by Bill Benzon

11th Street Lilies: That’s a kind of photograph that exemplifies an urban pastoral sensibility. Loosely speaking it depicts an urban setting, but one that evokes a pastoral mood. In this case the photograph is dominated by the lilies in the foreground, which are in a flowerbed in a median strip running for several blocks on 11th street in Hoboken, New Jersey, where I currently live. It is a residential area, with two and three-story row houses and one or three small low-rise apartment buildings. While the flower bed is obvious enough when you walk the street, it dominates this photograph because I chose to make it so.

* * * * *

It was in graduate school, I believe, that I heard someone refer to Hart Crane as a poet of the “urban pastoral,” referring, I believe to his collection “The Bridge” – which I’ve not read. That was the first time I heard the phrase, “urban pastoral,” and it has stuck in my mind. But the phrase disappeared from view until 2004 when I began wandering my Jersey City neighborhood, camera in hand, in search of wild graffiti.

I photographed the graffiti, of course – lots of it – but that’s not all. I photographed other things as well, close-ups of bees and flowers, panoramas of this or that neighborhood view, of the Manhattan skyline from Jersey City, and – cliche of cliches – sunrises and sunsets. Thus on October, 1, 2007, ago I blogged “This Jersey City My Prison,” in which I set Coleridge’s “This Lime-Tree Bower My Prison” amid photographs taken in Jersey City. I have since reset the poem with photos I’ve taken in Hoboken. Read more »

I recently started a new job. The process of looking and interviewing for this job was unlike any other I’ve been through because I now live on the Caribbean island of Grenada. I moved here during the height of the pandemic when everyone was working from home. When I told my plans to the company I was working for then, their only comment was that I needed to stay domiciled in the US, which I have. But now that we’ve all gone back to some kind of post-COVID normalcy (even if variants are still coming at us hard and fast), I wasn’t sure how to approach a new company with my slightly unusual living situation. My initial thoughts were that I get through a first interview before bringing it up, but that seemed not only disingenuous but also pointless; they were going to have a problem with it, or they weren’t. Putting off the reveal was just a waste of everyone’s time. And so, I mostly led with this news. Amazingly, no one cared.

I recently started a new job. The process of looking and interviewing for this job was unlike any other I’ve been through because I now live on the Caribbean island of Grenada. I moved here during the height of the pandemic when everyone was working from home. When I told my plans to the company I was working for then, their only comment was that I needed to stay domiciled in the US, which I have. But now that we’ve all gone back to some kind of post-COVID normalcy (even if variants are still coming at us hard and fast), I wasn’t sure how to approach a new company with my slightly unusual living situation. My initial thoughts were that I get through a first interview before bringing it up, but that seemed not only disingenuous but also pointless; they were going to have a problem with it, or they weren’t. Putting off the reveal was just a waste of everyone’s time. And so, I mostly led with this news. Amazingly, no one cared.  In the early 1990’s I was a visiting fellow at St Catherine’s College and an academic visitor at Nuffield College in Oxford. At Nuffield College at that time two friends from my Cambridge student days were Fellows, Jim Mirrlees and Christopher Bliss. (I think Jim was mostly away during my visit, and graciously asked me to use his large office at Nuffield). The other person I used to see there off and on was Tony Atkinson who became the Warden of Nuffield shortly afterward. I knew Tony since our student days in Cambridge. Like me he also moved from one Cambridge to the other, to MIT, roughly around the same time. Both of us were heavily influenced by our teacher James Meade, though Tony never did a Ph.D. (as used to be the old British tradition—neither James Meade nor Joan Robinson had a Ph.D.) Tony did not follow Meade in the latter’s work on international trade, as I did, but in other respects he broadly followed on the footsteps of Meade, apart from sharing Meade’s personal characteristics of modesty, decency and a positive vision of the future. Tony was certainly among the best economists of my generation, with pioneering work on inequality, poverty, public policies, redistributive taxation, and welfare. He was also an advocate of Universal Basic Income. I had co-authored a chapter for the Handbook of Income Distribution that he co-edited with François Bourguignon, a French development economist friend of mine.

In the early 1990’s I was a visiting fellow at St Catherine’s College and an academic visitor at Nuffield College in Oxford. At Nuffield College at that time two friends from my Cambridge student days were Fellows, Jim Mirrlees and Christopher Bliss. (I think Jim was mostly away during my visit, and graciously asked me to use his large office at Nuffield). The other person I used to see there off and on was Tony Atkinson who became the Warden of Nuffield shortly afterward. I knew Tony since our student days in Cambridge. Like me he also moved from one Cambridge to the other, to MIT, roughly around the same time. Both of us were heavily influenced by our teacher James Meade, though Tony never did a Ph.D. (as used to be the old British tradition—neither James Meade nor Joan Robinson had a Ph.D.) Tony did not follow Meade in the latter’s work on international trade, as I did, but in other respects he broadly followed on the footsteps of Meade, apart from sharing Meade’s personal characteristics of modesty, decency and a positive vision of the future. Tony was certainly among the best economists of my generation, with pioneering work on inequality, poverty, public policies, redistributive taxation, and welfare. He was also an advocate of Universal Basic Income. I had co-authored a chapter for the Handbook of Income Distribution that he co-edited with François Bourguignon, a French development economist friend of mine.

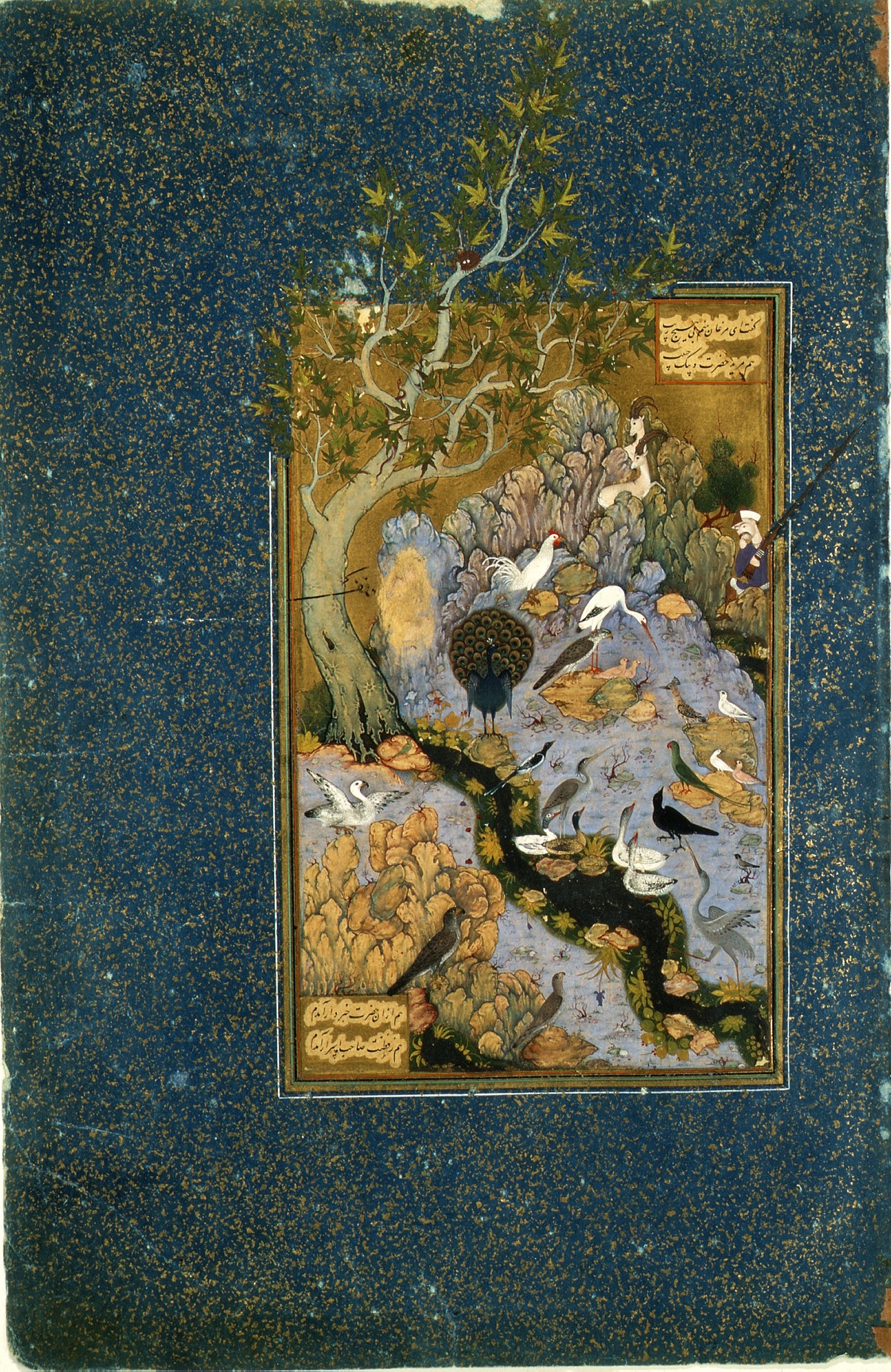

Habiballah of Sava. Concourse of The Birds, ca. 1600

Habiballah of Sava. Concourse of The Birds, ca. 1600

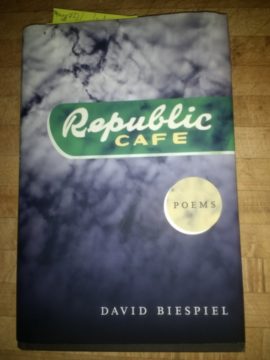

We sit in David Biespiel’s Republic Café: all of us together in the public space of democracy. It appeared in 2019, as American fascism made its perennial strut, less disguised than usual. At that point we’d endured two years of it. Lies spewed from the Leader’s mouth like flies from an open sewer, his followers enacting Hannah Arendt’s crisp formulation:

We sit in David Biespiel’s Republic Café: all of us together in the public space of democracy. It appeared in 2019, as American fascism made its perennial strut, less disguised than usual. At that point we’d endured two years of it. Lies spewed from the Leader’s mouth like flies from an open sewer, his followers enacting Hannah Arendt’s crisp formulation:

Nah. Let’s talk about our brains. The neocortex is where all our fancy thinking takes place. The neocortex wraps around the core of our brain, and if you could carefully unwrap it and lay it flat it would be about the size of a dinner napkin, and about 3 millimeters thick. The neocortex consists of 150,000 cortical columns, which we might think of as separate processing units involving hundreds of thousands of neurons. According to research at Jeff Hawkins’ company Numenta (and as explained in his fascinating recent book,

Nah. Let’s talk about our brains. The neocortex is where all our fancy thinking takes place. The neocortex wraps around the core of our brain, and if you could carefully unwrap it and lay it flat it would be about the size of a dinner napkin, and about 3 millimeters thick. The neocortex consists of 150,000 cortical columns, which we might think of as separate processing units involving hundreds of thousands of neurons. According to research at Jeff Hawkins’ company Numenta (and as explained in his fascinating recent book,  I assume that if your eye was drawn to this essay, then you are also troubled by feelings of rage. But I don’t want to be presumptuous—there are other reasons to read an essay that promises to tell you what to do with your anger. Maybe you think I have an agenda. Perhaps you have formed an idea of what my rage is about, and you disagree with that figment, and you are hate-reading these words right now, waiting for me to reveal the source of my own rage so that you can write a nasty comment at the end of this post or troll me on social media or try to cancel me or dox me or incite violence against me or come to my house and sneak onto my porch and stare balefully into my front windows or throw an egg at my car or trample deliberately on the ox-eye sunflowers that are bursting around my mailbox or put a bomb in my mailbox or disagree with me strenuously in your heart. There is a wide range of potential negative responses, and I don’t have time to list them all. The point here is that one must contend with them, and that is another reason to feel rage.

I assume that if your eye was drawn to this essay, then you are also troubled by feelings of rage. But I don’t want to be presumptuous—there are other reasons to read an essay that promises to tell you what to do with your anger. Maybe you think I have an agenda. Perhaps you have formed an idea of what my rage is about, and you disagree with that figment, and you are hate-reading these words right now, waiting for me to reveal the source of my own rage so that you can write a nasty comment at the end of this post or troll me on social media or try to cancel me or dox me or incite violence against me or come to my house and sneak onto my porch and stare balefully into my front windows or throw an egg at my car or trample deliberately on the ox-eye sunflowers that are bursting around my mailbox or put a bomb in my mailbox or disagree with me strenuously in your heart. There is a wide range of potential negative responses, and I don’t have time to list them all. The point here is that one must contend with them, and that is another reason to feel rage.