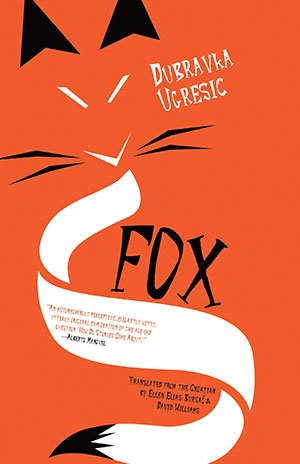

by David Oates

Small poetry presses are the gold dust of the publishing world, glittering yet easy to miss. And of enduring cumulative value.

Small poetry presses are the gold dust of the publishing world, glittering yet easy to miss. And of enduring cumulative value.

Of course the Big Five publishers will pick up suitably salable, already-famous, sure-thing poets. Penguin Random House publishes Terrance Hayes, and that’s a damn good thing, a Black poet of subtlety and immediacy; and Amanda Gorman, poet of the recent presidential inauguration; and Mary Oliver, who straddles the line between “accessible” and serious with an uncanny ease and a following most working poets cannot even imagine.

Meanwhile, as my previous essay here at 3QD proposed, the small presses do the nearly-invisible work of finding and developing new poets, and giving mid-career poets their next book or two, and taking risks with weird and strange and occasionally awful poets too. They do this the way ants collect morsels in the woods: because it is their nature.

(Fans of mixed metaphors may ask: So, are these ants collecting gold dust? And I reply: They are.)

In this essay, three books from contemporary poets whose work I admire. I read them to refresh my sense of the glorious possibilities of language. And to feel that while our public discourse may be as vicious as ever – perhaps even a little worse than the (miserable) average – yet in these small books from small presses, language may be transformative, life-giving, full of surprise and truth and therefore, hope. Read more »

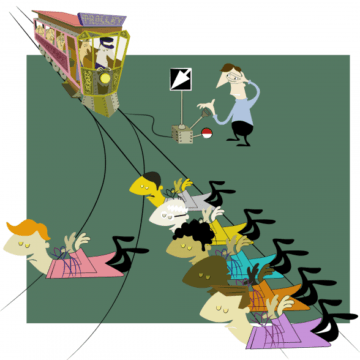

The first part of the original trolley problem goes like this. A runaway trolley is careening towards five people tied to the tracks. There’s a lever in front of you that could divert it onto a second set of tracks. Unfortunately, there is also a person tied to those tracks. You can either do nothing and let five people die or throw the switch and kill one person – but save the five. What do you do?

The first part of the original trolley problem goes like this. A runaway trolley is careening towards five people tied to the tracks. There’s a lever in front of you that could divert it onto a second set of tracks. Unfortunately, there is also a person tied to those tracks. You can either do nothing and let five people die or throw the switch and kill one person – but save the five. What do you do?

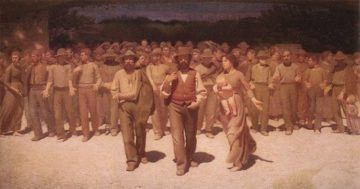

How should people on the ‘progressive’ side of politics view patriotism? That question continues to vex those who would connect with what they suppose are the feelings of the bulk of the population. The answer will vary a good deal according to which country we are considering – the French left, for instance, has a very different relationship to la patrie to that of the US or the UK. In the case of the former, the side cast as traitors has historically been seen as the right. In the USA, at least in the second half of the 20th century it has been very different: those who protested against the Vietnam war were cast as the anti patriots. And today, we still hear that the left ‘hates our country’. The accusation is a damaging one, and has been wielded with glee by conservatives whenever they have the chance. So there is a tricky task for the left, it seems: to be seen as with and not against the mass of people in their identification with the nation and its history, without abandoning an internationalist perspective that rises above the narrow nationalism of the conservative.

How should people on the ‘progressive’ side of politics view patriotism? That question continues to vex those who would connect with what they suppose are the feelings of the bulk of the population. The answer will vary a good deal according to which country we are considering – the French left, for instance, has a very different relationship to la patrie to that of the US or the UK. In the case of the former, the side cast as traitors has historically been seen as the right. In the USA, at least in the second half of the 20th century it has been very different: those who protested against the Vietnam war were cast as the anti patriots. And today, we still hear that the left ‘hates our country’. The accusation is a damaging one, and has been wielded with glee by conservatives whenever they have the chance. So there is a tricky task for the left, it seems: to be seen as with and not against the mass of people in their identification with the nation and its history, without abandoning an internationalist perspective that rises above the narrow nationalism of the conservative.

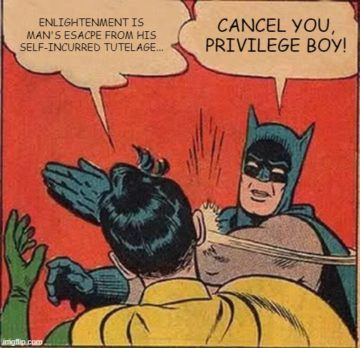

Talking about “The Enlightenment”, when understood as something like “an intellectual and philosophical movement that dominated the world of ideas in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries” (thanks,

Talking about “The Enlightenment”, when understood as something like “an intellectual and philosophical movement that dominated the world of ideas in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries” (thanks,

Sughra Raza. Untitled, April 2021.

Sughra Raza. Untitled, April 2021.

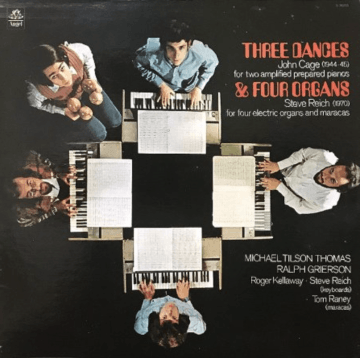

car when driving alone. Yet my momentary career as a musical performer—exceedingly brief as it may have been—enjoyed a spotlight rarely offered to others.

car when driving alone. Yet my momentary career as a musical performer—exceedingly brief as it may have been—enjoyed a spotlight rarely offered to others.