by Bill Benzon

When I was a child I sought out the first blossoms of spring. The forsythia bushes were first. Then tulips perhaps? I don’t really remember. I’m guessing, though the guess is not groundless. Daffodils, yes daffodils, yellow and white.

But I DO remember the irises. Not vividly, for it was a long time ago and, as I sit here running through memories while typing these lines, none of them are vivid. But distinct. I even remember bowing down to see them more clearly. This memory is kinesthetic.

And I remember my mother kneeling in front of the flower bed. Brown slacks. Heavy gloves. She was breaking up the ground and weeding the bed. Her flowers.

She loved the irises. At least I think she did. I know I did. Why? They were tall flowers, the tallest in the bed. Was that it? Perhaps, in part, height brought the blossoms closer to the yes. Was it the color? They were colorful. It was only much later that I would learn how many different colors and colorways found homes on irises. These irises were what I have come to think of as “canonical” or “standard” irises – light blue, deep purple, white, flecks of yellow on the beards.

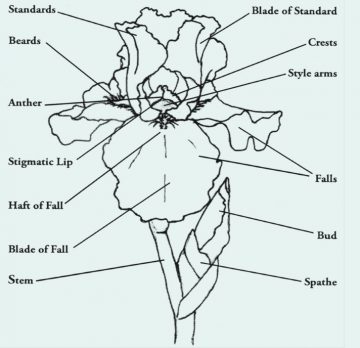

Yes, that’s what they’re called, at least colloquially, those fuzzy yellow things radiating from the center – beards. The more or less vertical petals are called standards; the droopy ones are called falls. And that complicated stuff in the center – anther, crests, stigmatic lips (stigmatic!?). It’s all so complicated.

Perhaps that’s what attracted me, the rich and complex geometry. Daisies, tulips, dandelions, petunias, pansies, even roses and daffodils – all simple and straight-forward in comparison to the iris. But the iris – how do you comprehend that shape, hold it in your mind, much less draw it or paint it, as Georgia O’Keefe of so famously did?

Flowers, yes. But worlds as well.

Imagine, let us suppose, that you are small, very small, so small that you can walk about in an iris. How do you feel when you look up and see those three standards towering over you? A bird flies overhead and its wing blocks the light momentarily. A breeze springs up and the iris is rocked about. Would you be able to keep your footing? How would it feel under foot? Are you wearing hard-soled shoes or perhaps you’re barefoot.

Perhaps you want to slide down a fall. Be careful! Don’t slip over the edge and fall to the ground. Ah, but you’ve done this before. Stopping is easy for you; climbing back up is tedious. But if you time your slide with the flower’s sway, just so, and flex your body, just so, you can propel yourself high into the air – relatively speaking, of course; we’re talking relative to the size of an iris dweller – and glide to rest atop one of those standards.

You now survey all the irises in the local stand, each with its own iris dweller. Perhaps two or three. How many dwellers can an iris support?

“Too fanciful,” you say? “Not fanciful enough,” I reply.

Imagine that an iris is a galaxy, its manifold parts consisting of sheets, folds, cylinders, and clusters of stars. Billions and billions of them, billions of miles apart. You’re the captain of the Starship Enterprise, or the Millennium Falcon – name your vehicle, make one up of to suit your fancy, a Coleridgean miracle of rare device exploring a Blakean grain of sand. How do you discover the shape of this galaxy, these many stars, you’re traversing? When the data finally comes together and you compare the image forming on your computer screen with the iris in the vase beside it – they’re alike! –what then?

We can take it a step further. Let each individual iris be a universe. All the many irises are then the alternative universes conjured up by the delirious wizards of quantum mechanics.

Let’s calibrate and measure. Let’s ponder and philosophize. Our theme is Wordsworthian: The child is father to the man.

When I was young the family would gather around the television on Sunday evenings and watch Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color, which, was organized around one of four themes, “worlds” they called them: Adventureland, Tomorrowland, Frontierland, and Fantasyland. Occasionally a Fantasyland program would show the Nutcracker Suite episode from Fantasia. As you will remember – if you’re seen it – that episode is set in a small clearing in a forest and is focused intently on plant life: flowers, shrubs, mushrooms, grasses, pine needles, leaves (but never a whole tree). You see the

world as it would be seen by creature only an inch or two tall. Perhaps you’re one of those sprites flitting about. We start in the late summer, move through autumn, and end in the winter.

It is a living world. There are no irises in it, but that’s beside the point. Disney taught us, taught me, to see beauty in a small world – I regard that episode as one of the most beautiful films ever made. That’s what it was, a whole world, a cosmos.

Disney taught me about space and space travel as well. Another episode of Fantasia – Rite of Spring – opened with a view of our solar system and then zoomed in on earth. And the Tomorrowland segment of his television show had episodes about travel to the moon, life on Mars, and, I believe, travel to Mars. Disney took me space traveling before Gene Roddenberry or George Lucas did.

Having been educated in art and science by Disney at a young age, though perhaps not so young as when I first became aware of irises, it is not so strange that I am comfortable thinking of an iris as a world, a universe. A small world, or a myriad of galaxies, but whole and complete. A cosmos.

“A flower is relatively small. Everyone has many associations with a flower – the idea of flowers. You put out your hand to touch the flower — lean forward to smell it — maybe touch it with your lips almost without thinking — or give it to someone to please them. Still — in a way — nobody sees a flower — really — it is so small — we haven’t time — and to see takes time, like to have a friend takes time… So I said to myself — I’ll paint what I see — what the flower is to me but I’ll paint it big and they will be surprised into taking time to look at it — I will make even busy New-Yorkers take time to see what I see of flowers… Well — I made you take time to look at what I saw and when you took time to really notice my flower, you hung all your own associations with flowers on my flower and you write about my flower as if I think and see what you think and see of the flower — and I don’t.”

Georgia O’Keefe, 1939, from exhibition catalogue: An American Place.

“George Mantor had an iris garden, which he improved each year by throwing out the commoner varieties. One day his attention was called to another very fine iris garden. Jealously he made some inquiries. The garden, it turned out, belonged to the man who collected his garbage.”

John Cage, Silence, 1961.

* * * * *

I photographed the irises at the Eleventh Street flower beds in Hoboken, NJ. They are maintained, I believe, by the Hoboken Garden Club.