by David Greer

And I shall have some peace there, for peace comes dropping slow,

Dropping from the veils of the morning to where the cricket sings;

There midnight’s all a glimmer, and noon a purple glow,

And evening full of the linnet’s wings.

—Excerpt from The Lake Isle of Innisfree, by William Butler Yeats

Our people lived as part of everything. We were so much a part of nature, we were just like the birds, the animals, the fish. We were like the mountains. Our people lived that way. We knew there was an intelligence, a strength, a power, far beyond ourselves…. Everybody had the right to comfort, to security, the right to food, a home, the use of the land. This is because we believed that everything was put here by a great and wonderful intelligence.

—Excerpt from Saltwater People, by Dave Elliott

Visitors to my cabin in a forest glade on a small island in the Salish Sea almost always remark upon the silence. It’s true, if you’re freshly arrived from an urban community, the silence at first seems absolute and a little overwhelming. It’s only when you quiet yourself that the silence surrounding you starts to come alive with the texture and colour of natural sounds.

Some sounds may seem easily identifiable to visitors if only because their creators are visible. The slow thunk-thunk-thunk of a raven’s wings beating the air as it passes arrow-straight across the circle of blue sky over the glade. The chittering of a bald eagle high in a fir. The cat-like mew of a red-eyed spotted towhee rooting through underbrush. Other noises require more careful observation and familiarity but are instantly identifiable to those who know them. The faint scrape of the jaws of a yellowjacket backing down a cedar post, a grey ball of nest paper slowly enlarging beneath its mandibles. The lazy kre-e-e-eck? deep in a cedar, like a creaking rusty door in a haunted house: the territorial call of a male Pacific tree frog, gold and green and shadow-secluded. The urgent whistling of a juvenile barred owl, harassing its parent for freshly killed flesh. And in the gloaming, not the soft sound of the linnet’s wings, but those of its close cousin the house finch in this part of the world six thousand miles from Yeats country.

Other sounds once heard in the glade are now long gone, such as the distant drumming of the blue grouse, a reliable sign of spring until they were extirpated by feral cats that had been abandoned by their humans and in due course occupied a vacant ecological niche for predators of eggs laid on the ground. Not surprisingly, killdeer are on the decline here as well. Humans releasing cats they can’t care for into the wild are unlikely to imagine the cumulative results of what they may perceive as an act of kindness (rescuing unwanted kittens from drowning), but the world turns on unintended consequences, and the fact that blue grouse drumming is now but a fond memory is merely one example. The less one feels connected to the natural world, the greater the likelihood and frequency of unintended consequences wreaking multiplying havoc, whether caused by cats or CO2.

The sound that captures my attention this June moment is the ethereal spiralling call of a Swainson’s thrush, one of the many little brown birds that elude identification unless you know them well or open your Merlin Bird ID app and point your phone in the general direction of birdsong, in which case an accurate description magically and without hesitation pops up on your screen. I knew it was a thrush of some description and so pointed my phone towards its general vicinity. Merlin obligingly identified it as Swainson’s, adding it to the growing list on my screen of others noted by Merlin in the preceding minutes: spotted towhee, Pacific-slope flycatcher, chestnut-backed chickadee, brown-headed cowbird, common raven, Wilson’s warbler.

The Victorians had something of an obsession with collecting and cataloging small flying creatures and naming them after a member of a gentleman’s club before pinning their corpses under glass onto a felt backing for cabinet (and later museum) display. Times change, and changing twenty-first century sensibilities have resulted in the proposed relabelling of numbers of birds named after men deemed to be of questionable character. In the U.S., for example, McCown’s longspur, named in honor of a Confederate general, is now more descriptively known as the thick-billed longspur.

Alexander Wilson (the warbler’s namesake) and William John Swainson by all accounts were mild-mannered ornithologists with beliefs unremarkable for the times in which they lived (early nineteenth century). To date there has been no renaming of the birds named after Wilson and Swainson, but that seems likely to change, thanks to a grassroots campaign to replace every common eponymous bird name with a descriptive name, on the basis that the system of naming birds after people is an outdated vestige of colonialism in ornithological history and that it discourages inclusivity among the birder community. Our beliefs are shaped by the times in which we live, and beliefs considered harmless or even progressive in today’s society may be the subject of condemnation at some future time. Be that as it may, there is little tolerance today for past beliefs out of step with evolving modern-day ethics. The upshot is that Wilson and Swainson and Cooper (hawk) and Brandt (cormorant) and Anna (hummingbird) and their ilk appear destined to be relegated to the dustbin of ornithological history sooner rather than later.

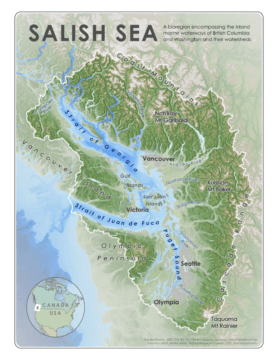

Newcomers to this island called South Pender invariably find peace here, and that’s a large part of its attraction. But long ago, before British authorities gave the island its present name in the nineteenth century to honor a Royal Navy surveyor, and long before eighteenth Spanish expeditions into the Salish Sea, South Pender Island was known by a different name—SDȺY¸ES, in the SENĆOŦEN language of the W̱SÁNEĆ People, whose traditional territory extended over much of the Salish Sea. The inland sea that encompasses the inland marine waterways and watersheds of what is now southern British Columbia and northern Washington state is a bioregion so ecologically rich that it historically supported a wide diversity of indigenous peoples. The peace that they had enjoyed on the waters and beaches of the Salish Sea since time immemorial was abruptly and forever shattered the moment Europeans judged the region suitable for colonization and began quarreling with one another as to whether it should fall under the distant rule of Britain or Spain.

But long before that happened, and long before Swainson’s time, the W̱SÁNEĆ People paid close attention to the little brown thrush with the swirling flutelike song. In their SENĆOŦEN language, they called it W̱EW̱ELEŚ,and it held significance to them far beyond its natural beauty. Their interest lay less in documentation of species than in recording relationships among species—a natural bias for people who not only depended on local creatures and plants for their daily sustenance but also saw themselves as one with rather being above and apart from nature.

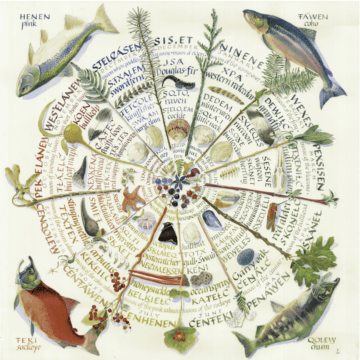

The W̱SÁNEĆ People’s understanding of these relationships was recorded in a calendar with far more daily relevance to them than the Gregorian calendar had to Europeans. Their 13 Moon Calendar described typical weather and abundant foods during each of the 13 moons of the year, with a particular emphasis on signs to watch for in the relationships among plants and animals during each moon. The first moon of spring was the Frog Moon, WEXES, named after the tree frog pictured above. Today, the noisy February concerts held by hundreds of amorous tree frogs gathered together for the purpose of making whoopee are considered by many locals to be the first real sign of spring; in the 13 Moon Calendar, the concert held more valuable significance as the sign that the tide was about to bring in the annual herring bounty from the sea.

In recent years, the 13 Moon Calendar, originally an oral creation, has been the subject of several pictorial representations. In the one pictured in this piece, the Sockeye Moon of late spring shows Swainson’s thrush paired with the ripening of the salmonberry (ELILE in the SENĆOŦEN language), a raspberry-like fruit native to the Pacific coast of North America. W̱SÁNEĆ elders tell how Swainson’s thrush is known as the salmonberry bird because its songs color the berries in various shades. Ethnobotanists Nancy Turner and Richard Hebda recorded the story, as told to them by elders Violet Williams and Elsie Claxton, in their book Saanich Ethnobotany: Culturally Important Plants of the W̱SÁNEĆ People (Royal BC Museum, 2012):

“Swainson’s Thrush invited Raven to her house for a meal. She told her kids to take their baskets out to pick berries. She started singing her song. In her song, she nicknames each of four colours of salmonberries and then sings their common names:

NENELKXELIK the little black/dark red-headed ones

NENELPKIK the little white-headed ones

NENELKEMEK the little red-headed ones

NENELPWIK the little blond/golden-headed ones

WEWELEWELEWELEWESI ripen, ripen, ripen, ripen

As she sang, her children’s baskets filled up.

Afterwards, Raven said, ‘You come to my house.’ Swainson’s thrush did. Raven told his children to go out with their baskets. They did that for their dad. Raven sang and sang in his croaking voice, but the baskets never got full.”

The ripening of salmonberries is not the only significant event under the Sockeye Moon. Under that moon, sockeye salmon are closely paired with ocean spray flowers, which come into full bloom when the sockeye pass through the Salish Sea on their migration from the open Pacific to the rivers in which they spawn. On the same day I first heard the Swainson’s thrush, I also ate salmonberries on my way to the outhouse. That was pure coincidence, but the thrushes I heard were within yards of the berries, even though I didn’t actually spot the notoriously shy birds. Meanwhile, along the road to my cabin, the aptly named ocean spray flowers hung over the road like high surf cresting before breaking onto sand. Everything was late this year due to the influence of La Niña, but the harvest still unfolded in the precise sequence foretold by the 13 Moon Calendar.

The Victorians had little economic need of the species they so diligently cataloged, and identifying them was more significant than understanding their behavior. For the W̱SÁNEĆ People, labelling creatures was secondary to understanding their place in the island ecosystem. Economic thinking is often rooted in spiritual belief, which in turn may be shaped to support economic thinking. In a Christian society that views the Holy Bible as the foundation of community values, Genesis 1:26 is indisputable: “And God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth.” When you view yourself not as lord and master over creation but rather as on an equal footing with all those critters on which you directly depend to keep you in good fettle, it does tend to color your attitudes. The Thirteen Moon Calendar concerns itself with cooperation and understanding rather than conquest and education. Darwin, of course, was an outlier: the observer who challenged prevailing attitudes about creation and fundamentally altered human understanding of relationships and interdependencies among species, and most particularly island species, which evolve in radically different ways than species across continents.

Darwin still has his critics, most notably among Evangelical Christians. But times change in unexpected ways. Half a century ago, few might have predicted that virtually every public speech today (speaking at least of Canada) would begin with an introduction acknowledging the presence of the speaker and audience on traditional indigenous territory. More than a century and a half ago, the W̱SÁNEĆ People of islands such as SDȺY¸ES (South Pender) were removed from their traditional homeland to small “reserves”, primarily on what became known as the Saanich (an Anglicization of W̱SÁNEĆ) Peninsula. Their place was taken by white settlers, mostly emigrants from post-Victorian England. Banishment to the reserves, which W̱SÁNEĆ People were forbidden to leave without a special pass from the government Indian agent, separated the W̱SÁNEĆ People from the rich natural bounty on which they depended, destroying their economy and traditional means of survival in one fell swoop. Complaints about injustice were met with silence and contempt. Out of sight, out of mind was the approach favoured by the British and later Canadian authorities, and if that didn’t work, “assimilation” into the colonial culture through forced removal of indigenous children from their families to residential schools where they were forbidden to speak their language might be worth a try.

Canadians growing up in the 1960s and 1970s, demonstrating against wars and for women’s rights, for the most part remained blissfully unaware of the harm done by residential schools if they were even aware of their existence. People’s concerns are shaped by the times in which they live, and the question of indigenous rights simply did not exist on the radar of the average Canadian or American. Indigenous leaders, however, had for decades with persistence and dignity been quietly pressing their case through the courts when faced with the deaf ear of government. Finally, beginning in the 1980s, court decisions very gradually began to recognize the injustices done to native peoples in Canada and to pay heed to the right of aboriginal title to land. It was an infinitesimally slow process requiring endlessly repeated efforts by indigenous peoples to obtain government commitments to enforce court decisions. Over decades the pendulum has slowly begun to move from colonialist indifference to indigenous claims to a slowly expanding recognition of traditional indigenous rights and acknowledgment of past harms visited on indigenous communities by colonial governments. In more recent years, all levels of government in Canada have adopted policies of reconciliation with indigenous peoples, especially after discoveries at locations of closed residential schools across the nation of unmarked graves of young students forcibly removed from their communities, with fatal consequences.

In recent years, in the spirit of reconciliation, W̱SÁNEĆ elders have engaged with residents of North and South Pender islands in events that have included instruction on the identification and use of wild plants, salmon bakes under the Sockeye Moon, and a workshop teaching the meanings and pronunciation of words in the SENĆOŦEN language. As Dave Elliott explains in Saltwater People, the language of the W̱SÁNEĆ People comes from the land and is embedded in the land. Words are not merely sterile signifiers denoting identities of objects; rather, they are sacred sounds with magical significance. One small example of the complexity of the SENĆOŦEN language is the variety of words depicting the different meanings of each of the Swainson’s thrush’s different notes when it colors the salmonberries. In the worldview of the W̱SÁNEĆ People, the sound of spoken language is simply another aspect of oneness with nature.

Time is a wheel. Sometimes it crushes, sometimes it carries us forward, but it also sometimes moves in a circular motion in ways we can’t foresee. After centuries of being crushed under the wheel of colonialism, indigenous peoples in Canada and in some other countries are gradually reclaiming the heritage that was taken from them. Much work remains to be done in societies with colonial pasts, and understanding and respect are a necessary starting point.