by Mary Hrovat

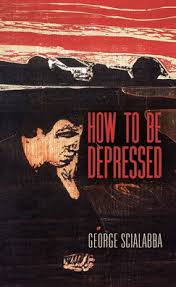

Because I have a lot of experience with depression, I approached George Scialabba’s How to Be Depressed with an almost professional curiosity. Scialabba takes a creative approach to the depression memoir, blending personal essay, interview, and his own medical records, specifically, a selection of notes written by various therapists and psychiatrists who treated him for depression between 1970 and 2016. I don’t know if I could bear to see the records kept by those who have treated me for depression, assuming they still exist, and I wasn’t sure what it would be like to read another person’s medical history.

Because I have a lot of experience with depression, I approached George Scialabba’s How to Be Depressed with an almost professional curiosity. Scialabba takes a creative approach to the depression memoir, blending personal essay, interview, and his own medical records, specifically, a selection of notes written by various therapists and psychiatrists who treated him for depression between 1970 and 2016. I don’t know if I could bear to see the records kept by those who have treated me for depression, assuming they still exist, and I wasn’t sure what it would be like to read another person’s medical history.

I found that the clinical notes, which are the core of the book, present a painfully accurate description of chronic depression and its treatment. Scialabba’s sense of being stuck is reflected in the way the same concerns come up repeatedly: procrastination, worries about being dependent, a sense of unrealized potential, feelings that he’s not accomplishing enough, especially compared to others, and concerns about whether his relationships will last. There’s not much sense of any concrete ways in which these concerns are addressed, or if they were ever successfully resolved.

This part of the book was sometimes difficult to read, but I’m glad it was written and published. It captures a certain airless circularity that I associate with my own struggles against depression. The book as a whole also reveals how the effects of depression are compounded with time. Chronic or recurring depression is qualitatively different from the experience of a single episode, and I don’t think this fact gets the attention it deserves. When Scialabba, in an interview later in the book, spoke of bitter memories, I could see why he used the word bitter.

###

The stuckness and paralysis are made more poignant by the fact that Scialabba seemed to be casting about desperately for information that might help him; he read books and articles about depression and discussed what he read with the people who were treating him. He also seemed eager to be understood. He wrote three pages of autobiographical information for his initial appointment with a psychiatrist, for example. He thought that his exit from Opus Dei, a strict Catholic organization, as a young man had played an important role in his depression and suggested more than once to a therapist that he needed to somehow revisit that difficult break to process or purge his emotions surrounding it, or to better understand why he left.

I found this very interesting. I left the Catholic Church in my early 20s after a childhood shadowed by my parents’ devout and conservative Catholicism. I sometimes feel trapped by feelings or ingrained responses linked to past experiences. I wonder sometimes if, as a society, we’ve forgotten things we used to know about how to comfort or heal people struggling to accommodate past versions of the self or past traumas.

Scialabba devised a system for recording and rating his moods. His psychiatrist, presented with the results, wrote that “things still do look kind of bleak according to the numbers,” but, in further discussion with Scialabba, he found hopeful signs: “He is still very anhedonic and feels very blocked in his writing. However, the desperation is a bit less.” As a frequently blocked, sometimes anhedonic writer, I still can’t read this without wanting to throw something and howl.

The notes go on to discuss the effects and doses of several medications. They were written in 1993 by a psychiatrist that Scialabba had been seeing since late 1991. In the context of a particularly bad episode of depression, a slight reduction in desperation isn’t negligible, but it doesn’t seem to represent much progress, especially considering the side effects of the medications. And this is not the only indication that the people who treated Scialabba sometimes had low expectations.

###

The clinical notes also constitute a powerful critique of the mental health system that Scialabba encountered. During the course of several severe depressive episodes, he received treatment consisting of therapy, medication, partial hospitalization, and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), but he still spent an awful lot of time being wretched or in a lingering “low-grade depression.” He also had to cope with the side effects of the medications and ECT, which in some cases seemed to seriously affect his quality of life.

My overall impression is that the people Scialabba saw tried to label his problems so as to pull the appropriate tool out of the toolbox (referring him for relaxation training, for example). There are reasons for treating mental illness this way, and it must work some of the time, for some problems, but there’s not much indication that he was seen as a complex person with a rich emotional life and history. The emphasis seemed to be on imposing a generic solution from outside rather than understanding him as an individual and helping him to heal.

One set of notes, obviously written to fit a template, dissects his situation neatly into a couple of problems, each with a goal, objectives, and sometimes anticipated achievement dates. These notes come across as perfunctory: “Goal (long-term): Decrease obsessive compulsive symptoms. Objectives (short-term): Patient will understand more about his anxieties and fears.” The specific plans are given only as “Individual psychotherapy. Psychopharm.”

I wonder if an overburdened person was forced to do this for a number of clients at set intervals. I wonder if the use of a prescribed format and the language of goals, objectives, and especially achievement dates made it easier to persuade insurance companies to reimburse claims for psychiatric treatment.

Insurance is mentioned several times in the notes in the context of whether Scialabba can afford treatment or whether a particular therapist is in his insurance company’s network. Concerns about jobs, money, and dependence also arise in his discussions with therapists. One broad theme of the book as a whole is the role of economic insecurity in depression. I wish it were more widely recognized that financial pressure can make it harder to treat or recover from depression, and that chronic depression can decrease lifetime earnings, sometimes dramatically. I agree with Scialabba that public financial support for people with depression would ease the suffering of many.

###

The last two chapters, an interview with a friend on the subject of depression and a series of tips for the depressed, are humane, compassionate, and far more pleasant to read. The interview in particular sparked thoughts that I want to follow up on. (For one thing, I need to read more D. H. Lawrence.) These chapters were a relief from the narrow focus of the clinical notes. I enjoyed the references to philosophy and poetry and history.

I appreciated Scialabba’s kindly advice, even the bits I had already figured out to some extent for myself. It’s good to have your experience validated by a fellow sufferer, especially because it can be very difficult even for sympathetic friends and family to understand what chronic depression is like if they haven’t experienced it themselves. He finds mornings especially difficult, as I do, and his descriptions of awakening showed me this experience in a new light: “Emerging from consciousness, you are completely undefended.” He recognizes the tremendous energy drain of being depressed as perhaps no one but another person with depression can, although I hope that maybe this book will help others to realize the toll depression can take.

How to Be Depressed wasn’t comfortable to read, but it’s a valuable book. I wish that the story had a happier ending; it ultimately seems to be a saga of scrappy survival more than one of healing. But that’s essentially my story, too, so I feel less alone, and that’s no small comfort.

###

You can see more of my work at maryhrovat.com.