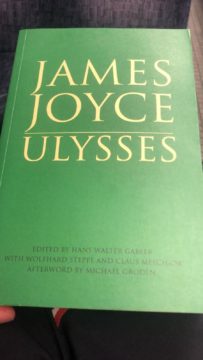

by David J. Lobina

A testy title for an article about James Joyce in this centenary year of the publication of Ulysses, but all the more pertinent for that, especially in the context of this series on Language and Thought (and I don’t really mean that he was wrong, actually). After all, last month I brought up the role of “talking to ourselves” in reasoning and decision-making – to think – and the narrative technique of interior monologue, amply used in Ulysses, is precisely meant to depict the phenomenon I was dealing with – inner speech, in the parlance of philosophers and psychologists. Not to be confused with the stream-of-consciousness technique, though they are related, the interior-monologue technique is a linguistic rendering of a character’s thoughts, whereas a stream of consciousness may include the character’s perceptions and impressions (visual, aural, what have you) in addition to their inner speech, and it typically comes from the pen of a narrator rather than directly from the mind of a character as is the case in inner speech.[i]

As a case in point:

—Is it your view, then, that she was not faithful to the poet?

Alarmed face asks me. Why did he come? Courtesy or an inward light?

—Where there is a reconciliation, Stephen said, there must have been first a sundering.

At first sight the presence of interior monologue in this exchange (signposted by my italics, here and henceforth), as imagined by Joyce in the Ulysses, seems a plausible rendering of the thoughts Stephen Dedalus was having at the time. Is it psychologically plausible, though? I don’t mean whether Stephen was really having such thoughts – he did, Joyce wrote so. What I mean is whether Stephen was actually verbalising these thoughts to himself in inner speech as he was having them. Read more »

In both ISI and DSE there was one problem I faced in my research that was something I did not fully anticipate before. Some of the major international journals had a submission fee for research papers which was equivalent to something that would exhaust most of my Indian monthly salary. In the US authors mostly charged the fee to their research grants, which was not a way out for me. I once wrote about this to the Executive Committee of the American Economic Association (AEA), and suggested that for their journals they should have a lower rate for authors from low-income countries. I got a reply, saying that after careful consideration in their Committee meeting they had decided against my suggestion. Their rationale was a typical one for believers in perfect markets: since an article in an AEA journal was likely to raise significantly the expected lifetime earnings of an author, the latter should be able to finance it. (I visualized the dour face of an Indian public bank loan officer trying to comprehend this).

In both ISI and DSE there was one problem I faced in my research that was something I did not fully anticipate before. Some of the major international journals had a submission fee for research papers which was equivalent to something that would exhaust most of my Indian monthly salary. In the US authors mostly charged the fee to their research grants, which was not a way out for me. I once wrote about this to the Executive Committee of the American Economic Association (AEA), and suggested that for their journals they should have a lower rate for authors from low-income countries. I got a reply, saying that after careful consideration in their Committee meeting they had decided against my suggestion. Their rationale was a typical one for believers in perfect markets: since an article in an AEA journal was likely to raise significantly the expected lifetime earnings of an author, the latter should be able to finance it. (I visualized the dour face of an Indian public bank loan officer trying to comprehend this). Vladimir Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine is clearly a historically momentous event, already appearing to cause a seismic shift in the geopolitical landscape. What the long-term consequences will be are hard to say. The most obvious losers are the millions of Ukrainians–killed, injured, bereft, and displaced–who are the immediate victims of Putin’s onslaught. The most likely winner will probably be China, on whom Russia is suddenly much more economically dependent due to the sanctions imposed by the West, and who can therefore now expect Putin to dance to whatever tune it whistles.

Vladimir Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine is clearly a historically momentous event, already appearing to cause a seismic shift in the geopolitical landscape. What the long-term consequences will be are hard to say. The most obvious losers are the millions of Ukrainians–killed, injured, bereft, and displaced–who are the immediate victims of Putin’s onslaught. The most likely winner will probably be China, on whom Russia is suddenly much more economically dependent due to the sanctions imposed by the West, and who can therefore now expect Putin to dance to whatever tune it whistles. The Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle (Workshop of Potential Literature), Oulipo for short, is the name of a group of primarily French writers, mathematicians, and academics that explores the use of mathematical and quasi-mathematical techniques in literature. Don’t let this description scare you. The results are often amusing, strange, and thought-provoking.

The Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle (Workshop of Potential Literature), Oulipo for short, is the name of a group of primarily French writers, mathematicians, and academics that explores the use of mathematical and quasi-mathematical techniques in literature. Don’t let this description scare you. The results are often amusing, strange, and thought-provoking. Despite living here for nearly three years now, I have no social life to speak of. At risk of sounding self-loathing, a not insignificant part of the problem is probably just me: I’m not the most social person in the world. Plus, there’s the pandemic, which hit six months after we moved here. But I don’t think it’s just me, or even just the pandemic. An awful lot of people who moved here as adults, decades ago, and are much nicer and more sociable than I am, have said the same thing: making friends in Toronto is hard.

Despite living here for nearly three years now, I have no social life to speak of. At risk of sounding self-loathing, a not insignificant part of the problem is probably just me: I’m not the most social person in the world. Plus, there’s the pandemic, which hit six months after we moved here. But I don’t think it’s just me, or even just the pandemic. An awful lot of people who moved here as adults, decades ago, and are much nicer and more sociable than I am, have said the same thing: making friends in Toronto is hard.

Sughra Raza. Self-portrait With Trees. Seattle, February, 2022.

Sughra Raza. Self-portrait With Trees. Seattle, February, 2022.

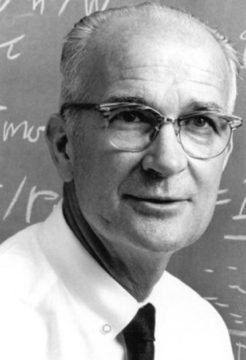

On 4 October 1957, in my mind’s eye, I was playing alone in the back yard when the radio in the breezeway broadcast a special news bulletin that changed my life. We had moved from Chicago to Minneapolis in 1951 and my parents had bought a recently built house on a dead-end street in a relatively cheap residential area out near the airport. The house was built in the modern suburban style that people called a ranch-style bungalow and its most interesting post-war feature was the breezeway, a screened-in patio attached to the house. The screens that kept flies and mosquitos at bay in warm weather were swapped for glass panels when the weather turned cold and we changed our window screens for storm widows.

On 4 October 1957, in my mind’s eye, I was playing alone in the back yard when the radio in the breezeway broadcast a special news bulletin that changed my life. We had moved from Chicago to Minneapolis in 1951 and my parents had bought a recently built house on a dead-end street in a relatively cheap residential area out near the airport. The house was built in the modern suburban style that people called a ranch-style bungalow and its most interesting post-war feature was the breezeway, a screened-in patio attached to the house. The screens that kept flies and mosquitos at bay in warm weather were swapped for glass panels when the weather turned cold and we changed our window screens for storm widows.

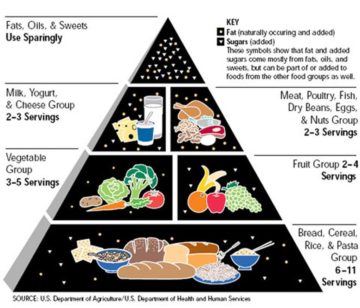

We have many choices when deciding what to eat. For most of human history, however, there has likely been little to no choice at all: people ate what was available to them or what their culture led them to eat. Now things are not so simple. As I mentioned in

We have many choices when deciding what to eat. For most of human history, however, there has likely been little to no choice at all: people ate what was available to them or what their culture led them to eat. Now things are not so simple. As I mentioned in