by Fabio Tollon

We often make bad choices. We eat sugary foods too often, we don’t save enough for retirement, and we don’t get enough exercise. Helpfully, the modern world presents us with a plethora of ways to overcome these weaknesses of our will. We can use calorie tracking applications to monitor our sugar intake, we can automatically have funds taken from our account to fund retirement schemes, and we can use our phones and smartwatches to make us feel bad if we haven’t exercised in a while. All of these might seem innocuous and relatively unproblematic: what is wrong with using technology to try and be a better, healthier, version of yourself?

Well, let’s first take a step back. In all of these cases what are we trying to achieve? Intuitively, the story might go something like this: we want to be better and healthier, and we know we often struggle to do so. We are weak when faced with the Snickers bar, and we can’t be bothered to exercise when we could be binging The Office for the third time this month. What seems to be happening is that our desire to do what all things considered we think is best is rendered moot by the temptation in front of us. Therefore, we try to introduce changes to our behaviour that might help us overcome these temptations. We might always eat before going shopping, reducing the chances that we are tempted by chocolate, or we could exercise first thing in the morning, before our brains have time to process what a godawful idea that might be. These solutions are based on the idea that we sometimes, predictably, act in ways that are against our own self-interest. That is to say, we are sometimes irrational, and these “solutions” are ways of getting our present selves to do what we determine is in the best interests of future selves. Key to this, though, is we as individuals get to intentionally determine the scope and content of these interventions. What happens when third parties, such as governments and corporations, try to do something similar?

Attempts at this kind of intervention are often collected under the label “nudging”, which is a term used to pick out a particular kind of behavioural modification program. The term was popularized by the now famous book, Nudge, in which Thaler and Sunstein argue in favour of “libertarian-paternalism”. Read more »

There are two kinds of people in this world: those who find basements scary and those who find attics scary. I suppose there might be some folks (bless their hearts) who are disturbed by both, like those ethereal creatures with one blue eye and one brown. I refuse to countenance the idea of people who have no feelings of unease in either space. To be that well-adjusted, that free from inchoate fear, that grounded in the solid objects of reality—I draw back in horror at the thought. We will leave these hale and pragmatic types to their smoothies and their 401Ks and godspeed to them.

There are two kinds of people in this world: those who find basements scary and those who find attics scary. I suppose there might be some folks (bless their hearts) who are disturbed by both, like those ethereal creatures with one blue eye and one brown. I refuse to countenance the idea of people who have no feelings of unease in either space. To be that well-adjusted, that free from inchoate fear, that grounded in the solid objects of reality—I draw back in horror at the thought. We will leave these hale and pragmatic types to their smoothies and their 401Ks and godspeed to them.

I find Sue Hubbard’s writings to be an invitation to feel sorrowful. And therefore a beckoning towards a search for beauty, an attempt at forgiveness and redemption and reckoning; a belief in the possibility of joy.

I find Sue Hubbard’s writings to be an invitation to feel sorrowful. And therefore a beckoning towards a search for beauty, an attempt at forgiveness and redemption and reckoning; a belief in the possibility of joy. June 4 early morning we took a taxi from Friendship Hotel to the Beijing airport, oblivious of the dreadful happenings in Tiananmen Square the previous night. I remember the taxi driver in his almost non-existent English tried to tell us that ‘something’ (he was not sure what) had happened in the night in the Square, traffic was not allowed to go in that direction. By the time we reached Shanghai, our hosts who came to receive us knew. Of course, they could not know it from radio or TV, as there was a news blackout. These were days before internet, but cross-country fax messages were still active. Beijing to Shanghai messages were blocked, but people in Beijing were sending fax messages to their friends and relatives in Los Angeles, and the latter were sending messages to Shanghai.

June 4 early morning we took a taxi from Friendship Hotel to the Beijing airport, oblivious of the dreadful happenings in Tiananmen Square the previous night. I remember the taxi driver in his almost non-existent English tried to tell us that ‘something’ (he was not sure what) had happened in the night in the Square, traffic was not allowed to go in that direction. By the time we reached Shanghai, our hosts who came to receive us knew. Of course, they could not know it from radio or TV, as there was a news blackout. These were days before internet, but cross-country fax messages were still active. Beijing to Shanghai messages were blocked, but people in Beijing were sending fax messages to their friends and relatives in Los Angeles, and the latter were sending messages to Shanghai.

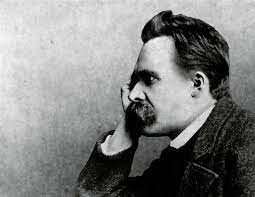

Friedrich Nietzsche is my “desert island philosopher.” Guests, or “castaways” on BBC Radio 4’s long running program “Desert Island Discs” are allowed to take to their desert island, in addition to eight pieces of music, a text of religious or philosophical significance. Many accept the bible as the default option. For me, the choice is a no brainer: I’d take the works of Nietzsche.

Friedrich Nietzsche is my “desert island philosopher.” Guests, or “castaways” on BBC Radio 4’s long running program “Desert Island Discs” are allowed to take to their desert island, in addition to eight pieces of music, a text of religious or philosophical significance. Many accept the bible as the default option. For me, the choice is a no brainer: I’d take the works of Nietzsche.

Leandro Erlich. “BÂTIMENT”, 2004, La Nuit Blanche, Paris, France.

Leandro Erlich. “BÂTIMENT”, 2004, La Nuit Blanche, Paris, France.

Language has an important role to play in national identity. One only has to think about the

Language has an important role to play in national identity. One only has to think about the

I’m not sure anyone has ever figured out how to write about music. This is a dangerous statement to make, and I’m sure readers will be quick to point out writers who have been able to capture something as intangible as sound via the written word. This would be a happy result of this article, and I welcome any and all suggestions. I should also say that I don’t mean there are no good music writers; there are, and I have certain writers I follow and read. But the question of how to write about music remains a tricky one.

I’m not sure anyone has ever figured out how to write about music. This is a dangerous statement to make, and I’m sure readers will be quick to point out writers who have been able to capture something as intangible as sound via the written word. This would be a happy result of this article, and I welcome any and all suggestions. I should also say that I don’t mean there are no good music writers; there are, and I have certain writers I follow and read. But the question of how to write about music remains a tricky one.

I got an incredible break when I was thirteen. We moved to Seattle and I entered public school in the sixth grade, after five years of Catholic education. The impact of the change in fortune was all the greater since I had no particular expectations, a good example of the principle that you can never know when things are about to change for the better. It was not just that my least favorite subject, religion, was no longer on the curriculum–that was the least of it. My new school exuded a different mood, much more open, so different to the reform school atmosphere I had become accustomed to. My life began to feel truly blessed.

I got an incredible break when I was thirteen. We moved to Seattle and I entered public school in the sixth grade, after five years of Catholic education. The impact of the change in fortune was all the greater since I had no particular expectations, a good example of the principle that you can never know when things are about to change for the better. It was not just that my least favorite subject, religion, was no longer on the curriculum–that was the least of it. My new school exuded a different mood, much more open, so different to the reform school atmosphere I had become accustomed to. My life began to feel truly blessed.