by Ethan Seavey

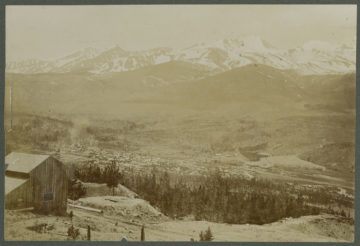

Breckenridge, Colorado: a village in the Rocky Mountains which is now known for its popular ski resort. Before 1859, it was a valley with a lush Blue River running through the crease by the foothills of the Ten Mile Range. In 1859, gold was first mined in Breckenridge. After 1859, over 5,000 white men (some estimate closer to 8,000) flocked to the valley, and the village sprung up quickly after.

Many of those men (for they were nearly all men) had stopped on their way home from the gold rush on the west coast, and others had come from out east. They had experience in mining, which not only meant knowledge of how to effectively collect the gold from the mountains, but that they knew how to survive in the isolated wilderness. In the 1860s, a gold miner from Breckenridge would earn about three dollars a day. Let’s make this clear: three dollars a day was a good amount of money. Many people across America were only earning a dollar, and others had no job. If being a miner didn’t pay well, no one would have come so far to work such a dangerous job. Every day, he would spend one dollar on his boarding, another on food and booze and an hour in a brothel, and send the third home to his family out east.

Mining meant stability at home (usually, back East) when work was hard to find. Still, they weren’t educated enough to learn that they were being cheated. The owner of the claim would take an average of ten dollars of gold from each of his men, every day. The owners lived in nice homes, and some of them never even laid their eyes on the mines. If you could afford it, you wouldn’t be living in Breckenridge.

There was no law. The owners with the most money had the most guns; they could take on the most employees, and pay them less in exchange for protection and stability; and when their gold ran out, they could then take over their neighbor’s profitable claim by force. There were no ethics, no religions, excluding the divine GOLD.

These folks were mainly from Pennsylvania; these folks from Pennsylvania mainly descended from Nordic, Celtic, and Germanic people; these folks knew only basic log cabin construction and limited geologic and geographical knowledge; these folks were rough and lawless; these folks shot each other daily on Main Street; these folks had their eardrums blown out by dynamite explosions; these folks handled mercury and arsenic in their bare hands; these folks saw mines collapse and trains crash. These folks never got rich, but these folks earned enough to live, unlike many. These folks died at 38.

Today at the historic Valley Brook Cemetery in town, there are many headstones of single men, whose bodies were never sent back East, who didn’t have family. Some were buried by their fraternal organizations. Those men lived short lives but successful ones. Other bodies have been re-buried several times to their final, nameless resting place. The only way you can tell someone is buried is because they weren’t buried in coffins, and the dirt would sink as their bodies decayed.

And now I am here. Marz: one of my ancestral names is on an old headstone.

Think of the world as it is: land and peoples, gathered in groups not defined by clear borders like the ones we scribble on maps. Three hundred years ago, my ancestors were a muddy mix of Nordic and Celtic and Germanic peoples. They came to America in search of better homes and better food. Some wound up in Pennsylvania. Some of their children, unable to find better homes and better food near their parents, fled west.

They did not belong here. Other people belonged here. The Ute people knew the Blue River Valley intimately. They had been coming every summer to hunt antelope and bison for thousands of years. In the winters they would head back down into the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, nearby Denver now. Before leaving in the summer, they would strategically light wildfires to promote the growth of plants such as lodgepole pines whose pinecones spread more seeds when exposed to heat. They did not farm here. They did not need to farm. They would hunt bison for just enough meat to feed themselves. They cut down just as many trees as they needed. They lived in harmony with the land, used it to last. They foresaw thousands of years of more harmony in the beautiful Rocky Mountains.

When these white folks, the colonizers, crossed the continental divide, their first action was to cut down hundreds of lodgepole pines and build a fort. It was named Fort Mary B., and it was built out of fear of the Ute. They never encountered any violence in the Blue River Valley, excluding the violence that they caused to themselves. These men, in turn, would be among those who killed the Mountain Ute people en masse and forced them off their land.

By 1887 all Native people would be forced to live on reservations, far from their ancestral lands. They would be forced into the southwest corner of Colorado; they would be forced to learn how to farm on arid, harsh ground; they would be forced to relinquish their horses; they would be forced to send their children to American boarding schools, where nearly half of them died due to infectious illnesses.

Very few Ute people survive today, on these same reservations.

Unlike the Ute, these colonizers didn’t know how to live on this land. They hunted the bison to local extinction. They introduced plants which would choke out the native ones. They cut down acres of lodgepole pines to build cabins and mine the gold underneath, not caring about sowing the seeds for more timber tomorrow.

They planned to get in, get the gold as quickly as possible, and get out. Breckenridge was not supposed to be the miner’s permanent home. They didn’t care about the land they destroyed in their search, so they used several different types of mining, all of which devastated the landscape.

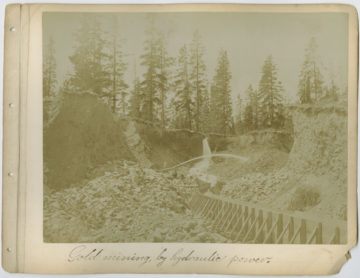

J. Frank Willis Photograph Album. Breckenridge History, Colorado.

This summer, I’m working at Lomax Placer Gulch as a historical interpreter. We give tours of the mine at the site and then do gold panning in the stream. The aforementioned gulch is not a natural one. It was created using hydraulic equipment. It was technology they’d already used in California, so the miners were very adept at it. To collect the gold buried deep, they’d wash the side of the mountain by directing an iron nozzle which pushed out water with incredible force. That mud would wash down into sluice boxes, and they could then collect the gold that collects at the bottom. That dirt, which made up several stories of that mountain, was washed down into the valley, and it will never come back. This “gulch” is a scar on the Earth.

Now, hydraulic mining wasn’t the only type of gold mining in Breckenridge. Mineshafts litter the mountains still, though most have been caved in to keep people out. The ruins of dredges sit in ponds, and a replica of one is now a burger joint. The product of these mining boats: dead rivers filled with rocks, uninhabitable valleys.

For nearly a hundred years, the white men carved up the fertile lands for useless yellow rock. After gold mining was shut down during World War II, it seemed that they might finally leave. The population dropped sharply. These folks did not know how to live on this land without support from the foothills.

Then, more recently immigrated Nordic folks came over. They recognized the mountains for their skiing potential. This was 1961, and Europeans and American hippies flocked to the town for cheap skiing and totally free housing, as long as they were okay with squatting in an abandoned miner’s cabin.

To make the ski hills, they continue to make the land inaccessible to life. They cut down trees for proper paths. They put up chair lifts over their habitats. They still have not learned how to live in harmony; they have just found a new, sustainable way to mine the mountains.

(Note to reader: The so-called “Ute” people call themselves “Núuchi-u” but the colonizers preferred the word the Spaniards made up to describe all Indigenous American peoples: “Yuta.” I learned this fact very late into my research. It stands as a good reminder that I am learning from the side of the colonizers. I am descended from colonizers. They lived selfishly and stole everything from the people living here, including the right to their own name. I am an active colonizer. We white Europeans have lived on this land for almost two hundred years, and the Nùuchi-u have lived on this land for thousands. I want to emphasize the importance of learning their name, but I will leave this piece unedited out of transparency.)

(Note to self: I am always learning and changing the truth as I do.)

Source: Breckenridge History public resources