by Thomas O’Dwyer

If the recent COP26 Climate Change marathon in Scotland was the last best hope for humankind, where can I reserve a seat on Elon Musk’s flight to Mars? With delegates jetting into Glasgow from around 200 countries, the event started to look like an episode of Monty Python’s Flying Circus with a cast of thousands. To a chorus of “Blah, blah, blah!” from Greta Thunberg’s street warriors, the first dispatches out of the media paddock were mostly cheap shots at the idiocies the gathering spawned. Like the giant foot stomping on dissent in a Python sketch, the massive carbon footprint generated by COP26 squashed all previous records for a climate crisis conference. Its emissions of 102,500 tonnes of CO2 equivalent was more than double that of the last UN climate summit. About 60 per cent of that represented the international travel of the 39,000 official delegates to the talks. Many of those attending were bag carriers, aides, professional lobbyists and other hangers-on. UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson flew by private jet to Cop26 from London, but after an outpouring of media scorn, he opted for the train on a subsequent visit.

As for cheap shots, a bloated delegation from impoverished Zimbabwe got theirs from a local supermarket, widely photographed loading up carts with hundreds of dollars worth of Scotland’s finest whiskies. They were later filmed celebrating President Emmerson Mnangagwa’s arrival at a raucous party on an Edinburgh beach, accompanied by much derision and anger on social media at home on the theme of, “Why are our leaders there, for whisky and T-shirts?” Many experts considered the event crucial for the future of our planet, but its geeky title remained mostly unrecognised by the public. Vox pop interviews on the streets in Scottish cities revealed that few knew what COP26 meant, and many seemed confused as to whether it was a climate or an environmental conference or what it was supposed to achieve. It’s a fair guess that this low level of public engagement was universal, explaining why many editors of popular media chose to run click-bait stories laden with those cheap shots and red herrings.

COP stands for Conference of the Parties, and it convened for the 26th time during the first two weeks of November. Read more »

There was another well-known economist who later claimed that he was my student at MIT, but for some reason I cannot remember him from those days: this was Larry Summers, later Treasury Secretary and Harvard President. Once I was invited to give a keynote lecture at the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics at Islamabad, and on the day of my lecture they told me that Summers (then Vice President at the World Bank) was in town, and so they had invited him to be a discussant at my lecture. After my lecture, when Larry rose to speak he said, “I am going to be critical of Professor Bardhan for several reasons, one of them being personal: he may not remember, when I was a student in his class at MIT, he gave me the only B+ grade I have ever received in my life”. When it came to my turn to reply to his criticisms of my talk, I said, “I don’t remember giving him a B+ at MIT, but today after listening to him I can tell you that he has improved a little, his grade now is A-“, and then proceeded to explain why it was not an A. The Pakistani audience seemed to lap it up, particularly because until then everybody there was deferential to Larry.

There was another well-known economist who later claimed that he was my student at MIT, but for some reason I cannot remember him from those days: this was Larry Summers, later Treasury Secretary and Harvard President. Once I was invited to give a keynote lecture at the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics at Islamabad, and on the day of my lecture they told me that Summers (then Vice President at the World Bank) was in town, and so they had invited him to be a discussant at my lecture. After my lecture, when Larry rose to speak he said, “I am going to be critical of Professor Bardhan for several reasons, one of them being personal: he may not remember, when I was a student in his class at MIT, he gave me the only B+ grade I have ever received in my life”. When it came to my turn to reply to his criticisms of my talk, I said, “I don’t remember giving him a B+ at MIT, but today after listening to him I can tell you that he has improved a little, his grade now is A-“, and then proceeded to explain why it was not an A. The Pakistani audience seemed to lap it up, particularly because until then everybody there was deferential to Larry. What does it mean to say that everyone is equal? It does not mean that everyone has (or should have) the same amount of nice things, money, or happiness. Nor does it mean that everyone’s abilities or opinions are equally valuable. Rather, it means that everyone has the same – equal – moral status as everyone else. It means, for example, that the happiness of any one of us is just as important as the happiness of anyone else; that a promise made to one person is as important as that made to anyone else; that a rule should count the same for all. No one deserves more than others – more chances, more trust, more empathy, more rewards – merely because of who or what they are.

What does it mean to say that everyone is equal? It does not mean that everyone has (or should have) the same amount of nice things, money, or happiness. Nor does it mean that everyone’s abilities or opinions are equally valuable. Rather, it means that everyone has the same – equal – moral status as everyone else. It means, for example, that the happiness of any one of us is just as important as the happiness of anyone else; that a promise made to one person is as important as that made to anyone else; that a rule should count the same for all. No one deserves more than others – more chances, more trust, more empathy, more rewards – merely because of who or what they are. Obviously, “Donald Trump” here is a placeholder for any political figure who one wishes to insult. But the joke raises an interesting question. What kind of work , if any, is shameful? And it also suggests a way of posing the question: viz. what kind of work might a child be ashamed to admit that their parents performed? This is an interesting dinner table conversation topic.

Obviously, “Donald Trump” here is a placeholder for any political figure who one wishes to insult. But the joke raises an interesting question. What kind of work , if any, is shameful? And it also suggests a way of posing the question: viz. what kind of work might a child be ashamed to admit that their parents performed? This is an interesting dinner table conversation topic.

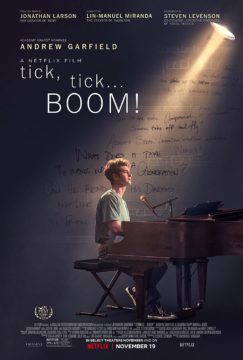

Tick, Tick . . . Boom!

Tick, Tick . . . Boom!