by Jonathan Kujawa

In May of 2020 we lost John Conway [0]. We discussed some of his mathematical accomplishments here at 3QD. He was a true original.

At the time, I deliberately avoided discussing Conway’s most famous work: the Game of Life. Like a 60s rock band, Conway had mixed feelings about his most famous hit. But like hits that stand the test of time, it deserves its reputation. The Game of Life still has surprises and mysteries for us nearly sixty years after its invention. I thought it’d be worth talking about some of the latest discoveries.

Conway invented the rules of Life in the late sixties. According to Wikipedia, Conway was simultaneously motivated by Stanislaw Ulam’s work on the growth of crystals and by parallel investigations by John von Neumann on self-replicating systems. For the former, I highly recommend the Crystalverse website for instructions on growing your own crystals. For the latter, think of robots who can build more copies of themself like these Xenobots.

Ulam and von Neumann worked at the Los Alamos National Lab in the 1940s and 50s. They could only dream of Xenobots. Instead, as a simplified model, both assumed that they were working in two dimensions, and both space and time could be chopped up into discrete, irreducible parts. They were interested in what sorts of dynamical, self-organizing processes could happen in such a world. Read more »

Kon Trubkovich. The Antepenultimate End, 2019.

Kon Trubkovich. The Antepenultimate End, 2019. It seems we’re always tinkering with those eternities, not just to cherish their value or find their meaning, but to transform them into something else. Maybe that’s what creative writing ultimately is—momentary eternities arranged so that they somehow move the reader the way a perfect arrangement of musical notes might do. Reading is a compelling pastime for millions because words function as artfully selected indicators of events and images that readers will complete in their own minds, as they follow verbal guideposts for the imagination to begin to do its work.

It seems we’re always tinkering with those eternities, not just to cherish their value or find their meaning, but to transform them into something else. Maybe that’s what creative writing ultimately is—momentary eternities arranged so that they somehow move the reader the way a perfect arrangement of musical notes might do. Reading is a compelling pastime for millions because words function as artfully selected indicators of events and images that readers will complete in their own minds, as they follow verbal guideposts for the imagination to begin to do its work.

My last night in the house on Euclid Avenue will go one of two ways:

My last night in the house on Euclid Avenue will go one of two ways: Jean-François Millet, a Frenchman, frowned beneath his full beard as he lay dying in Barbizon. It was 1875, and he was not to be confused with Claude Monet—not yet—who would later paint water lilies and haystacks but wasn’t, in 1875, rich and famous; on the contrary—and in spite of Édouard Manet’s having just painted him painting from the vantage of a covered paddle boat, appearing pretty well-to-do in the process—he was barely getting by.

Jean-François Millet, a Frenchman, frowned beneath his full beard as he lay dying in Barbizon. It was 1875, and he was not to be confused with Claude Monet—not yet—who would later paint water lilies and haystacks but wasn’t, in 1875, rich and famous; on the contrary—and in spite of Édouard Manet’s having just painted him painting from the vantage of a covered paddle boat, appearing pretty well-to-do in the process—he was barely getting by.

As with game theory, I also attended some courses in Berkeley in another relatively new subject for me, Psychology and Economics (later called Behavioral Economics). In particular I liked the course jointly taught by George Akerlof and Daniel Kahneman (then at Berkeley Psychology Department, later at Princeton). I remember during that time I was once talking to George when my friend and colleague the econometrician Tom Rothenberg came over and asked me to describe in one sentence what I had learned so far from the Akerlof-Kahneman course. I said, somewhat flippantly: “Kahneman is telling us that people are dumber than we economists think, and George is telling us that people are nicer than we economists think”. George liked this description so much that in the next class he started the lecture with my remark. On the dumbness of people I later read somewhere that Kahneman’s earlier fellow-Israeli co-author Amos Tversky once said when asked what he was working on, “My colleagues, they study artificial intelligence; me, I study natural stupidity.”

As with game theory, I also attended some courses in Berkeley in another relatively new subject for me, Psychology and Economics (later called Behavioral Economics). In particular I liked the course jointly taught by George Akerlof and Daniel Kahneman (then at Berkeley Psychology Department, later at Princeton). I remember during that time I was once talking to George when my friend and colleague the econometrician Tom Rothenberg came over and asked me to describe in one sentence what I had learned so far from the Akerlof-Kahneman course. I said, somewhat flippantly: “Kahneman is telling us that people are dumber than we economists think, and George is telling us that people are nicer than we economists think”. George liked this description so much that in the next class he started the lecture with my remark. On the dumbness of people I later read somewhere that Kahneman’s earlier fellow-Israeli co-author Amos Tversky once said when asked what he was working on, “My colleagues, they study artificial intelligence; me, I study natural stupidity.”![Righting America at the Creation Museum (Medicine, Science, and Religion in Historical Context) by [Susan L. Trollinger, William Vance Trollinger]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/511yK1hsSBL.jpg)

Herschel Walker claims that we have enough trees already, that we send China our clean air and they return their dirty air to us, that evolution makes no sense since there are still apes around, and freely offers other astute scientific insights. He may be among the least knowledgeable (to put it mildly) candidates running for office, but he’s not alone and many candidates, I suspect, are also surprisingly innocent of basic math and science. Since innumeracy and science illiteracy remain significant drivers of bad policy decisions, it’s not unreasonable to suggest that congressional candidates (house and senate) be obliged to get a passing grade on a simple quiz.

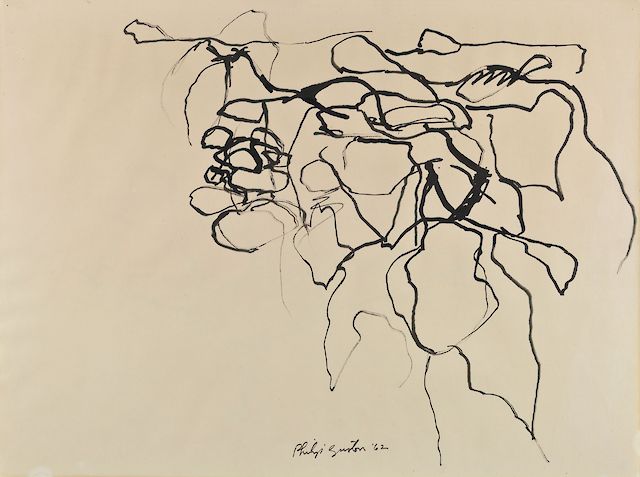

Herschel Walker claims that we have enough trees already, that we send China our clean air and they return their dirty air to us, that evolution makes no sense since there are still apes around, and freely offers other astute scientific insights. He may be among the least knowledgeable (to put it mildly) candidates running for office, but he’s not alone and many candidates, I suspect, are also surprisingly innocent of basic math and science. Since innumeracy and science illiteracy remain significant drivers of bad policy decisions, it’s not unreasonable to suggest that congressional candidates (house and senate) be obliged to get a passing grade on a simple quiz. Philip Guston. Still Life, 1962.

Philip Guston. Still Life, 1962.

I recently listened to a discussion on the topic of

I recently listened to a discussion on the topic of  This summer I noticed that I was sharing a lot of sunset photos on social media. I don’t think of myself as a photographer, and I’m much more likely to share words than images. When I thought about it, I realized this wasn’t a sudden change. I’ve been taking the odd set of sunset pictures with my Canon every now and then, and I’ve noticed that my eyes are increasingly drawn to the sky and the light when I look at landscape photos.

This summer I noticed that I was sharing a lot of sunset photos on social media. I don’t think of myself as a photographer, and I’m much more likely to share words than images. When I thought about it, I realized this wasn’t a sudden change. I’ve been taking the odd set of sunset pictures with my Canon every now and then, and I’ve noticed that my eyes are increasingly drawn to the sky and the light when I look at landscape photos.