by Sarah Firisen

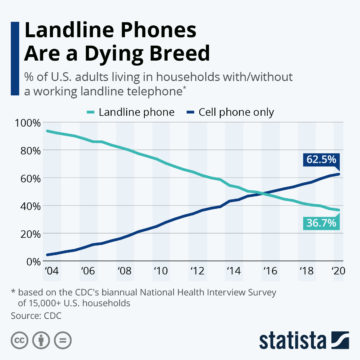

I began the process of cutting the cord when I moved back to NYC from upstate NY 10 years ago. I didn’t sign up for cable or home phone service. Instead, I had a mobile phone and Netflix, Amazon Prime Video, and Hulu. It felt liberating. Periodically, Verizon FIOS (through whom I had my home internet service) would contact me to offer me a “great deal” on a package that would usually include a home phone line and some sort of cable package, and I would happily tell them where to shove it. I never regretted this decision, and I know I’m far from the only person to do some version of this over the last decade.

My mobile phone service has been through my employer for the last few years, but I recently decided I wanted to take my number out of the corporate plan and pay for my mobile service. Our mobile phone numbers have become an increasing part of our identities. I remember the early days of mobile phone numbers when New Yorkers became anxious that the “prestigious” 917 area code numbers were running out. I have a 518 area code because I lived in upstate New York when I first got a mobile number. But that area code no longer has any connection to my physical location; I’m domiciled in Florida and spend most of my time in the Caribbean. But it is the number that all my online accounts are tied to, which connects me to every aspect of how I manage my life these days. I could change it, but it would be painful. Read more »

Lanchester’s square law was formulated during World War I and has been taught in the military ever since. It is marginally relevant to the war in Ukraine, particularly the balance between the quantity and quality of the two armies’ weapon systems.

Lanchester’s square law was formulated during World War I and has been taught in the military ever since. It is marginally relevant to the war in Ukraine, particularly the balance between the quantity and quality of the two armies’ weapon systems.

I regret not having children younger. Like, much younger. I was thirty-six when my first child, now four, was born; thirty-eight when my second was born. I wish I had done it when I was in my early twenties. This is an unpopular perspective. I know this because when I’ve raised this feeling with friends, many of whom had children similarly late in life, I’ve been met with a strong resistance. It’s not just that they don’t share my feelings, that their experience of having children later in life is different to mine, it’s that they somehow mind me feeling the way that I do. They think that I am wrong – mistaken – to feel this way. It upsets them.

I regret not having children younger. Like, much younger. I was thirty-six when my first child, now four, was born; thirty-eight when my second was born. I wish I had done it when I was in my early twenties. This is an unpopular perspective. I know this because when I’ve raised this feeling with friends, many of whom had children similarly late in life, I’ve been met with a strong resistance. It’s not just that they don’t share my feelings, that their experience of having children later in life is different to mine, it’s that they somehow mind me feeling the way that I do. They think that I am wrong – mistaken – to feel this way. It upsets them.  The dandelion is thousands of miles from home. It has been in America learning about the world beyond and perhaps it wants to return. It has lived thousands of sad lives. Finally after 300 years, a seed clings to an old man’s jacket as he boards a plane, and happens to land in a small patch of dirt right by the Charles de Gaulle airport; the dandelion is welcomed home graciously, and they share the stories of what has happened in its absence. They notice little differences to him. He has mutated slightly; the increased sun in America has made his petals more yellow; the lawn mowers have made him shorter; the pesticides have made him stronger. They don’t talk to him about the sun or the lawn mowers or the pesticides, though. They talk about their shared home in France.

The dandelion is thousands of miles from home. It has been in America learning about the world beyond and perhaps it wants to return. It has lived thousands of sad lives. Finally after 300 years, a seed clings to an old man’s jacket as he boards a plane, and happens to land in a small patch of dirt right by the Charles de Gaulle airport; the dandelion is welcomed home graciously, and they share the stories of what has happened in its absence. They notice little differences to him. He has mutated slightly; the increased sun in America has made his petals more yellow; the lawn mowers have made him shorter; the pesticides have made him stronger. They don’t talk to him about the sun or the lawn mowers or the pesticides, though. They talk about their shared home in France.

Halfway through a pilgrimage, it’s a good thing to remember why you’re on it – where you hope it’s taking you. I’m following a plan to consider the strangely numerous churches of this little Portland neighborhood, just a half-mile square but crowded with varieties of religiosity.

Halfway through a pilgrimage, it’s a good thing to remember why you’re on it – where you hope it’s taking you. I’m following a plan to consider the strangely numerous churches of this little Portland neighborhood, just a half-mile square but crowded with varieties of religiosity.

Twitter is toxic, suggests autocomplete; Twitter is an echo chamber, or at best a waste of time. Twitter is a hotbed of political factionalism. Twitter can be a frightening place for people who are harassed or threatened, and it may become more so when a recently announced takeover is complete. The bullying and misinformation and political threat are all real, and they’ve been central to recent discussions about the takeover. But Twitter is a big place, and some of us are there mainly for things we love. Birds, for example, and poems.

Twitter is toxic, suggests autocomplete; Twitter is an echo chamber, or at best a waste of time. Twitter is a hotbed of political factionalism. Twitter can be a frightening place for people who are harassed or threatened, and it may become more so when a recently announced takeover is complete. The bullying and misinformation and political threat are all real, and they’ve been central to recent discussions about the takeover. But Twitter is a big place, and some of us are there mainly for things we love. Birds, for example, and poems.