by Martin Butler

Imagine a world where the prison population was a rough mirror of wider society. In such a world there is a similar spread of rich and poor, highly educated and less educated, as well as a roughly equal proportion of men and women and those from deprived areas and well-off areas. The proportions of different ethnic groups reflect those in the surrounding society, as does the age profile, and having a mental health problem bears no relation to the likelihood of being in prison, neither does being in care in any systematic way increase the chances of ending up as a young offender. In addition, there seems to be no pattern from year to year. Some years there are low levels of crime and in other years the crime rate jumps for no discernible reason. The random nature of the prison population is recognised as providing good evidence for the belief that criminality is simply a result of individuals using their free will to make bad decisions, since we are all equally capable of this. After all, it could be argued, everyone is equal in possessing free will, and crime is a conscious and fully autonomous act in which social and psychological conditions play little part. Anyone, the argument goes, can be selfish or greedy and so succumb to criminality. In such a world, the general view is that prison exists to teach these individuals the error of their ways by providing them with extra motivation to retain their self-control next time temptation beckons.

Imagine a world where the prison population was a rough mirror of wider society. In such a world there is a similar spread of rich and poor, highly educated and less educated, as well as a roughly equal proportion of men and women and those from deprived areas and well-off areas. The proportions of different ethnic groups reflect those in the surrounding society, as does the age profile, and having a mental health problem bears no relation to the likelihood of being in prison, neither does being in care in any systematic way increase the chances of ending up as a young offender. In addition, there seems to be no pattern from year to year. Some years there are low levels of crime and in other years the crime rate jumps for no discernible reason. The random nature of the prison population is recognised as providing good evidence for the belief that criminality is simply a result of individuals using their free will to make bad decisions, since we are all equally capable of this. After all, it could be argued, everyone is equal in possessing free will, and crime is a conscious and fully autonomous act in which social and psychological conditions play little part. Anyone, the argument goes, can be selfish or greedy and so succumb to criminality. In such a world, the general view is that prison exists to teach these individuals the error of their ways by providing them with extra motivation to retain their self-control next time temptation beckons.

It is instructive to ask how this imaginary world differs from, and is similar to, the actual world in which we live. What implications can we draw from the contrast? The obvious difference is that our prison population is nothing like that of the imaginary world, and I hardly need to go through the statistics that show how it’s very much not a cross-section of wider society with regards to gender, mental health, education level, family background, ethnicity, social deprivation, and so on. Read more »

I went to France to study abroad as a 20-year-old in my third year of university. At the time, I had been studying French for eight years, but when I arrived in France, I found I was unable to express myself beyond the most rudimentary statements, and I couldn’t understand the rapid-fire questions sprayed at me by curious French students. After attending a dorm party that first weekend, I realized the gap between myself and the French students was simply too large to bridge; the most I could hope for from them was small talk and polite chatter—deep, meaningful conversation, and thus friendship, would be impossible.

I went to France to study abroad as a 20-year-old in my third year of university. At the time, I had been studying French for eight years, but when I arrived in France, I found I was unable to express myself beyond the most rudimentary statements, and I couldn’t understand the rapid-fire questions sprayed at me by curious French students. After attending a dorm party that first weekend, I realized the gap between myself and the French students was simply too large to bridge; the most I could hope for from them was small talk and polite chatter—deep, meaningful conversation, and thus friendship, would be impossible. Upton Sinclair famously remarked that “it is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.” It is easy to imagine the sort of scenario that illustrates his point. A drug company rep works to increase how often a certain drug is prescribed, putting aside any worries that it is addictive. A video game designer seeks to increase the number of hours young players spend hooked on a game, not thinking about the impact this might have on their education.

Upton Sinclair famously remarked that “it is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.” It is easy to imagine the sort of scenario that illustrates his point. A drug company rep works to increase how often a certain drug is prescribed, putting aside any worries that it is addictive. A video game designer seeks to increase the number of hours young players spend hooked on a game, not thinking about the impact this might have on their education.

“People in the know know him.” That’s what his English translator, Peter Constantine, told me. Grzegorz Kwiatkowski is becoming an important poetic voice from today’s Poland, with six volumes of poetry, and translated editions on the way. His translator added, “He has a strange poetic voice, very original and stark.”

“People in the know know him.” That’s what his English translator, Peter Constantine, told me. Grzegorz Kwiatkowski is becoming an important poetic voice from today’s Poland, with six volumes of poetry, and translated editions on the way. His translator added, “He has a strange poetic voice, very original and stark.”

Most cinemas have been open for some time where I live. After having been indoors in restaurants and bars a few times, I was slowly reintroduced to the pleasures of sharing a space with strangers. And finally it felt like the right moment to, once again, set foot in a cinema.

Most cinemas have been open for some time where I live. After having been indoors in restaurants and bars a few times, I was slowly reintroduced to the pleasures of sharing a space with strangers. And finally it felt like the right moment to, once again, set foot in a cinema. Among other members in the Economics faculty at Cambridge, there was the great Italian scholar, Piero Sraffa. He was administratively the professor-in-charge of us, graduate students. So I met him a few times in that connection, but never quite intellectually engaged with him, partly because by that time he was a bit reclusive and did not teach classes or attend seminars; but also because I was so much in awe of his reputation in areas where I had little expertise. His work in Economics was path-breaking in taking price theory to its classical roots, he had an influence on Wittgenstein’s philosophy (which the latter acknowledged), and he was a close friend of the Italian Marxist thinker, Antonio Gramsci (when the latter was jailed by Mussolini in 1926, Sraffa used to regularly supply him with books and even pen and paper, with which Gramsci wrote his famous Prison Notebooks, procured by Sraffa from the prison authorities after Gramsci’s death in 1937).

Among other members in the Economics faculty at Cambridge, there was the great Italian scholar, Piero Sraffa. He was administratively the professor-in-charge of us, graduate students. So I met him a few times in that connection, but never quite intellectually engaged with him, partly because by that time he was a bit reclusive and did not teach classes or attend seminars; but also because I was so much in awe of his reputation in areas where I had little expertise. His work in Economics was path-breaking in taking price theory to its classical roots, he had an influence on Wittgenstein’s philosophy (which the latter acknowledged), and he was a close friend of the Italian Marxist thinker, Antonio Gramsci (when the latter was jailed by Mussolini in 1926, Sraffa used to regularly supply him with books and even pen and paper, with which Gramsci wrote his famous Prison Notebooks, procured by Sraffa from the prison authorities after Gramsci’s death in 1937).

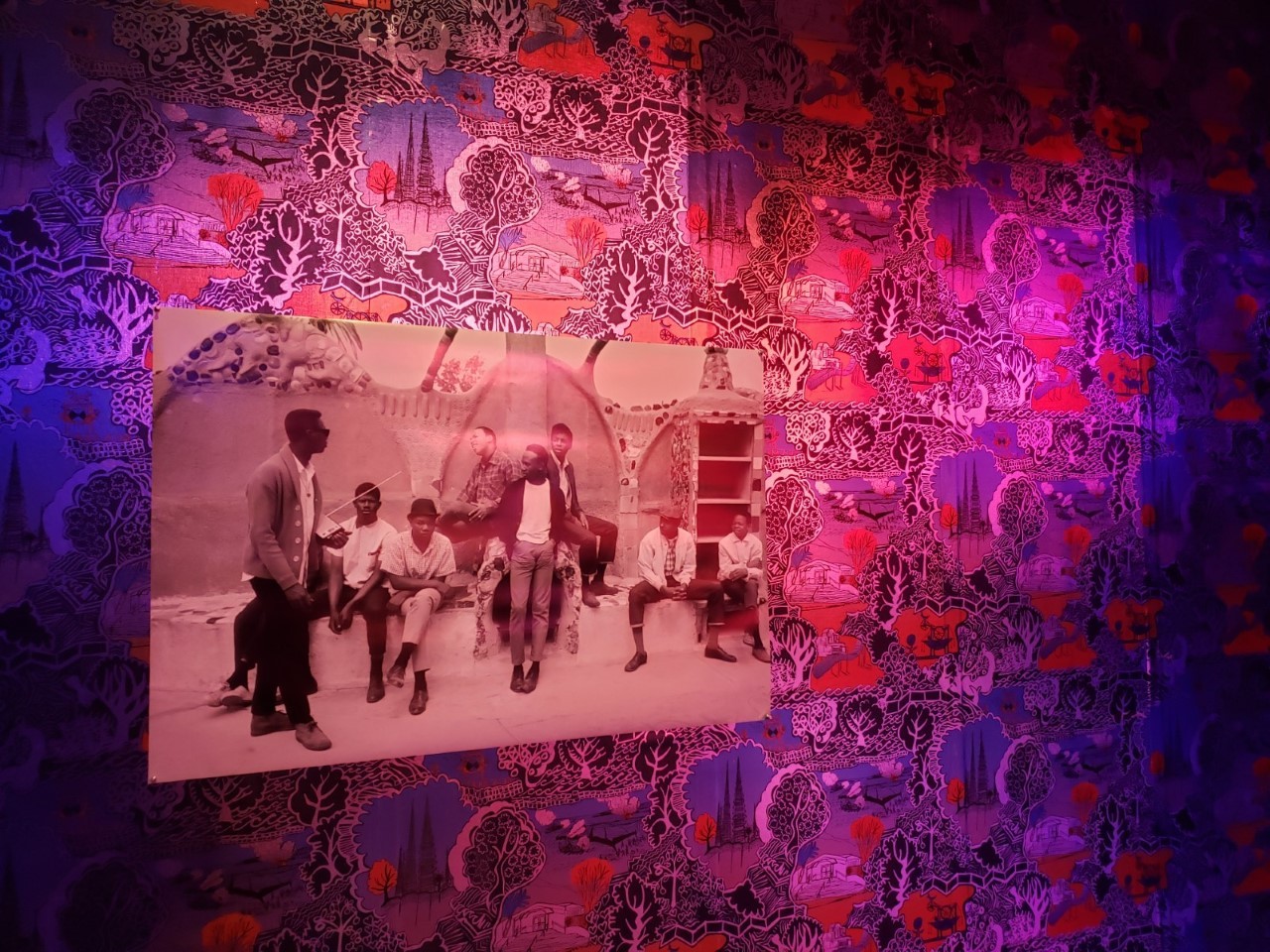

Cauleen Smith. Space Station Chinoiserie #1: Take hold of the Clouds, 2018.

Cauleen Smith. Space Station Chinoiserie #1: Take hold of the Clouds, 2018. Last night I (Danielle Spencer) went to the New York Film Festival screening of Memoria (dir. Apichatpong Weerasethakul) in Alice Tully hall at Lincoln Center. I last joined a large gathering 19 months ago, in March of 2020.

Last night I (Danielle Spencer) went to the New York Film Festival screening of Memoria (dir. Apichatpong Weerasethakul) in Alice Tully hall at Lincoln Center. I last joined a large gathering 19 months ago, in March of 2020.

In the world of Star Trek, no one ever goes hungry or lacks access to healthcare. No one wants for housing, education, social inclusion or any other basic need. In fact, no citizen of the United Federation of Planets is ever seen to pay for everyday goods or services, only for gambling or special entertainments. The Federation suffers no scarcity of any kind. All waste is presumably fed into the replicators and turned into fresh food or new clothes or whatever is needed. Yet despite ample social safety nets, there’s no end to internecine politicking, human foibles and failures, corruption and vanity, charisma and venality. The world of Star Trek appeals so widely, I think, because it presents us with something colorfully short of a utopia, a flawed human attempt toward a just, caring, and individually enabling social order. It imagines a society based on a shared set of human values—fairness, cooperation, political and economic egalitarianism—where basic human needs are equitably answered so that no one has to compete for basic subsistence and wellbeing. As the venerable

In the world of Star Trek, no one ever goes hungry or lacks access to healthcare. No one wants for housing, education, social inclusion or any other basic need. In fact, no citizen of the United Federation of Planets is ever seen to pay for everyday goods or services, only for gambling or special entertainments. The Federation suffers no scarcity of any kind. All waste is presumably fed into the replicators and turned into fresh food or new clothes or whatever is needed. Yet despite ample social safety nets, there’s no end to internecine politicking, human foibles and failures, corruption and vanity, charisma and venality. The world of Star Trek appeals so widely, I think, because it presents us with something colorfully short of a utopia, a flawed human attempt toward a just, caring, and individually enabling social order. It imagines a society based on a shared set of human values—fairness, cooperation, political and economic egalitarianism—where basic human needs are equitably answered so that no one has to compete for basic subsistence and wellbeing. As the venerable