by Ashutosh Jogalekar

Freeman Dyson combined a luminous intelligence with a genuine sensitivity toward human problems that was unprecedented among his generation’s scientists. In his contributions to mathematics and theoretical physics he was second to none in the 20th century, but in the range of his thinking and writing he was probably unique. He made seminal contributions to science, advised the U.S government on critical national security issues and won almost every award for his contributions that a scientist could. His understanding of human problems found expression in elegant prose dispersed in an autobiography and in essays and book reviews in the New Yorker and other sources. Along with being a great scientist he was also a cherished friend and family man who raised six children. He was one of a kind. Those of us who could call him a friend, colleague or mentor were blessed.

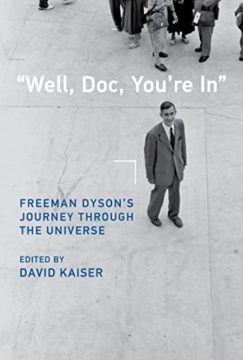

Now there is a volume commemorating his remarkable mind from MIT Press that is a must-read for anyone who wants to appreciate the sheer diversity of ideas he generated and lives he touched. From spaceships powered by exploding nuclear bombs to the eponymous “Dyson spheres” that could be used by advanced alien civilizations to capture energy from their suns, from his seminal work in quantum electrodynamics to his unique theories for the origins of life, from advising the United States government to writing far-ranging books for the public that were in equal parts science and poetry, Dyson’s roving mind roamed across the physical and human universe. All these aspects of his life and career are described by a group of well-known scientists and science writers, including his son, George and daughter, Esther. Edited by the eminent physicist and historian of science David Kaiser, the volume brings it all together. I myself was privileged to write a chapter about Dyson’s little-known but fascinating foray into the origins of life. Read more »

Now there is a volume commemorating his remarkable mind from MIT Press that is a must-read for anyone who wants to appreciate the sheer diversity of ideas he generated and lives he touched. From spaceships powered by exploding nuclear bombs to the eponymous “Dyson spheres” that could be used by advanced alien civilizations to capture energy from their suns, from his seminal work in quantum electrodynamics to his unique theories for the origins of life, from advising the United States government to writing far-ranging books for the public that were in equal parts science and poetry, Dyson’s roving mind roamed across the physical and human universe. All these aspects of his life and career are described by a group of well-known scientists and science writers, including his son, George and daughter, Esther. Edited by the eminent physicist and historian of science David Kaiser, the volume brings it all together. I myself was privileged to write a chapter about Dyson’s little-known but fascinating foray into the origins of life. Read more »

“Mankind was first taught to stammer the proposition of equality” – “Everyone is equal to everyone else” – “In a religious context, and only later was it made into morality,” Nietzsche wrote. Elsewhere, he called “human equality,” or “moral equality,” a specifically “Christian concept, no less crazy [than the soul],” moral equality “has passed even more deeply into the tissue of modernity…[it] furnishes the prototype of all theories of equal rights.”

“Mankind was first taught to stammer the proposition of equality” – “Everyone is equal to everyone else” – “In a religious context, and only later was it made into morality,” Nietzsche wrote. Elsewhere, he called “human equality,” or “moral equality,” a specifically “Christian concept, no less crazy [than the soul],” moral equality “has passed even more deeply into the tissue of modernity…[it] furnishes the prototype of all theories of equal rights.”

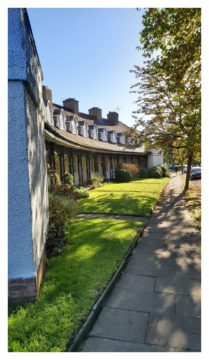

Port Sunlight was a model village constricted in the Wirral, in the Liverpool area, by the Lever brothers, and especially under the inspiration of William Lever, later lord Leverhulme. Their fortune was based on the manufacture of soap, and the village was built next to the factory in the Victorian/Edwardian era, for the employees and their families. It’s certainly a remarkable place, with different houses designed by various architects, parks, allotments, everything an Edwardian working class person might want. An enlightened employer, Lever was still a paternalist: he claimed his village was a an exercise in profit sharing, because “It would not do you much good if you send it down your throats in the form of bottles of whisky, bags of sweets, or fat geese at Christmas. On the other hand, if you leave the money with me, I shall use it to provide for you everything that makes life pleasant – nice houses, comfortable homes, and healthy recreation.” Overseers had the right to visit any house at any time to check for ‘cleanliness’ and that the rules about who could live in which house were observed (men and women could only share accommodation if they were in the same family). Still, by the stands of the day it was quite progressive – schools, art gallery, recreation of all sorts for the employees were important.

Port Sunlight was a model village constricted in the Wirral, in the Liverpool area, by the Lever brothers, and especially under the inspiration of William Lever, later lord Leverhulme. Their fortune was based on the manufacture of soap, and the village was built next to the factory in the Victorian/Edwardian era, for the employees and their families. It’s certainly a remarkable place, with different houses designed by various architects, parks, allotments, everything an Edwardian working class person might want. An enlightened employer, Lever was still a paternalist: he claimed his village was a an exercise in profit sharing, because “It would not do you much good if you send it down your throats in the form of bottles of whisky, bags of sweets, or fat geese at Christmas. On the other hand, if you leave the money with me, I shall use it to provide for you everything that makes life pleasant – nice houses, comfortable homes, and healthy recreation.” Overseers had the right to visit any house at any time to check for ‘cleanliness’ and that the rules about who could live in which house were observed (men and women could only share accommodation if they were in the same family). Still, by the stands of the day it was quite progressive – schools, art gallery, recreation of all sorts for the employees were important.

In 1930, the German anthropologist Berthold Laufer published a monograph on the phenomenon of people eating dirt.

In 1930, the German anthropologist Berthold Laufer published a monograph on the phenomenon of people eating dirt. My grandmother’s bird of choice is the rooster. She was raised in rural Kentucky and now lives in rural Wisconsin. She collects all sorts of roosters (and, by extension, some hens): wall art, printed dish towels, ceramic statues as small as a pinky and as large as a lamp, coin bowls and blankets and something nostalgic in each one.

My grandmother’s bird of choice is the rooster. She was raised in rural Kentucky and now lives in rural Wisconsin. She collects all sorts of roosters (and, by extension, some hens): wall art, printed dish towels, ceramic statues as small as a pinky and as large as a lamp, coin bowls and blankets and something nostalgic in each one.

Sughra Raza. Shadow Self-Portrait in a Reflection of a Window in a Window.

Sughra Raza. Shadow Self-Portrait in a Reflection of a Window in a Window.  A couple of years ago I briefly became famous for hating Vancouver. By “famous” I mean that a hundred thousand people or so read

A couple of years ago I briefly became famous for hating Vancouver. By “famous” I mean that a hundred thousand people or so read

It was announced last week that scientists have integrated neurons from human brains into infant rat brains, resulting in new insights about how our brain cells grow and connect, and some hope of a deeper understanding of neural disorders.

It was announced last week that scientists have integrated neurons from human brains into infant rat brains, resulting in new insights about how our brain cells grow and connect, and some hope of a deeper understanding of neural disorders.  Visualize a purple dog, the exercise said. Imagine it in great detail; picture it approaching you in a friendly way. So I did. I thought of a spaniel: long silky ears, beautiful coat, all a nice lilac color. Pale purple whiskers. The dog was friendly but not effusive. I’m not a dog person, but I wouldn’t have minded meeting this dog. All right, now what? The exercise went on to say something along the lines of “Wonderful! If you can visualize that purple dog, can’t you imagine your own life as being full of amazing possibilities?”

Visualize a purple dog, the exercise said. Imagine it in great detail; picture it approaching you in a friendly way. So I did. I thought of a spaniel: long silky ears, beautiful coat, all a nice lilac color. Pale purple whiskers. The dog was friendly but not effusive. I’m not a dog person, but I wouldn’t have minded meeting this dog. All right, now what? The exercise went on to say something along the lines of “Wonderful! If you can visualize that purple dog, can’t you imagine your own life as being full of amazing possibilities?”