Sughra Raza. Bey Unvaan. Anza-Borrego Desert Park, Calfornia, 2017.

Sughra Raza. Bey Unvaan. Anza-Borrego Desert Park, Calfornia, 2017.

Digital photograph.

Sughra Raza. Bey Unvaan. Anza-Borrego Desert Park, Calfornia, 2017.

Sughra Raza. Bey Unvaan. Anza-Borrego Desert Park, Calfornia, 2017.

Digital photograph.

by Joseph Shieber

One of the most famous philosophical arguments is Pascal’s Wager, an attempt by the 17th century French mathematician and philosopher Blaise Pascal to provide ammunition for religious believers in their struggles against nonbelief.

The Wager works like this. First, there are two possible states of affairs that you’re to consider: either God exists or God doesn’t exist. Second, there are two possible attitudes you could adopt with respect to God’s existence: either you believe that God exists or you don’t believe that God exists (you either actively believe that God doesn’t exist or you withhold belief in God’s existence.

This gives us the following possible combinations, with their resultant outcomes:

This way of setting out the case for belief vs. nonbelief does not do the nonbeliever any favors.

If you don’t believe, the optimal result would be that God doesn’t exist. Then you would have one more true belief than the rubes who falsely believe (assuming of course that you actively disbelieve, rather than merely withholding belief in God’s existence). The other possibility for non-believers, however, is truly horrible. If you don’t believe and God DOES exist, then you are damned to an eternity of suffering in hell.

Contrast this with the situation for believers. The worst case for them is that they believe, but God doesn’t exist. Still not so bad! Just one additional false belief! If, however, God DOES exist, then the believer can look forward to a reward of eternal life in heaven.

Now, there are a variety of ways to object to the set-up of the Wager. Read more »

by Jochen Szangolies

In the 1994 science fiction film Star Trek Generations, while attempting to locate the missing Captain Picard, Lt. Cmdr. Data is given the task to scan for life-forms on the planet below. Data, an android having recently been outfitted with an emotion chip, proceeds to proclaim his love for the task, and makes up a little impromptu ditty while operating his console, to the bewilderment of his crew mates.

The scene plays as comic relief, but is not without some poignancy. The status of Data himself, whether he can be said to be himself ‘alive’ and therefore worthy of the special protection generally awarded to living things, is a recurring plot thread throughout the run of Star Trek: The Next Generation. In his struggle to become ‘more human’, his attainment of emotions marks a major milestone. Having thus been initiated into the rank of an—albeit artificial—life-form, one might cast his task as not so much a scientific, but a philosophical one: searching for others of his kind.

It is then somewhat odd that there is apparently a mechanizable answer to the question ‘what is life?’, some algorithm performed on the appropriate measurement data returning a judgment on the status of any blob of matter under investigation as either alive or not. If there is some mechanical criterion separating life from non-life, then how was Data’s own status ever in question? Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Ruchira Paul

“Sewer designs… For me, it took about a year to exhaust my fascination with the underground maze of waste. That’s when I realized the single most important point to grasp about designing sewer lines is that the shit must flow downhill. That’s all one needs to know. Nothing else matters.” So muses Emma, a smart young sewer engineer and the protagonist of Sara Goudarzi’s debut novel The Almond in the Apricot. The book takes us through the convoluted maze of Emma’s own inner turmoil that begins to blur the boundaries between her physical world and her dreams.

“Sewer designs… For me, it took about a year to exhaust my fascination with the underground maze of waste. That’s when I realized the single most important point to grasp about designing sewer lines is that the shit must flow downhill. That’s all one needs to know. Nothing else matters.” So muses Emma, a smart young sewer engineer and the protagonist of Sara Goudarzi’s debut novel The Almond in the Apricot. The book takes us through the convoluted maze of Emma’s own inner turmoil that begins to blur the boundaries between her physical world and her dreams.

Emma’s troubles begin shortly after the sudden accidental death of her best friend and confidante Spencer to whom she had felt more attracted physically and emotionally than she does to her kind and decent boyfriend Peter. The tragedy negatively affects both her personal and professional lives. Without the lively presence of Spencer as the third side of the triangle, Emma finds her romantic interest in Peter dwindling. Peter’s kindness and decency begin to strike Emma as bland attributes – “neither acidic nor alkaline, a perfect pH 7.0 of a human.” She becomes careless and negligent at work. The most worrisome manifestation of Emma’s state of mind is the appearance of vivid, disturbing nightly dreams that encroach upon her waking hours. Emma begins to lose her footing in the real world, becoming exhausted, erratic and suspicious as also a bit of a schemer who no longer has too many qualms about betraying those close to her. Read more »

by Michael Abraham-Fiallos

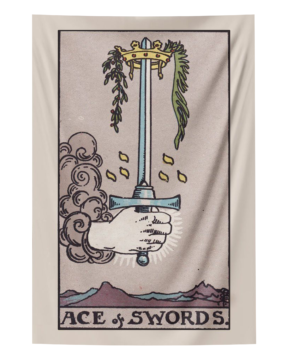

When I am not doing well in my own head, I turn to the tarot. While no substitute for therapy or psychiatry, the tarot has an ancient function that is symbiotic with these modern methods for coping with the wild unruliness of the mind. I know it sounds silly. But before there was psychology and medicine, there was magic, and that is not silly at all. People crave rituals and symbols; they crave narratives about themselves with which to play and to experiment. And the tarot is nothing if not an arcane form of play and experimentation with the idea of the self, packed with ritual and narrative and symbol. Magic, you see, is a very minor thing. It does not make great things happen, and, when it is practiced honestly and forthrightly, it does not claim to make great things happen. Instead, magic is meant to open up little moments, little apertures into self-understanding, that allow for the flourishing of subjects in an otherwise mean and obscure world. It is difficult to be a subject in the world; it is a task with no guidebook and with few obvious parameters. Little practices that seek after the integration of the self with the world, that seek to make distinct and clear not only who the self is but what the self means and is capable of accomplishing and being with the materials of the world at hand—these kinds of practices, which include both the tarot and psychotherapy (the latter being perhaps a practice of magic in our modern lives), make it feel immanently possible to exist and to grow and to change. And what feels possible becomes possible.

When I am not doing well in my own head, I turn to the tarot. While no substitute for therapy or psychiatry, the tarot has an ancient function that is symbiotic with these modern methods for coping with the wild unruliness of the mind. I know it sounds silly. But before there was psychology and medicine, there was magic, and that is not silly at all. People crave rituals and symbols; they crave narratives about themselves with which to play and to experiment. And the tarot is nothing if not an arcane form of play and experimentation with the idea of the self, packed with ritual and narrative and symbol. Magic, you see, is a very minor thing. It does not make great things happen, and, when it is practiced honestly and forthrightly, it does not claim to make great things happen. Instead, magic is meant to open up little moments, little apertures into self-understanding, that allow for the flourishing of subjects in an otherwise mean and obscure world. It is difficult to be a subject in the world; it is a task with no guidebook and with few obvious parameters. Little practices that seek after the integration of the self with the world, that seek to make distinct and clear not only who the self is but what the self means and is capable of accomplishing and being with the materials of the world at hand—these kinds of practices, which include both the tarot and psychotherapy (the latter being perhaps a practice of magic in our modern lives), make it feel immanently possible to exist and to grow and to change. And what feels possible becomes possible.

I think an example is necessary. I decided to do a tarot spread specifically for this essay, to lay bare exactly what I mean when I say that the tarot offers an opportunity for playing with the notion of oneself in the world. Before I take you into that spread, though, I want to explain the tarot as best as I can. Read more »

I awoke yesterday morning to find these ice crystals which had formed on the glass of my window at Akola, near the town of Ii in northern Finland, which is pretty much on the arctic circle (65.3° North latitude). The temperature outside was around -21° C (or around -6° F). The wind chill factor? Don’t ask!

by Derek Neal

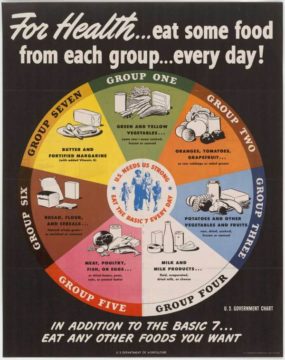

What to eat? A seemingly simple question, but one that has become increasingly difficult to answer. And why is that? My initial hypothesis is that as modern society becomes more and more distanced from traditional and local cuisines, people have less guidance as to what to eat; this puts increased pressure on individuals to make a conscious choice, but with unclear and often conflicting information about how to make this choice. In other words, people used to just eat whatever their grandparents had eaten, and this worked relatively well. Now, with an overabundance of choice and ignorance of one’s own past, we are lost, wandering through the supermarket aisles like a traveler lost in the woods. Thus, we see diets, meal plans, food delivery apps, and a myriad of other things jump in to fill the void that has been abdicated by family and community. But this story is perhaps so obvious that it does not need retelling. It is, after all, the story of the modern, global world. Nevertheless, it’s useful to pause, look around, and ask ourselves, “How did we get here? What is this place?” Let me sketch a few examples of people attempting to answer our initial question, “What to eat?” to help illustrate our general predicament.

What to eat? A seemingly simple question, but one that has become increasingly difficult to answer. And why is that? My initial hypothesis is that as modern society becomes more and more distanced from traditional and local cuisines, people have less guidance as to what to eat; this puts increased pressure on individuals to make a conscious choice, but with unclear and often conflicting information about how to make this choice. In other words, people used to just eat whatever their grandparents had eaten, and this worked relatively well. Now, with an overabundance of choice and ignorance of one’s own past, we are lost, wandering through the supermarket aisles like a traveler lost in the woods. Thus, we see diets, meal plans, food delivery apps, and a myriad of other things jump in to fill the void that has been abdicated by family and community. But this story is perhaps so obvious that it does not need retelling. It is, after all, the story of the modern, global world. Nevertheless, it’s useful to pause, look around, and ask ourselves, “How did we get here? What is this place?” Let me sketch a few examples of people attempting to answer our initial question, “What to eat?” to help illustrate our general predicament.

Bill Murray in Lost in Translation calls home to his wife and says he wants to make a change: he wants to stop eating “all that pasta,” and instead wants to start eating healthy food, “like Japanese food.” Murray’s character, being an American, is already at a disadvantage when it comes to knowing what to eat, as he most likely does not have a culinary tradition to call his own. Thus, he insists not on a switch from American cuisine (whatever that would be) to something else, but a switch from Italian to Japanese cuisine. Read more »

by Pranab Bardhan

All of the articles in this series can be found here.

Even though my ISI office was in the Planning Commission building in New Delhi I was living in an apartment complex far away in ‘Old’ Delhi, nearer Delhi University. The main attraction of staying there was the number of academic friends who lived in the same complex, apart from its being in a rather open, leafy, quieter part of the city (the hilly walkway at the back—called ‘the ridge’– was full of parrots and monkeys). My MIT friend, Mrinal, who stayed there arranged with the landlord for our accommodation.

Even though my ISI office was in the Planning Commission building in New Delhi I was living in an apartment complex far away in ‘Old’ Delhi, nearer Delhi University. The main attraction of staying there was the number of academic friends who lived in the same complex, apart from its being in a rather open, leafy, quieter part of the city (the hilly walkway at the back—called ‘the ridge’– was full of parrots and monkeys). My MIT friend, Mrinal, who stayed there arranged with the landlord for our accommodation.

Mrinal was then a popular teacher at Delhi School of Economics (DSE). His wife Eva was a feisty and resourceful Italian woman, coming from a political family—her father was an active anti-fascist, killed in Rome in 1944 by a Nazi ambush; her maternal uncle was the famous development economist Albert Hirschman (whom I admired and met a few times at Princeton). Eva coming for the first time to India quickly figured out the tricks of negotiating the daily complications of life in Delhi, and by the time we arrived she, a savvy foreigner, helped us settle in Delhi. It used to be quite a spectacle to see a sari-clad Eva haggling in street Hindi with the wily shopkeepers of Delhi and relishing it.

Hardly any day went without my long chats with Mrinal. We shared a great deal in our interests. His wacky sense of humor was combined with a serious thoughtfulness on many issues. On political issues in particular he was one of the wisest and shrewdest observers I have known. When Eva later left him and went with (and married) his best friend since their boyhood in Santiniketan, Amartya Sen, I saw a different side of Mrinal, that of pained dignity and graceful fortitude. Read more »

by Michael Liss

I come to praise bakeries past and present. And older men and women faithfully carrying out their duties to their grandchildren.

I come to praise bakeries past and present. And older men and women faithfully carrying out their duties to their grandchildren.

Of bakeries, once too many to count in my city, but, like old loves, we remember Glaser’s (closed every August so the family could return to Germany), Gertels (each cake caused a local sugar shortage), and Lichtman’s (the Times called it “The Da Vinci of Dough”). Still with us, Moishe’s and Andre’s, Veniero and Ferrara’s, and for the breads of your dreams, Orwashers and Eli’s.

I could go on. In fact, I could go on for some time, but there’s a Supreme Court nomination and the Midterms looming, and duty comes before carb-loading. To be more precise, in this essay, it comes both before and after carb-loading but, be patient with me while I take the strings off the boxes and plate the pastry.

As a President gets top billing, even over the dearly departed French pastry shop on First with the spectacular petit fours and crusty rolls that launched a thousand crumbs, it’s time for me to turn to Joe. However, I will not be insulted if you skip the meal and go directly to dessert. You will find it below the fold.

When I think of Biden, I can’t get out of my mind a quote attributed to Lincoln: “Elections belong to the people. It’s their decision. If they decide to turn their back on the fire and burn their behinds, then they will just have to sit on their blisters.” Read more »

by Usha Alexander

[This is the sixteenth in a series of essays, On Climate Truth and Fiction, in which I raise questions about environmental distress, the human experience, and storytelling. All the articles in this series can be read here.]

Was it inevitable, this ongoing anthropogenic, global mass-extinction? Do mass destruction, carelessness, and hubris characterize the only way human societies know how to be in the world? It may seem true today but we know that it wasn’t always so. Early human societies in Africa—and many later ones around the world—lived without destroying their environments for long millennia. We tend to write off the vast period before modern humans left Africa as a time when “nothing much was happening” in the human story. But a great deal was actually happening: people explored, discovered, invented, and made decisions about how to live, what to eat, how to relate to each other; they observed and learned from the intricate and changing life around them. From this they fashioned sense and meaning, creative mythologies, art and humor, social institutions and traditions, tools and systems of knowledge. Yet it’s almost as though, if people aren’t busily depleting or destroying their local environments, we regard them as doing nothing.

Was it inevitable, this ongoing anthropogenic, global mass-extinction? Do mass destruction, carelessness, and hubris characterize the only way human societies know how to be in the world? It may seem true today but we know that it wasn’t always so. Early human societies in Africa—and many later ones around the world—lived without destroying their environments for long millennia. We tend to write off the vast period before modern humans left Africa as a time when “nothing much was happening” in the human story. But a great deal was actually happening: people explored, discovered, invented, and made decisions about how to live, what to eat, how to relate to each other; they observed and learned from the intricate and changing life around them. From this they fashioned sense and meaning, creative mythologies, art and humor, social institutions and traditions, tools and systems of knowledge. Yet it’s almost as though, if people aren’t busily depleting or destroying their local environments, we regard them as doing nothing.

Of course, it is a normal dynamic of evolution that one species occasionally will outcompete another and drive it toward extinction. But for most of their time on Earth, human beings were not having an outsized, annihilating effect on the life around them, rather than co-evolving with it. That evolution was at least as much cultural as it was a matter of flesh. What people consumed, how they obtained it, and how quickly they used it up has always played a role in the stability and evolution of any ecosystem of which humans were a part. How fast human populations grew, how they sheltered, what they trampled and destroyed or nourished and promoted—all of this affected their environment. Naturally, their interactions with the environment were always driven by what they wanted. And what people want is intimately driven by what they believe, as in the stories they tell themselves. One thing we can safely presume: those who understood their own social continuity as contingent upon that of their environment weren’t telling the same stories we tell today. Read more »

by Danielle Spencer

The theme of home—as a topic, question—is woven throughout Siri Hustvedt’s excellent new essay collection, Mothers, Fathers, and Others. In the first essay, “Tillie,” about her grandmother, Hustvedt also recalls her grandfather, Lars Hustvedt, who was born and lived in the United States, and first traveled to his own father’s home in Voss, Norway, when he was seventy years old. “Family lore has it that he knew ‘every stone’ on the family farm, Hustveit, by heart,” Hustvedt writes. “My grandfather’s father must have been homesick, and that homesickness and the stories that accompanied the feeling must have made his son homesick for a home that wasn’t home but rather an idea of home.”

The theme of home—as a topic, question—is woven throughout Siri Hustvedt’s excellent new essay collection, Mothers, Fathers, and Others. In the first essay, “Tillie,” about her grandmother, Hustvedt also recalls her grandfather, Lars Hustvedt, who was born and lived in the United States, and first traveled to his own father’s home in Voss, Norway, when he was seventy years old. “Family lore has it that he knew ‘every stone’ on the family farm, Hustveit, by heart,” Hustvedt writes. “My grandfather’s father must have been homesick, and that homesickness and the stories that accompanied the feeling must have made his son homesick for a home that wasn’t home but rather an idea of home.”

Homesick for a home that wasn’t home but rather an idea of home. Yet home is always an idea of home, even when it is indeed a home we have experienced. Lars’ memory evinces philosopher Derek Parfit’s discussion of “q-memory”—a memory of an experience which the subject didn’t experience. Rachael’s implanted “memories” in Blade Runner are q-memories (and perhaps Deckard’s are as well, at least in the Director’s Cut.) According to Parfit, the notion that I am the person who experienced my memory is an assumption I make simply because I presume that I don’t have q-memories. Thus

on our definition every memory is also a q-memory. Memories are, simply, q-memories of one’s own experiences. Since this is so, we could afford now to drop the concept of memory and use in its place the wider concept q-memory. If we did, we should describe the relation between an experience and what we now call a “memory” of this experience in a way which does not presuppose that they are had by the same person.

As André Aciman puts it, “things always seem, they never are.” In his essay “Arbitrage,” he describes his own experience of being, in Hustvedt’s words, homesick for a home that wasn’t home but rather an idea of home—or perhaps moreso in his case, homesick for missing home. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Inside Out, Boston, 2021.

Sughra Raza. Inside Out, Boston, 2021.

Digital photograph.

by Akim Reinhardt

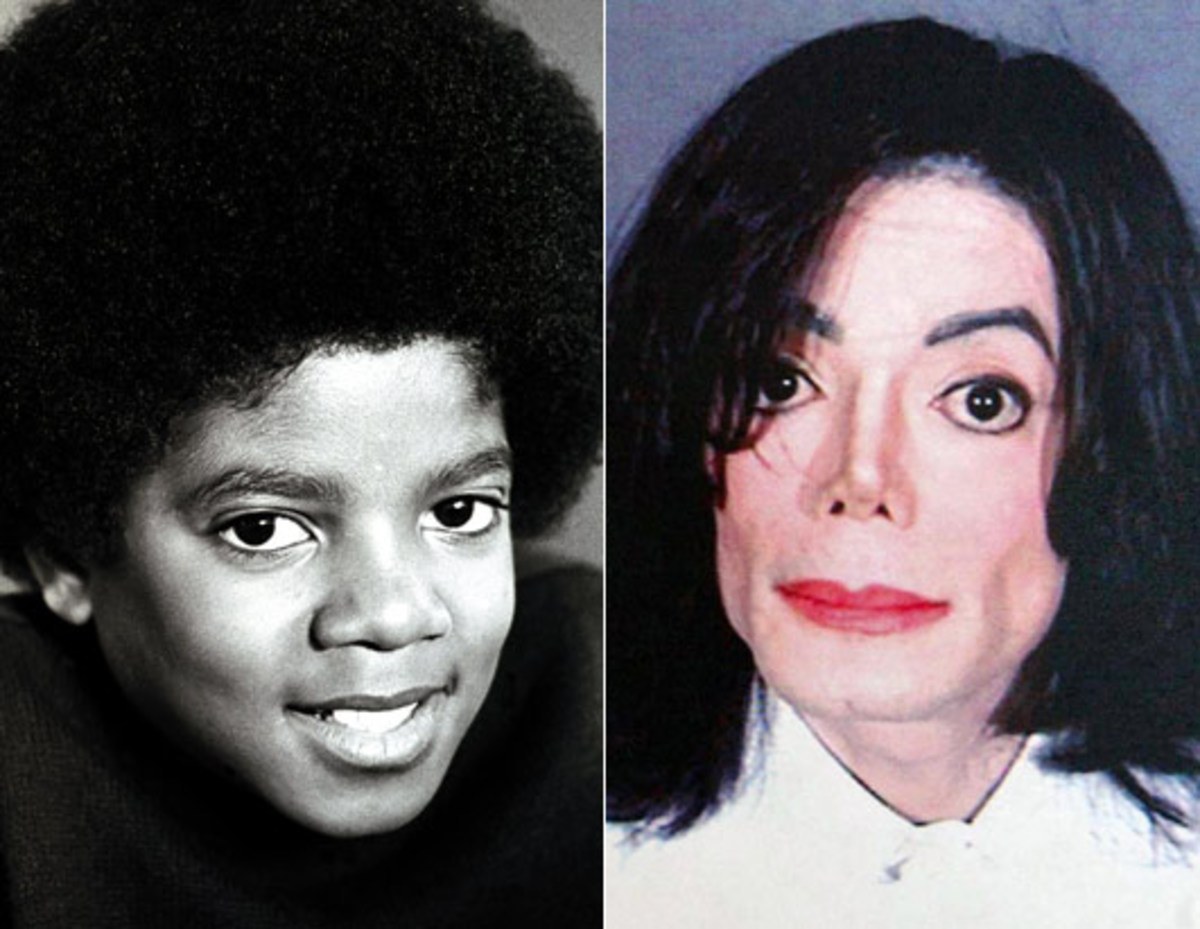

Over the course of more than a decade, Michael Jackson transformed from a handsome young man with typical African American features into a ghostly apparition of a human being. Some of the changes were casual and common, such as straightening his hair. Others were the product of sophisticated surgical and medical procedures; his skin became several shades paler, and his face underwent major reconstruction.

Over the course of more than a decade, Michael Jackson transformed from a handsome young man with typical African American features into a ghostly apparition of a human being. Some of the changes were casual and common, such as straightening his hair. Others were the product of sophisticated surgical and medical procedures; his skin became several shades paler, and his face underwent major reconstruction.

As stark as the changes were, perhaps even more jarring were Jackson’s public denials. His transformation was so severe and empirical that it was as plain as, well, the nose on his face. Yet he insisted on playing out some modern-day telling of “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” either minimizing or steadfastly denying all of it. In order to explain away the changes or claim that they had never even happened, Jackson repeatedly offered up alternate versions of reality that ranged from the plausible-but-highly-unlikely to the utterly ludicrous. He blamed the skin bleaching on treatments for vitiligo, a rare skin disorder. He denied altogether the radical changes to his facial structure, claiming his cheek bones had always been that way because his family had “Indian blood.”

It was equal parts bizarre and sad. But in some ways, perhaps the most disturbing aspect of it all were those among Jackson’s loyal fans who swallowed his story whole. Despite the irrefutability of it all, they refuted it. They parroted his narratives in lockstep, repeating his claims and avidly defending the King of Pop from any questions to the contrary.

Today we face a similar situation. But it’s not about a pop star’s face lift. Ludicrous denials of reality and bizarre make believe counter-narratives are now are now central to discourses about politics and the politicized pandemic. Read more »

by Rafaël Newman

One afternoon in the 1980s, when I was at grad school at a university in the northeastern United States, I went for coffee with a slightly senior colleague. A boisterous, opinionated, well-liked Brooklyn native, she was renowned (or notorious, depending on one’s philologico-political position) for applying the latest “French theory” to ancient poetry, for her general sensitivity to the dernier cri emanating from Paris by way of New Haven, and for her reputed personal allegiance to the same polyvalent libertinage attributed to some of the most celebrated authors of classical antiquity.

At a certain point in our conversation, as I expatiated on my own aspirations in the burgeoning world of destabilized narrative and fluid identity, she leaned in close to confide in me, half conspiratorially, half shame-facedly: “Don’t tell anyone, but I’m not a lesbian.”

Her secret was safe with me; but I was shocked.

I daresay that the men with whom I made music almost thirty years later, in a band known as The NewMen, would have had a similar reaction had they heard of my publication of a text bearing on our work together: if they were thus to have their half-spoken suspicions confirmed, that the person who had been passing himself off as an emanation of postmodern subculture, and a disaffected dropout from the groves of academe, was in fact a mole; not the real thing at all, not a flesh-and-blood proponent of the idiom but a desiccated reflector upon it; not a creator but a critic; not the guarantor of folk authenticity via his full bodily and spiritual presence but a neurotic fetishizer of generic typologies—in short, a eunuch in the harem, rather than the sultan himself. Read more »

by Varun Gauri

How should you respond to bullying? Common wisdom says fight back, or at least stand up for yourself, or else bullies — connoisseurs and lovers of power — will keep humiliating you, like Lucy snatching the football when Charlie Brown tried a kick. On the other hand, if you can’t risk a fight with the bully, or if you could win over influential bystanders, maybe you should simply go about your business, not fight back, go high when they go low.

That is the situation Democrats are in. At least since the mid 1990s, Republicans have been breaking long-accepted political norms, vilifying the opposition, and playing constitutional hardball. Gingrich Republicans bent House rules and impeached Bill Clinton. State legislators adopted extreme gerrymandering. More recently, Senate Republicans grabbed Supreme Court seats. Although Democrats have occasionally played hardball, as well, the polarization and norm-breaking have largely been asymmetric. For instance, while high-level elected Republicans subscribed to birtherism (the notion Obama wasn’t born in the United States and was an illegitimate president), there is no counterpart movement among elected Democrats.

It is true that Democrats have fought back and played a bit of hardball themselves, now and again, but these efforts have been been intermittent and half-hearted — breaking the filibuster for Supreme Court nominees but maintaining it otherwise, challenging the personal integrity of Supreme Court nominees but deferring once Justices serve on the bench. Why the partial response? Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Eric J. Weiner

In an ever-changing, incomprehensible world the masses had reached the point where they would, at the same time, believe everything and nothing, think that everything was possible and that nothing was true… The totalitarian mass leaders based their propaganda on the correct psychological assumption that…one could make people believe the most fantastic statements one day, and trust that if the next day they were given irrefutable proof of their falsehood, they would take refuge in cynicism; instead of deserting the leaders who had lied to them, they would protest that they had known all along that the statement was a lie and would admire the leaders for their superior tactical cleverness. –Hannah Arendt

In this oft-reprinted quote from Hannah Arendt’s seminal work The Origins of Totalitarianism, many 21st century readers, particularly those engaged in pro-democracy movements in the United States and abroad, see Donald Trump and the emergent totalitarian formation of Trumpism sewn piecemeal onto the template that she constructed whole cloth from Hitler and Stalin’s political regimes. Although Trump hasn’t yet matched the political power, penchant for violence, or historical significance of Hitler or Stalin, he has made clear his disdain for democracy and exhibits a desire and willingness to use his power and violence to undo its institutional structures. For readers who are encouraged by the emergence of Trumpism and excited by its promise to make America great again, which includes inciting nationalistic pride, putting America’s interests first ahead of global concerns, policing public school curriculum for progressive ideological biases, packing the courts with sympathetic ideologues, and using banal procedural rules to derail the spirit of democratic negotiation and compromise then her work may provide you a cautionary tale regarding the potential implications of delivering on those promises.

In this oft-reprinted quote from Hannah Arendt’s seminal work The Origins of Totalitarianism, many 21st century readers, particularly those engaged in pro-democracy movements in the United States and abroad, see Donald Trump and the emergent totalitarian formation of Trumpism sewn piecemeal onto the template that she constructed whole cloth from Hitler and Stalin’s political regimes. Although Trump hasn’t yet matched the political power, penchant for violence, or historical significance of Hitler or Stalin, he has made clear his disdain for democracy and exhibits a desire and willingness to use his power and violence to undo its institutional structures. For readers who are encouraged by the emergence of Trumpism and excited by its promise to make America great again, which includes inciting nationalistic pride, putting America’s interests first ahead of global concerns, policing public school curriculum for progressive ideological biases, packing the courts with sympathetic ideologues, and using banal procedural rules to derail the spirit of democratic negotiation and compromise then her work may provide you a cautionary tale regarding the potential implications of delivering on those promises.

For its critics, Trumpism’s thrust is transparently dystopian, its trajectory violent and oppressive, its appeal to national greatness cynical, and its outcome always tragic and bloody. They have also consistently underestimated Trump’s capacity for violence and his ability, like Vladimir Putin, to “leverage inscrutability.” But for Trumpists, the ethos of totalitarianism and the future it promises is not oppressive or frightening, but is empowering and liberating. Read more »

by Jeroen Bouterse

“Everyone feels it’s an unbearable thought, to be limited in time, – but what if you were spatially unlimited, would that not be […] as desolate as immortality? By Zeus, no one is ever depressed because they do not physically coincide with the universe, I at least have never heard a philosopher or poet about it”

I was reminded of this thought, expressed by a character in a novella by the Dutch writer Harry Mulisch,[1] when I read Tim Sommers’s reflections about death here on 3QuarksDaily. Sommers suggests a similar symmetry between time and space: building on the idea that we can think of ourselves as four-dimensional creatures, he wonders why we should care more about being temporally limited than about being spatially limited.

Sommers presents his case, not as a clinching argument that demonstrates that death ought to be nothing to us, but as a therapeutic move that could make it lose some of its sting, changing our perspective on it by showing it to be like something we already accept. I think that is a fair strategy, although in the end I find neither Mulisch’s (character’s) nor Sommers’s version of this symmetry argument convincing.

Mulisch’s point concerns the absurdity or inhumanity of the infinite. His analogy in this respect seems to be about our extension in space and time: the character voicing it suggests we would like to exist in more time, and we might even believe we would like to exist in all time. However, we do not have that same desire to encompass the entire universe spatially and this should give us pause about wanting to encompass it temporally. In Mulisch’s version, then, the spatial counterpart to living longer is taking up more space. What we value is being large temporally speaking, and the question is: Why we do not accept the symmetry with space? Read more »

by Sarah Firisen

My name is Sarah Firisen, and I’m 5ft 2 inches tall and work in software sales. But I’m also, or used to be, Bianca Zanetti, a 5ft 9 size 0 (which I’m also not), fashion designer and proprietor of a chain of stores, Fashion by B. No, I’m not bipolar. Bianca Zanetti is my Second Life avatar.

My name is Sarah Firisen, and I’m 5ft 2 inches tall and work in software sales. But I’m also, or used to be, Bianca Zanetti, a 5ft 9 size 0 (which I’m also not), fashion designer and proprietor of a chain of stores, Fashion by B. No, I’m not bipolar. Bianca Zanetti is my Second Life avatar.

My now ex-husband and I were very into Second Life around 14 years ago. Quickly, we realized an essential truth about the virtual world: much like the real world, it gets boring very fast without some kind of purpose. Yes, there was the initial amusement of learning how Second Life worked. We learned how to change our clothes, body shape, and hair. We learned how to control our avatars so we could fly. That was fun. We met a few people and made some friends. I’ve written before about the very real friendships that I made in my virtual life. But after a few weeks, we needed more. My ex had always been very interested in ancient Rome. He found an ancient Roman sim (themed digital plots of land), ROMA, and became involved with the community. He bought a toga and eventually became a senator. A real-life archaeologist created the sim, and it attracted a large group of ancient history buffs. They enthusiastically took on role-playing from the senate to gladiators to high priestesses at one of the temples. When I checked into ROMA for this piece, it seems like the sim still exists and has an active community.

U.S. dollars could be traded for the in-world Linden currency, and Second Life had a vibrant economy. Virtual commerce was wide-ranging, from new hairstyles to clothes to waterslides. But if you were so inclined, everything and anything in Second Life was buildable by users. Manipulating basic shapes and adding colors and textures, it was possible to create anything that an avatar could desire. A scripting language could be attached to the objects in the same way that Javascript can be attached to HTML objects. Back then, I was a software developer and became fascinated with building and scripting. But I needed a purpose to my building. So I started making clothes for myself and then started selling them. To do that, I required stores in which to sell my clothes and scripts to enable people to buy my outfits. Before I knew it, Fashion by B was a serious hobby. Read more »