by Mike O’Brien

A very bad man once said that essence of politics is constituted by the distinction between friends and enemies, with enemies being the more important of the two. A very silly man later turned that around and articulated a politics of friendship. But let’s not indulge silliness.

The sense of enmity imagined by the very bad man was carefully distinguished from other kinds of opposition. It was not the rivalry of contestants trying to win a competition bounded by rules. It was not the opprobrium of judging some other to be morally unworthy. It was not the animosity bred by personal or parochial vendetta.

Pure enmity, which frames an opposition of properly Political character, consists in this: that in order for one’s enemy to create the world they desire, they must preclude the creation of the world which one desires oneself. And vice-versa. One may even like one’s enemy on a personal level, and attribute no moral fault or ill will to them. One may imagine that one’s enemy has no idea that they are an enemy. No matter. If, in realizing her ends, Alice (or the Republic of Alice) is likely to deny Bob (or the Commonwealth of Bob) the possibility of realizing his ends, they are politically oriented towards each other as enemies.

It need not be quite that dire. Many conflicts of interest and disputes can be resolved, or mitigated by some compromise. That is the stuff of much small “p” politics, the transactional and procedural grind of jockeying and brokering. It is infused with a logic of procedure and careerist ambition, and often some good faith attempts at governance. But such “normal” politics, the grist of political gabfests, is not a matter of existential or transcendental importance, despite histrionic appeals to the rubes about how some fiscal tweak will precipitate the end of civilization.

But some matters really don’t admit of compromise, at least between those people who take them to be the issue of their Political existence. Read more »

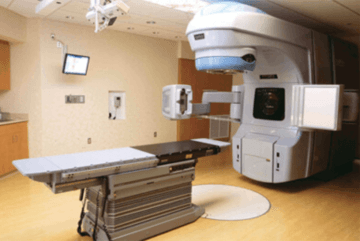

It’s the middle of July, 2020, the middle of a heat wave in the middle of the pandemic, and my first day in the radiation room. I stand in socks and starchy hospital gown before the Star Trek-ish linear accelerator, waiting for the technicians to fit me on the machine’s bed-like tray for best positioning. But in my mind I’m standing four years ago in the kitchen of my new home in Rhode Island, where beside me a cable company worker tapped in a phone number for advice about how to maneuver spotty Internet service into a happy ending. While he waited for his boss to call back, he mentioned, with a hint of wonder in his voice, “Y’know, this is my first day on the job after four months.”

It’s the middle of July, 2020, the middle of a heat wave in the middle of the pandemic, and my first day in the radiation room. I stand in socks and starchy hospital gown before the Star Trek-ish linear accelerator, waiting for the technicians to fit me on the machine’s bed-like tray for best positioning. But in my mind I’m standing four years ago in the kitchen of my new home in Rhode Island, where beside me a cable company worker tapped in a phone number for advice about how to maneuver spotty Internet service into a happy ending. While he waited for his boss to call back, he mentioned, with a hint of wonder in his voice, “Y’know, this is my first day on the job after four months.”

Climate change is such a terrifying large problem that it is hard to think sensibly about. On the one hand this makes many people prefer denial. On the other hand it can exert a warping effect on the reasoning of even those who do take it seriously. In particular, many confuse the power we have over what the lives of future generations will be like – and the moral responsibility that follows from that – with the idea that we are better off than them. These people seem to have taken the idea of the world as finite and combined it with the idea that this generation is behaving selfishly to produce a picture of us as gluttons whose overconsumption will reduce future generations to penury. But this completely misrepresents the challenge of climate change.

Climate change is such a terrifying large problem that it is hard to think sensibly about. On the one hand this makes many people prefer denial. On the other hand it can exert a warping effect on the reasoning of even those who do take it seriously. In particular, many confuse the power we have over what the lives of future generations will be like – and the moral responsibility that follows from that – with the idea that we are better off than them. These people seem to have taken the idea of the world as finite and combined it with the idea that this generation is behaving selfishly to produce a picture of us as gluttons whose overconsumption will reduce future generations to penury. But this completely misrepresents the challenge of climate change.

Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations begins with this claim:

Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations begins with this claim:

Helen Marden. Raja Ampat, 2018.

Helen Marden. Raja Ampat, 2018. I know someone—I’ll call him by his initials, KR—who is a Modi supporter. I have known KR for as long as I can remember. He is an intelligent, well-educated, well-travelled man. Now retired, he has a successful career behind him. He is Hindu, but he actively participated in the traditions and practices of other religions. Personally, I have great affection for him. Politically, we are now like oil and water. I usually avoid discussing politics with him because it inevitably ends in an argument: his view of Prime Minister Modi couldn’t be further from mine. In order to understand why people like him

I know someone—I’ll call him by his initials, KR—who is a Modi supporter. I have known KR for as long as I can remember. He is an intelligent, well-educated, well-travelled man. Now retired, he has a successful career behind him. He is Hindu, but he actively participated in the traditions and practices of other religions. Personally, I have great affection for him. Politically, we are now like oil and water. I usually avoid discussing politics with him because it inevitably ends in an argument: his view of Prime Minister Modi couldn’t be further from mine. In order to understand why people like him

John Adams was not the kind of man who easily agreed, and it showed. Nor was he the kind of man who found others agreeable. Few have accomplished so much in life while gaining so little satisfaction from it. When you think about the Four Horsemen of Independence, it’s Washington in the lead, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson and, last in the hearts of his countrymen, John Adams. You could add to that mix James Madison and even the intensely controversial Alexander Hamilton, and, once again, if you were counting fervent supporters, Adams would still bring up the rear.

John Adams was not the kind of man who easily agreed, and it showed. Nor was he the kind of man who found others agreeable. Few have accomplished so much in life while gaining so little satisfaction from it. When you think about the Four Horsemen of Independence, it’s Washington in the lead, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson and, last in the hearts of his countrymen, John Adams. You could add to that mix James Madison and even the intensely controversial Alexander Hamilton, and, once again, if you were counting fervent supporters, Adams would still bring up the rear.