by Pranab Bardhan

All of the articles in this series can be found here.

After LSE I have seen Jean Drèze mostly in India, usually in conferences in Delhi and Kolkata, and at Amartya Sen’s home in Santiniketan (where he used to stay whenever the two of them were writing books together). The Kolkata conferences were the annual ones that Amartya-da used to organize for some years, held usually at the Taj Bengal five-star hotel, which Jean would refuse to stay in. While others would take the 2-hour flight from Delhi to Kolkata, Jean would take the 24-hour train in the crowded second-class compartment. Then he’d call me and often stay with me in my Kolkata apartment. If Kalpana was around and it was winter she’d warm the bath water for him and arrange a comfortable raised bed for him; but Jean would refuse even those minor luxuries, and insist on taking cold showers and sleeping on the floor.

After LSE I have seen Jean Drèze mostly in India, usually in conferences in Delhi and Kolkata, and at Amartya Sen’s home in Santiniketan (where he used to stay whenever the two of them were writing books together). The Kolkata conferences were the annual ones that Amartya-da used to organize for some years, held usually at the Taj Bengal five-star hotel, which Jean would refuse to stay in. While others would take the 2-hour flight from Delhi to Kolkata, Jean would take the 24-hour train in the crowded second-class compartment. Then he’d call me and often stay with me in my Kolkata apartment. If Kalpana was around and it was winter she’d warm the bath water for him and arrange a comfortable raised bed for him; but Jean would refuse even those minor luxuries, and insist on taking cold showers and sleeping on the floor.

During his days at the Delhi School of Economics faculty he’d stay in a nearby jhuggi or slum (with his newly-married activist wife, Bela Bhatia). Soon he became an Indian citizen and started devoting more of his time to social activism and less on teaching. He left Delhi and was first in Allahabad, and now for some years in Ranchi. But much of the time he’d be on the road, walking, biking, and occasionally in crowded trains and buses. Once I remember getting a long email from him describing his walking trip (padayatra) to one of the poorest villages in Kalahandi, Odisha. He had heard of near-starvation conditions there. As he was walking he saw a man carrying a headload of vegetables, going to the marketplace several miles away. He started walking along and talking to him (probably in Hindi, which Jean speaks much better than I do) and found out that the man had not eaten anything for the previous day or so, and was hoping to eat after he sold his vegetables in the market. At one point Jean offered to carry the head load at least part of the way to the market. The man emphatically refused, but Jean kept on nagging. After some time the man yielded, but when Jean tried to take the load on his head, it felt so heavy, Jean wrote to me, that he almost fell on the ground—just to think that this wiry little man was carrying it for miles with no food over the previous day! Read more »

A little while ago my friend Bethany requested that I write an essay on the following topic: “Can/should pedantry be reconstituted as a virtue, maybe particularly for women.” I filed it away on my list of possible future essay ideas, but like a

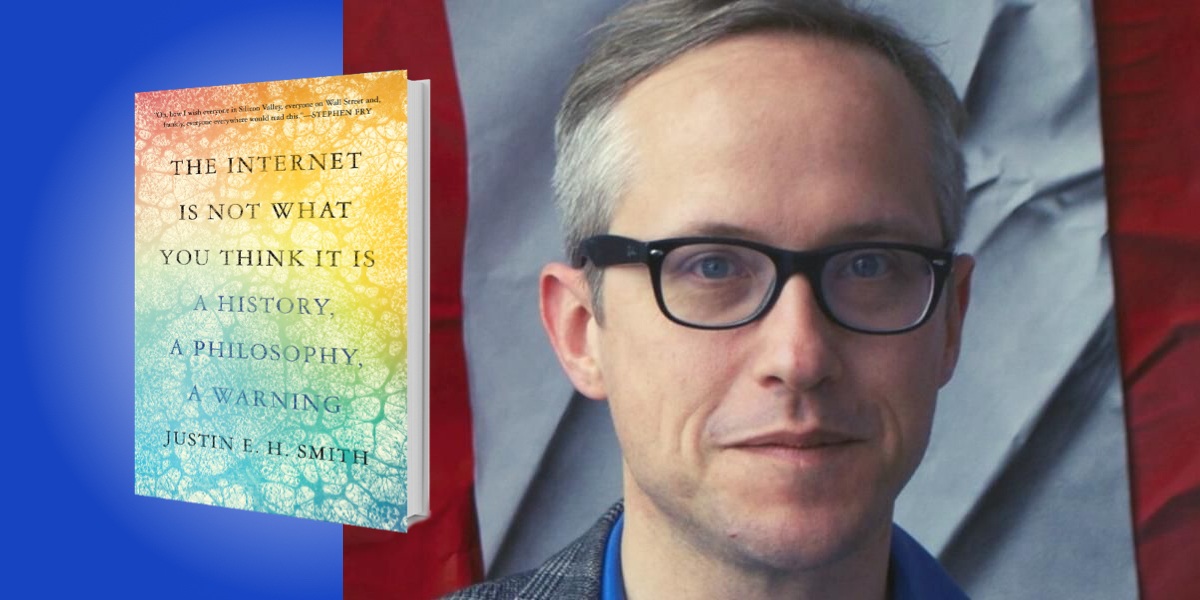

A little while ago my friend Bethany requested that I write an essay on the following topic: “Can/should pedantry be reconstituted as a virtue, maybe particularly for women.” I filed it away on my list of possible future essay ideas, but like a  Justin E. H. Smith’s recent book,

Justin E. H. Smith’s recent book,  I’m not sure what Americans were like in the 18th and 19th century, but they have to have been a lot tougher, less whining, less self-important and paradoxically more exceptional without thinking they were exceptional than Americans of today.

I’m not sure what Americans were like in the 18th and 19th century, but they have to have been a lot tougher, less whining, less self-important and paradoxically more exceptional without thinking they were exceptional than Americans of today.

Sughra Raza. Untitled, ca 2008.

Sughra Raza. Untitled, ca 2008.

This past spring, I found myself sitting, masked, at a wooden desk among a scattering of scientific researchers at the Museo Galileo in Florence. Next to me was a thick reference book on the history of astronomical instruments and a smaller work on the sundials and other measuring devices built into the churches of Florence to mark the cyclical turning points of cosmic time. The gnomon of Santa Maria del Fiore, for instance, consisted of a bronzina, a small hole set into the lantern ninety meters above that acted as a camera oscura and projected an image of the sun onto the cathedral floor far below. At noon on the day of the solstice, the solar disc superimposed itself perfectly onto a round marble slab, not quite a yard in diameter, situated along the inlaid meridian. I studied the explanations of astronomical quadrants and astrolabes and the armilla equinoziale, the armillary sphere of Santa Maria Novella, made up of two conjoined iron rings mounted on the façade that told the time of day and year based on the position of their elliptical shadow, when all at once it occurred to me that I’d wanted to write about something else altogether, about a person I occasionally encountered, a phantom living somewhere inside me: the young woman who’d decided not to leave, not to move to Berlin after all, to rip up the letter of acceptance to the art academy she received all those years ago and to stay put, in New York. Alive somewhere, in some other iteration of being, was a parallel existence in an alternative universe, one of the infinite spheres of possibility in which I’d decided differently and become a different woman.

This past spring, I found myself sitting, masked, at a wooden desk among a scattering of scientific researchers at the Museo Galileo in Florence. Next to me was a thick reference book on the history of astronomical instruments and a smaller work on the sundials and other measuring devices built into the churches of Florence to mark the cyclical turning points of cosmic time. The gnomon of Santa Maria del Fiore, for instance, consisted of a bronzina, a small hole set into the lantern ninety meters above that acted as a camera oscura and projected an image of the sun onto the cathedral floor far below. At noon on the day of the solstice, the solar disc superimposed itself perfectly onto a round marble slab, not quite a yard in diameter, situated along the inlaid meridian. I studied the explanations of astronomical quadrants and astrolabes and the armilla equinoziale, the armillary sphere of Santa Maria Novella, made up of two conjoined iron rings mounted on the façade that told the time of day and year based on the position of their elliptical shadow, when all at once it occurred to me that I’d wanted to write about something else altogether, about a person I occasionally encountered, a phantom living somewhere inside me: the young woman who’d decided not to leave, not to move to Berlin after all, to rip up the letter of acceptance to the art academy she received all those years ago and to stay put, in New York. Alive somewhere, in some other iteration of being, was a parallel existence in an alternative universe, one of the infinite spheres of possibility in which I’d decided differently and become a different woman. Although by no means the only ones, two models of human beings and their relation to society are prominent in modern social and political thought. At first glance they seem incompatible, but I want to sketch them out and start to establish how they might plausibly be made to fit together.

Although by no means the only ones, two models of human beings and their relation to society are prominent in modern social and political thought. At first glance they seem incompatible, but I want to sketch them out and start to establish how they might plausibly be made to fit together.

Anneliese Hager. Untitled. ca. 1940-1950

Anneliese Hager. Untitled. ca. 1940-1950