by Eric J. Weiner

In an ever-changing, incomprehensible world the masses had reached the point where they would, at the same time, believe everything and nothing, think that everything was possible and that nothing was true… The totalitarian mass leaders based their propaganda on the correct psychological assumption that…one could make people believe the most fantastic statements one day, and trust that if the next day they were given irrefutable proof of their falsehood, they would take refuge in cynicism; instead of deserting the leaders who had lied to them, they would protest that they had known all along that the statement was a lie and would admire the leaders for their superior tactical cleverness. –Hannah Arendt

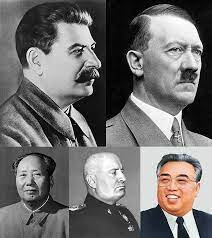

In this oft-reprinted quote from Hannah Arendt’s seminal work The Origins of Totalitarianism, many 21st century readers, particularly those engaged in pro-democracy movements in the United States and abroad, see Donald Trump and the emergent totalitarian formation of Trumpism sewn piecemeal onto the template that she constructed whole cloth from Hitler and Stalin’s political regimes. Although Trump hasn’t yet matched the political power, penchant for violence, or historical significance of Hitler or Stalin, he has made clear his disdain for democracy and exhibits a desire and willingness to use his power and violence to undo its institutional structures. For readers who are encouraged by the emergence of Trumpism and excited by its promise to make America great again, which includes inciting nationalistic pride, putting America’s interests first ahead of global concerns, policing public school curriculum for progressive ideological biases, packing the courts with sympathetic ideologues, and using banal procedural rules to derail the spirit of democratic negotiation and compromise then her work may provide you a cautionary tale regarding the potential implications of delivering on those promises.

In this oft-reprinted quote from Hannah Arendt’s seminal work The Origins of Totalitarianism, many 21st century readers, particularly those engaged in pro-democracy movements in the United States and abroad, see Donald Trump and the emergent totalitarian formation of Trumpism sewn piecemeal onto the template that she constructed whole cloth from Hitler and Stalin’s political regimes. Although Trump hasn’t yet matched the political power, penchant for violence, or historical significance of Hitler or Stalin, he has made clear his disdain for democracy and exhibits a desire and willingness to use his power and violence to undo its institutional structures. For readers who are encouraged by the emergence of Trumpism and excited by its promise to make America great again, which includes inciting nationalistic pride, putting America’s interests first ahead of global concerns, policing public school curriculum for progressive ideological biases, packing the courts with sympathetic ideologues, and using banal procedural rules to derail the spirit of democratic negotiation and compromise then her work may provide you a cautionary tale regarding the potential implications of delivering on those promises.

For its critics, Trumpism’s thrust is transparently dystopian, its trajectory violent and oppressive, its appeal to national greatness cynical, and its outcome always tragic and bloody. They have also consistently underestimated Trump’s capacity for violence and his ability, like Vladimir Putin, to “leverage inscrutability.” But for Trumpists, the ethos of totalitarianism and the future it promises is not oppressive or frightening, but is empowering and liberating.

Trumpism, unlike liberal democracy, promises safety, security, purity, and pride; it represents a viable alternative to a political system that has left them angry, fearful, insecure, guilty, and marginalized. Trumpism promises that all citizens will be released from the responsibilities of governing—what Erich Fromm described as “negative freedom”—while its supporters’ social, cultural, political, economic, and educational needs will be met. Equally important, they will, once again, be able to feel good about their nation, race, history, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, and religion without guilt or apology. Embracing what Putin calls a politics of “counter-enlightenment,” Trump represents himself and Trumpism as a corrective to what he sees as liberal democracy’s failure to defend the homeland from socialists, multicultural agitators, globalists, and dissident intellectuals. Like Putin’s United Russia party, Trumpists view liberal democracy as a “political arrangement that has outlived its purpose.”

It’s true that Trump/Trumpism’s supporters do not typically describe their emergent party or his leadership as totalitarian, even though they both embody many of its central organizing characteristics: Trumpism’s ethos and the future it imagines is anti-democratic; it demands from its constituencies an exchange of relative agency for the promise of comfort, safety, and security; it views compromise as weakness and domination as strength; truth is relative to its power as are its lies; it substitutes the rule of law for an ethic of domination; it requires schools to function as ideological state apparatuses; it uses violence and the threat of violence as a lever for social and political control; it manufactures propaganda through for-profit media to confuse, distort, and miseducate the public in the service of its own power; it is led and propelled by the charisma of an autocratic leader; it scapegoats a range of people who it sees as the cause of the country’s failings; it wants to reestablish racial and gender hierarchies; it substitutes nationalism for patriotism; and it criminalizes dissent. In an effort to deflect and deny its connection to these totalitarian characteristics, Trumpists portray themselves as victims of the “radical left” who they argue are trying to replace democracy with an authoritarian socialist government. Thus far, it seems to be an effective strategy, at least in terms of its ability to create a counter-hegemonic discourse within the GOP, conservative media, and in broadening Trumpism’s support more generally.

Not since the 1930s, writes Jill Lepore, has the hegemony of democracy in the United States been challenged as it is being challenged today from the totalitarian formation of Trumpism. Similar to the formation of past totalitarian regimes in Europe and South America, Trumpism has broad support from a diversity of people across the mainstream of society. Beyond the parade of characters we often see in the neoliberal media, Trumpism’s popularity reaches through the radical fringe and deep into the heart of the GOP. In addition to its “base” of neo-Nazi’s marching with tiki torches and chanting anti-Semitic slogans; Proud Boys and Oath Keepers looking to intimidate and do violence to anyone who gets in their way; or even those rank and file republicans who stormed the Capitol, Trumpism’s hegemonic power arises in large part from the support it gets from mainstream GOP, libertarian, and independent voters throughout the country. Trumpism’s widening demographic of support forces the utopic agenda of totalitarianism into the center of democratic life.

For those who scoff at the idea that there are parallel lessons to be gleaned from past totalitarian regimes, they should remember that only in retrospect do many of us look back and say with righteous indignation, there but for the grace of God go I. Indeed, Stalin, Castro, Chavez, and Mao maintained a grip on the left’s imaginary, even after bodies were discovered, books banned and burned, curriculum in the schools colonized, pedagogy surveilled, and dissidents imprisoned, murdered and exiled. Until he was discovered for being the genocidal maniac that he was, Hitler remained popular to many mainstream Germans, French, Austrians, and Poles who saw salvation and a radicalized hope in his soaring militaristic and anti-Semitic rhetoric. He promised German citizens a return to regional dominance and gave them permission to have pride in their culture and country. Others saw a powerful, truth-talking force of reform who was willing to help his allies rid themselves of Jews and others who challenged the cultural hegemony of white Christians in the region. He couldn’t have done what he did, nor could any of the other totalitarian leaders of the 20th century, without the implicit support of the mainstream citizenry and the military.

It’s important to remember that before the Holocaust trains became a symbol of terror and death globally, they were perceived by many Germans, Austrians, French, and Poles as a reasonable response to a real problem. Similarly, many Americans throughout US history, although not living under a formal totalitarian system, were nevertheless convinced that slavery, Jim Crow, Japanese internment camps, the “deculturalization” of Native Americans in Indian boarding schools, McCarthyism, and the criminalization of homosexuality were reasonable reactions to perceived threats. Rarely framed as articulations of totalitarian ideology, to the victims of these policies and initiatives, rationalistic appeals to Manifest Destiny and American Exceptionalism provided little comfort. In the passion of these historical moments, mainstream Americans, like their European and South American counterparts under different conditions, were consumed and blinded by dominant power’s utopic imaginary, making it difficult for them to recognize the unforeseen terror of totalitarian ideology that was hiding in plain sight.

Not all were so innocent, and what people knew, when they knew it, and what they did to stop the terror that was taking place under their noses are still essential questions. What we do know is that the utopic promises of totalitarian leaders rested not only on compelling propaganda and ruthless censorship, but also on the murdered, exiled, raped, tortured and imprisoned bodies/minds of the people that were designated a hindrance to the country’s imagined return to greatness. The utopic imaginary of past totalitarian regimes always demanded and rationalized a “cleansing,” removal, silencing, and erasure. We also know that there is never an end—a final solution—that would negate the need to cleanse, remove, silence and erase because the utopic imaginary of totalitarianism requires an endless supply of enemies, agitators, and dissidents. Its promises, as we now know, were only levers by which to concretize and maintain the absolute power of the leader and his regime by any means necessary.

As an articulation of past totalitarian regimes, Trumpism is a relatively blank slate upon which the fearful, insecure, nostalgic, righteous, and nationalistic can project their own fantasies of what a return to greatness will look like under Trump’s charismatic leadership. I believe this is why Trump/Trumpism continues to have such broad support across radically different constituencies. For its followers, the “post-modern” ambiguity of Trumpism allows them to imprint, map, project and transfer their own knowledge, experience, rage, and hope onto its articulation of totalitarian leadership and power. Trump/Trumpism will deliver them from the repressive terrors of “illiberal” democracy and into a future in which their group’s interests will be respected and protected from “the other” and all the dangers to freedom and opportunity they represent.

The most concrete move Trump makes in the service of Trumpism—and the crux of its power—is to provide different groups with different enemies for different reasons all the while positioning himself as the only person who can mitigate violence, enforce the peace, and determine what is just. The list of enemies is long and always growing: Black and brown people, the disabled, feminists, gay people, immigrants, Mexicans, the impoverished, China, liberals, socialists, “agitators,” the “liberal” media, Google, Facebook, Twitter, Apple, the New York Times, The Washington Post, Amazon, the U.S. postal service, higher education, public schools, history teachers, science, Palestinians, Muslims, Jews, “critical race theory,” ethnic studies, abortion rights advocates, Dr. Fauci, the “radical left,” “liberal” judges, transsexuals, and intellectuals are his main targets today. Once he has manufactured representations of these “enemies of the people,” his followers (i.e., the people) pick and choose which ones are most deserving of their rage, while ignoring those that might contradict or trouble their choices. From the pulpit of social media, Trump appoints himself judge, jury, and executioner.

Jews can ignore his anti-Semitic dog whistles and alignment with white supremacist movements because he gives them the divisive issue of Israel and the anti-Semitic threat of Palestinians and Muslims. His followers who would never think of themselves as racist or misogynistic rationalize their support on his representation of socialists and dissident intellectuals while ignoring his degrading comments about women and people of color. Evangelicals glam onto his support of Israel, anti-abortion, and homophobia while ignoring his profane behavior and language toward women and immigrants. Working-class white people are encouraged to ally themselves with wealthy whites even though their class and racial interests are more consistent with working-class people of color. Anti-government “vaxxers” demand that the government ban and/or regulate a woman’s decision to abort a fetus in her body, while demanding that the government has no right to mandate vaccinations during the COVID pandemic. Parents are encouraged to surveil and censor teachers and curriculum in their children’s schools for “anti-American” and “liberal” bias, while demanding that teachers and curriculum remain neutral. Etc., etc., etc. This creates a tapestry of contradictions that strengthens Trumpism while confusing the pro-democracy movement.

What adds to the frustration of pro-democracy movements in the United States and stymies their initiatives—in addition to liberal democracy and neoliberalism’s failure to deliver economic, food, health, and educational security to vast segments of the population—is Trump/Trumpism’s refusal to acknowledge its alignment with totalitarian ideology. Like Putin, Trump uses democracy as a veil to hide the totalitarian ethos of his party and leadership. Because of its public rejection of totalitarianism as a way to describe the party’s ethos and developing ideology, the leadership can condemn past totalitarian regimes—even assert that pro-democracy movements are themselves repressive—while, at the same time, advance a political agenda that is in line with totalitarianism’s essential principles. Standing behind other 21st century “standard-bearers of counter-enlightenment” like Putin, Viktor Orbán, and Kim Jong-un, Trump aspires to their levels of dictatorial power while using existing democratic institutions to elevate his standing and hollow-out democratic structures.

It is true and no small matter that liberal democracy in its uneasy partnership with neoliberalism has failed to provide the poor, the working-class, African-Americans, recent refugees and immigrants, women, and members of the LGBTQ community formidable levels of political capital. It is also inefficient, expensive, and frightening, or in Winston Churchill’s famous characterization from 1947, “the worst form of government except all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.” In its more radically utopic forms, it checks against power’s concretization and centralization while holding it accountable through elections, term limits, constitutional constraints, and the continuous participation of the people. Yet this is only true if, as Churchill continued, “there is the broad feeling…that the people should rule, continuously rule, and that public opinion, expressed by all constitutional means, should shape, guide, and control the actions of Ministers who are their servants and not their masters.”

In 2022, I am much less convinced than Churchill was in 1947 that there is a broad feeling in the United States that the people should continuously rule. Democracy only works if a large majority of the citizenry believes in the value of self-governance and learns the associative skills and habits of mind it demands. Once the idea of self-governance becomes suspect and undesirable to enough people then democracy’s hegemonic power will weaken and be replaced. Democracy’s only real promise to those constituencies of people who are suffering from the anomic implications of official power is its commitment to a process by which diverse people work together toward common goals. Outside of some abstract and contentious appeals to human nature, justice, and rights, it provides little guidance about what the outcomes of this process should be and offers no guarantees that participating in the process will get you everything that you want. Diverse democracies require high levels of emotional maturity, intellectual sophistication, and equitable relations of capital while totalitarianism, by contrast, is an infantilizing discourse unburdened by ethical constraints, the need to compromise, or the requirement for the people’s continuous participation in governance.

The Limits of Democratic Education

Helping to ensure the development and refinement of Trumpism’s utopic imaginary requires a combination of formal and informal education and schooling that must operate, as Antonio Gramsci explained, at the level of hegemony. From the public pedagogy of mass media and other cultural systems to the standardization of curriculum in schools, the utopic imaginary demands constant attention and institutional reinforcement to become and remain hegemonic. This might be why, in a recent interview with NPR about the possibility of a military-supported coup in the upcoming 2024 U.S. presidential election, Paul Eaton, a retired U.S. Army Major General and a senior adviser to VoteVets argues that civic literacy, liberal arts, and philosophy must be strategically weaponized in a national effort to fortify democracy’s waning hegemony. Is Major General Eaton’s assertion naïve? Has democracy’s hegemony been undone beyond the mitigating capacities of education and schooling? Are the people who still believe in the power of democratic education and the viability of democracy fighting a losing rearguard effort to preserve what little remains of democratic life?

Major General Easton is in good company in his appeal to curriculum and education as a bulwark against autocratic movements. From Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, George Washington, James Madison, Horace Mann, and John Dewey to Nancy Fraser, Henry Giroux, Gayatri Spivak, John Goodlad, Myles Horton, Noam Chomsky, and Chantal Mouffe, democracy’s success rests upon the power of society’s educational and cultural structures to enculturate and cultivate citizens’ habits of mind and body so that they are attuned to the specific demands of democratic life. Jeffrey Rosen writes, “The Framers themselves believed that the fate of the republic depended on an educated citizenry. Drawing again on his studies of ancient republics, which taught that broad education of citizens was the best security against ‘crafty and dangerous encroachments on the public liberty,’ Madison insisted that the rich should subsidize the education of the poor.”

Leaving aside the fact that supporters of totalitarian leaders, past and present, aren’t all uneducated and illiterate morons, the appeal to education as a bulwark against totalitarianism rests on a notion of education beyond, and in some cases, against schooling. It also depends upon a specific kind of constitutional education, one that involves a deep dive into the contentious concept and practice of critical thinking. But the core of the problem—and there are many—with educational appeals is that there is never a guarantee that people will come to the same or even the most reasonable conclusions about governing and power regardless of how “critical” or democratic their education might be. Standardize and democratize curriculum and pedagogy until the cows come home, there will never be a system of public education that openly and authentically supports free-thinking on one hand and guarantees ideological outcomes on the other.

For those writing about the relationship between education and democracy from a more “critical” perspective, there are other problems with the Madisonian appeal to a constitutional education funded by the wealthy. Madison’s suspicion of unreasonable and unleashed factions driven by self-interest and impulsive passions is suspect for its own quiet sexism, racism, and class elitism. Madison’s desire to control the “excesses of democracy” in an effort to save the republic from the mob is read as an attempt to solidify his own tribe’s standing at the top of the political hierarchy. Almost two-hundred years after Madison’s cautionary words, William F. Buckley argued a similar point in his debate with James Baldwin, asserting that the essential problem with racism and democracy wasn’t that black people couldn’t vote or had less access to voting than whites, but that too many poor, uneducated Southern white people could.

From a somewhat different perspective, the Trilateral Commission’s report, the “Crisis of Democracy (1975)”, warned that democratic governments were losing their hegemonic authority locally and abroad because of what they described as “excesses of democracy” by which they meant, according to Noam Chomsky, the work of groups like the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS); grassroots resistance to the Viet Nam war; grassroots advocacy and advancement of women’s rights through feminist movements; the advancement of civil rights coupled with the grassroots community work of the Black Panther Party; workers’ rights movements, unionization, and the strengthening of the growing popularity of socialist ideas; and gay rights particularly as it advanced violently out of the Stonewall rebellion. Advocates of radical or participatory democracy counter that the need to control the excesses of democracy through representative electoral structures, policing and militarization, and the standardization of curriculum and instruction in public schools continues to disenfranchise poor people, minorities, and others who question neoliberalism’s compatibility with democratic interests. And this is what constitutes the real threat to democracy then and now.

From the perspective of progressive, liberal and radical democratic educators, if democracy is to have a chance in the 21st century against the seductions of totalitarianism—if it is able to create a bulwark against what Madison described as unreasonable and impetuous factions “united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adversed to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community”—then the citizenry needs to be educated in a way that makes the utopic promises of democracy irresistible while simultaneously making totalitarianism’s promise of a mythical return to power, purity and greatness unconvincing. If democracy is to take root and thrive on a hegemonic level—that is, on a level that is deeply enfleshed in the dispositions, attitudes, knowledge, emotional reflexes, language, and “good” common sense of the citizenry—they argue that we must create political, cultural, and educational institutions and systems of thought that will support such a goal.

However important these ideas are for the development, maintenance and reproduction of democracy, they will not, at this point, protect us from the real and present danger that Trumpism represents. Education and schooling are effective long-term strategies of hegemony, but not as rearguard tactics of resistance. They will do little in the immediate future to hold back the totalitarian tide that is flooding local, state and national elections. “We’re taking action. We’re taking over school boards. We’re taking over the Republican Party with the precinct committee strategy. We’re taking over all the elections,” Steve Bannon proudly admits. From school boards, county commissions, and congress to mass media, the courts, and the presidency, the age of democracy in the United States is quickly being replaced by a totalitarian network of determined individuals and well-funded organizations who no longer see the value of democracy—beyond its ability to get them elected into positions of influence and power—for themselves, their families, communities, states, or country.

Once enough anti-democratic representatives are elected into offices at various levels of influence, they can then use the authority of their office to undo the democratic systems that put them there in the first place. Once enough conservative, “anti-democratic” judges are appointed to the bench, then the constitutional constraints that have helped keep totalitarian forces out of democratic life will be undone. Once enough military leaders accept that totalitarianism is the only realistic way to control the forces of socialism, then the foundations of democratic government will begin to crumble. When enough parents decide that censoring books and curriculum in their children’s schools is in the interest of freedom, then education can no longer be a weapon against the rising tide of totalitarianism.

Harvard political science professor Daniel Ziblatt points out that this is no longer a fight between conservatives and liberals, occasionally provoked and troubled by the radical ideas of dissident intellectuals: It is now a struggle over the hegemony of opposing ideological formations. This struggle marks the beginning of a “cold” civil war in the United States. What the pro-totalitarian movement in the United States understands that the pro-democracy movement does not is that they are playing a zero-sum game. Whether the pro-democracy movement in the United States can learn the rules of this new game as they play it remains to be seen. But it is probably a bit too late for lessons in civic literacy, liberal arts, and philosophy to, in former Vice President Dick Cheney’s words, “restore the Constitution” or protect democracy against the insurgency of totalitarianism.

A more effective strategy, and one that worked to stave off the formation of authoritarianism in the United States in the 1930s, would be to begin a nation-wide debate about Democracy vs. Totalitarianism. Like in the grassroots democracy debates that Jill Lepore chronicles, it is past due for this kind of educative initiative in 2022. Democracy must get in the ring with totalitarianism once again and, like any good fight worth watching, the outcome is far from certain. It is imperative that these types of debates and critical dialogues begin to take place in diverse communities, towns, and across digital media platforms. It’s possible that it’s too late and these imagined spaces would devolve into violence; be shut down by the totalitarian forces that are already rooted in U.S. soil, locked and loaded; or never sanctioned in the first place. These kinds of forums and debates can only occur before totalitarian groups and social networks take deep root. Once they do, then honest debates about which system is more desirable becomes moot since the debates themselves are an example of democratic practice and proof that totalitarianism hasn’t yet been victorious.

Once the anti-democratic formations are rooted, it is unlikely that they will be challenged through sanctioned educational initiatives. From a political perspective, established totalitarian systems cannot be removed through formal democratic channels. If past and present totalitarian regimes are instructive, autocratic rulers with the support of their followers and the military, will use all their power to prevent these initiatives from taking place. They will also clamp down on political dissent through the usual strategies of repression. With the exception of the Velvet Revolution of 1989, there are few examples of non-violent, pro-democracy movements that were able to structurally unsettle established autocracies. However daunting, frightening, and hard it is to confront the rising popularity of totalitarianism, it is easier and better, as history has shown, to stop it before it gets too much traction.

Are we too late? According to Harvard University political scientists Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt, authors of How Democracies Die, the writing is on the wall. Will pro-democracy movements in the United States and abroad rise to the challenge? Or will they continue to play the game as if the rules of constitutional democracy still constrain the behaviors and attitudes of their opponents? Will SCOTUS keep itself grounded in the democratic spirit of the Constitution or has it already sacrificed its legitimacy to political punditry? Will schools teach against the grain of censoring authorities or have they already conceded their pedagogical autonomy to totalitarian-leaning state interests? Will citizens–liberals and conservatives–who still value democracy have the courage, wherewithal, and social capital to rise up in force against those who are trying to undermine and destroy it? Will universities and public schools recommit themselves to critical thinking across the disciplines and become alternative public spheres of democratic teaching and learning? The fact that these questions still remain, to some degree, unanswered suggests that hope for democracy’s survival in the United States is not lost.