by Thomas R. Wells

“The poorest he that is in England has a life to live as the greatest he” (Thomas Rainsborough, spokesman for the Levellers at the Putnam Debates)

What does it mean to say that everyone is equal? It does not mean that everyone has (or should have) the same amount of nice things, money, or happiness. Nor does it mean that everyone’s abilities or opinions are equally valuable. Rather, it means that everyone has the same – equal – moral status as everyone else. It means, for example, that the happiness of any one of us is just as important as the happiness of anyone else; that a promise made to one person is as important as that made to anyone else; that a rule should count the same for all. No one deserves more than others – more chances, more trust, more empathy, more rewards – merely because of who or what they are.

What does it mean to say that everyone is equal? It does not mean that everyone has (or should have) the same amount of nice things, money, or happiness. Nor does it mean that everyone’s abilities or opinions are equally valuable. Rather, it means that everyone has the same – equal – moral status as everyone else. It means, for example, that the happiness of any one of us is just as important as the happiness of anyone else; that a promise made to one person is as important as that made to anyone else; that a rule should count the same for all. No one deserves more than others – more chances, more trust, more empathy, more rewards – merely because of who or what they are.

This ideal of equality is a point on which pretty much all moral philosophers agree, and it is also the ideological foundation for liberal states. In the last centuries, much progress has been made in realising it in institutions like universal suffrage, the rule of law (where justice is portrayed wearing a blindfold), and impersonally (bureaucratically) administered social insurance systems. But this equality revolution remains an incomplete and fragile achievement. It is in perpetual conflict with our all too human moral psychology, which evolved to manage the micro-politics of small groups and is highly focused on personal relationships and social status; with assigning privileges rather than recognising rights.

Who you are known to know still counts for far too much in how we get treated. Within the state and between the state and those it governs, personal relationships are much less significant than they used to be after a centuries long effort to redescribe them as ‘corruption’. But they are merely down; not out. Read more »

Obviously, “Donald Trump” here is a placeholder for any political figure who one wishes to insult. But the joke raises an interesting question. What kind of work , if any, is shameful? And it also suggests a way of posing the question: viz. what kind of work might a child be ashamed to admit that their parents performed? This is an interesting dinner table conversation topic.

Obviously, “Donald Trump” here is a placeholder for any political figure who one wishes to insult. But the joke raises an interesting question. What kind of work , if any, is shameful? And it also suggests a way of posing the question: viz. what kind of work might a child be ashamed to admit that their parents performed? This is an interesting dinner table conversation topic.

Tick, Tick . . . Boom!

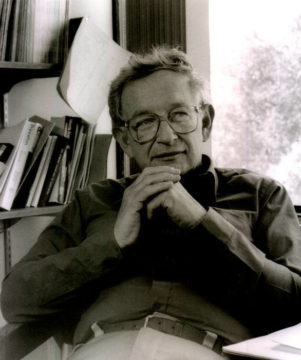

Tick, Tick . . . Boom! Of the senior professors at MIT other than Samuelson and Solow, I had a somewhat close relationship with Paul Rosenstein-Rodan, a pioneer in development economics. He had grown up in Vienna and taught in England before reaching MIT. He had advised governments in many countries, and was full of stories. In India he knew Nehru and Sachin Chaudhuri well. He had an excited, omniscient way of talking about various things. At the beginning of our many long conversations he asked me what my politics was like. I said “Left of center, though many Americans may consider it too far left while several of my Marxist friends in India do not consider it left enough”. As someone from ‘old Europe’ he understood, and immediately put his hand on his heart and said “My heart too is located slightly left of center”.

Of the senior professors at MIT other than Samuelson and Solow, I had a somewhat close relationship with Paul Rosenstein-Rodan, a pioneer in development economics. He had grown up in Vienna and taught in England before reaching MIT. He had advised governments in many countries, and was full of stories. In India he knew Nehru and Sachin Chaudhuri well. He had an excited, omniscient way of talking about various things. At the beginning of our many long conversations he asked me what my politics was like. I said “Left of center, though many Americans may consider it too far left while several of my Marxist friends in India do not consider it left enough”. As someone from ‘old Europe’ he understood, and immediately put his hand on his heart and said “My heart too is located slightly left of center”.

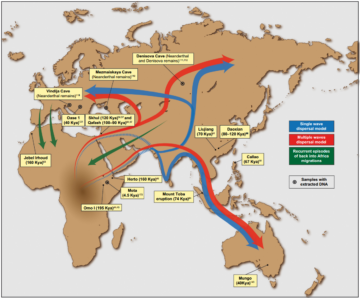

Our human story has never been simple or monotonous. In fact, it has been nothing less than epic. Beginning from relatively small populations in Africa, our ancestors

Our human story has never been simple or monotonous. In fact, it has been nothing less than epic. Beginning from relatively small populations in Africa, our ancestors  hookers rested after walking Hollywood Boulevard, or at least that’s what my mother once said of her counterparts who lived in rooms above the garages of a small apartment building on a busy street. While waiting for my father to return from prison, we lived in one of the garages, converted into a shelter.

hookers rested after walking Hollywood Boulevard, or at least that’s what my mother once said of her counterparts who lived in rooms above the garages of a small apartment building on a busy street. While waiting for my father to return from prison, we lived in one of the garages, converted into a shelter. Catharine Ahearn. Incredible Hulk, 2014. In the exhibition “Everything Falls Faster Than An Anvil”.

Catharine Ahearn. Incredible Hulk, 2014. In the exhibition “Everything Falls Faster Than An Anvil”.