Window in Franzensfeste, South Tyrol.

Fear of Flying

by Deanna Kreisel (Doctor Waffle Blog)

It’s not about dying, really—it’s about knowing you’re about to die. Not in the abstract way that we haphazardly confront our own mortality as we reach middle age and contemplate getting old. And not even in the way (I imagine) that someone with a terminal diagnosis might think about death—sooner than expected and no longer theoretical. It’s much more immediate than that.

It’s not about dying, really—it’s about knowing you’re about to die. Not in the abstract way that we haphazardly confront our own mortality as we reach middle age and contemplate getting old. And not even in the way (I imagine) that someone with a terminal diagnosis might think about death—sooner than expected and no longer theoretical. It’s much more immediate than that.

Whenever I teach logical reasoning to my students, I start with a classic syllogism to illustrate deduction: All humans are mortal; Socrates is a human; therefore Socrates is mortal. For an example of inductive reasoning I ask them to think about the major premise of the syllogism: All humans are mortal. How do we know this statement is true? The only reason we assume that anyone currently alive is mortal (including ourselves) is that a very large number of people have died before us. We have no proof.

But if you’re in an airplane hurtling toward the earth, my guess is that such airy sophistries fly right up to the ceiling along with the beverage carts. Suddenly an incurable cancer diagnosis might seem kind of warm and cozy in comparison: you would have some time to get more used to the idea, say your goodbyes, rewrite your will to indulge your current spites. People in a crashing airplane might just have time to clutch an arm or an armrest, gabble a hasty prayer, perhaps make a quick phone call to leave an unerasable message on a loved one’s voicemail.

And that’s what I’m really afraid of: those 60-to-600 seconds. Read more »

The Mysterious Origin of Corn

by Carol A Westbrook

The new research technician walked into my lab at the University of Chicago, and I introduced her to my research group.

“I enjoyed the walk from home to the lab,” she added. “Everyone in Hyde Park is so friendly! Why just today I stopped to talk to a gardener. He proceeded to tell me about the corn plants he was cultivating. He showed me how he pollinates the plants by hand, and he began to discuss the complicated genetics of corn. “Honestly, Hyde Park is a very impressive place to live. Even the gardeners are highly educated!”

Everyone laughed. “Looks like you came across George Beadle,” someone said. “He’s a Nobel laureate and former president of the University. He’s now retired and doing the research that he always wanted—to determine the origin of the corn plant using genetics.” He likes nothing more than to discuss his theories with anyone who walks by, and spends his day working in his beloved corn fields, where he is doing his research on corn plants.”

This is a true story. George Beadle won the Nobel prize in 1958 for his genetic work on the mold Neurospora, which led to the “one gene-one enzyme” theory, a true breakthrough in understanding the function of DNA. But Nobel prize or no Nobel prize, Beadle’s real passion was the work he started while a graduate student at Cornell University, and that is to solve the mystery of corn’s origin. Read more »

Monday, November 14, 2022

The Gendered Ape, Essay 8: Every Mammal Owns A Clitoris!

Editor’s Note: Frans de Waal’s new book, Different: Gender Through the Eyes of a Primatologist, has generated some controversy and misunderstanding. He will address these issues in a series of short essays which will be published at 3QD and can all be seen in one place here. More comments on these essays can also be seen at Frans de Waal’s Facebook page.

by Frans de Waal

Sigmund Freud — a man with little anatomical expertise and no vagina – invented the vaginal orgasm. Considering it superior to the clitoral orgasm, he dismissed the latter as something for children. Women who enjoyed it were stuck at an infantile stage, ripe for psychiatric treatment.

It was Freud’s way of saying that female orgasm without male penetration doesn’t count.

Anatomists, however, have been unable to find the nerve endings in the muscular vaginal wall required for pleasure, while the clitoris has an abundance. Even though the clitoris is a marvel of engineering, there was a time when evolutionary biologists dismissed it as a by-product that wasn’t any more functional than the male nipple. Stephen Jay Gould declared the clitoris a “glorious accident.”

The medical community, too, still acts as if this little organ hardly matters even though the clitoris has a higher density of sensory points and nerve endings than the penis. Read more »

Beware, Proceed with Caution

by Martin Butler

Going with the evidence is one of the defining principles of the modern mind. Science leads the way on this, but the principle has been applied more generally. Thus, enlightened public policy should be based on research and statistics rather than emotion, prejudice or blind tradition. After all, it’s only rational to base our decisions on the observable evidence, whether in our individual lives or more generally. And yet I would argue that evidence, ironically, indicates that in some respects at least we are far too wedded to this principle.

How is it that the dawning of the age of reason, which saw science and technology become preeminent in western culture, coincided with the industrial revolution, which is turning out to be disastrous for the natural world and, quite possibly, humanity too? Our rationalism seems to have created something which is, in retrospect at least, deeply irrational.

When the industrial revolution was moving through the gears from the end of the 18th century and throughout the 19thcentury there was little clear evidence of the environmental disasters awaiting us. Of course many voices revolted against the tide but these voices were almost exclusively based on emotion and romanticism rather than hard scientific evidence. Why shouldn’t we do something if there is no evidence of harm? And offending our sensibilities does not constitute harm. The colossal productive power unleashed by the industrial revolution promised many benefits, and the dark satanic mills were just the price we had to pay for wealth and progress. No matter how ugly the change might appear at first, breaking with the past was surely just the inevitable tide of history. Looking back, however, it seems the romantics, the traditionalists and even the Luddites had a point.

So, where and why did it all go wrong? Science only finds something if it is looking for it, and it never just looks for evidence. It frames research questions in a particular way and uses particular methods to investigate. All this rests on assumptions which are not themselves questioned. Read more »

Monday Poem

Narragansett Evening Walk to Base Library

Two young men greeted a new crew member on a ship’s quarterdeck 60 years ago and, in a matter of weeks, by simple challenge, introduced this then 18 year-old who’d never really read a book through to the lives that can be found in them. —Thank you Anthony Gaeta and Edmund Budde for your life-altering input.

bay to my right (my rite of road and sea:

I hold to its shoulder, I sail, I walk the line)

the bay moved as I moved, but in retrograde

as if the way I moved had something to do

with the way the black bay moved, how it tracked,

how it perfectly matched my pace, but

slipping behind, opposed, relative

(Albert would have a formula or two

to spin about this if he were here)

behind too, over shoulder, my steel grey ship at pier,

transfigured in cloud of cool white light,

a spray from lamps on tall poles ashore

and aboard from lamps on mast and yards

among needles of antennae which gleamed

above its raked stack in electric cloud enmeshed

in photon aura, its edges feathered into night,

enveloped as it lay upon the shimmering skin of bay

from here, she’s as still as the thought from which she came:

upheld steel on water arrayed in light, heavy as weight,

sheer as a bubble, line of pier behind etched clean,

keen as a horizon knife

library ahead, behind

a ship at night

the bay to my right (as I said) slid dark

at the confluence of all nights,

the lights of low barracks and high offices

of the base ahead all aimed west, skipped off bay

each of its trillion tribulations jittering at lightspeed

fractured by bay’s breeze-moiled black surface

in splintered sight

ahead the books I aimed to read,

books I’d come to love since Tony & Ed

in the generosity of their own fresh enlightenment

had teamed to bring new tools to this greenhorn’s

stymied brain to spring its self-locked latch

to let some fresh air in crisp as this breeze

blowing ‘cross the bay from where to everywhere,

troubling Narragansett from then

to me here now

Jim Culleny

12/16/19

Hyperintelligence: Art, AI, and the Limits of Cognition

by Jochen Szangolies

On May 11, 1997, chess computer Deep Blue dealt then-world chess champion Garry Kasparov a decisive defeat, marking the first time a computer system was able to defeat the top human chess player in a tournament setting. Shortly afterwards, AI chess superiority firmly established, humanity abandoned the game of chess as having now become pointless. Nowadays, with chess engines on regular home PCs easily outsmarting the best humans to ever play the game, chess has become relegated to a mere historical curiosity and obscure benchmark for computational supremacy over feeble human minds.

Except, of course, that’s not what happened. Human interest in chess has not appreciably waned, despite having had to cede the top spot to silicon-based number-crunchers (and the alleged introduction of novel backdoors to cheating). This echoes a pattern well visible throughout the history of technological development: faster modes of transportation—by car, or even on horseback—have not eliminated human competitive racing; great cranes effortlessly raising tonnes of weight does not keep us from competitively lifting mere hundreds of kilos; the invention of photography has not kept humans from drawing realistic likenesses.

Why, then, worry about AI art? What we value, it seems, is not performance as such, but specifically human performance. We are interested in humans racing or playing each other, even in the face of superior non-human agencies. Should we not expect the same pattern to continue: AI creates art equal to or exceeding that of its human progenitors, to nobody’s great interest? Read more »

For Good

by Michael Abraham

I wake early—not with the dawn but not long after it—and I stare out the window at a little conglomeration of Brooklyn backyards, severed from one another by brick walls and dotted with deciduous trees holding out their last against autumn. I am all wrapped up with the man I am dating, here in his home, in his bed, in Clinton Hill. He jokes with me, makes fun of me for being up so early, since I am one for sleeping late and one who protests mightily should sleeping late prove not to be an option. But not this morning. This morning, something momentous is about to happen, something about which I have thought many times, thought of as a far distant possibility, one that might never reach me. Indeed, I have written before about how it would never happen, how it could not happen. In these many flights of fancy about it happening, I have pondered deeply what it would feel like, decided it would feel none too good, that it would be a tragedy. But, here I am, poised on the precipice in the gray of a November morning just past seven a.m., poised on the precipice of it happening, and I have no sense of how it is that I feel, of whether it is a tragedy or a triumph or simply one of many things that must happen in the winding course of a life. I am leaving New York. I cannot say if it is for good that I am leaving, meaning both that I cannot say if it is a good thing and that I cannot say if it is forever. I ache as I wonder what it means to leave for good, as I wonder if that’s what I’m doing. Read more »

Perceptions

Empty Brains and the Fringes of Psychology

by Rebecca Baumgartner

There’s a fascinating figure wandering aimlessly around the halls of psychology on the internet, and his name is Robert Epstein.

Epstein is a 69-year-old psychologist who trained in B.F. Skinner’s pigeon lab in the 70s and now works at the American Institute for Behavioral Research and Technology in California, a nonprofit supporting a theory of the brain that supposedly “does not rely on metaphor.” Despite his credentials – he holds a doctorate from Harvard – both his nonprofit’s website and his own professional website give you the unsettling feeling that he exists on the fringes of psychology, and science more generally. This feeling is confirmed when you read anything he’s written.

One of the most vilified pieces of writing I’ve ever read was his piece “The Empty Brain,” which first appeared in Aeon back in 2016, but didn’t cross my desk until recently. In a nutshell, the article is about Epstein’s claim that the brain does not process information or contain memories – he believes these concepts are merely metaphors borrowed from computing and do not accurately describe what the brain does.

What brains do, in Epstein’s view, is change in an orderly way in response to input and allow us to relive an experience we’ve had before – nothing so mechanistic as “processing” and “storing” things! (It’s never made clear how this new formulation differs from processing information and storing memories.)

He also fails to realize that under that formulation, you could just as easily say that computers don’t store anything; the hard drive has simply been changed in an orderly way in response to input. Apparently our computers are not computers either. Read more »

We Can’t Work (It) Out

by Ada Bronowski

A philosopher and a stand-up comedian walk into a bar…the beginning of a joke? Or perhaps a history of humanity from the margins. The philosopher and the stand-up comedian are two figures that keep reappearing across the ages, cutting familiar silhouettes of odd bodies making odd claims about the world and its inhabitants.

A philosopher and a stand-up comedian walk into a bar…the beginning of a joke? Or perhaps a history of humanity from the margins. The philosopher and the stand-up comedian are two figures that keep reappearing across the ages, cutting familiar silhouettes of odd bodies making odd claims about the world and its inhabitants.

The first stand-up comedian of Western civilisation is a demure character who makes a brief appearance in book 2 of Homer’s Iliad. Thersites is ‘the ugliest man to come to Troy’, with bow-legs, sagging shoulders, a hollow chest and an egg-shaped head. He is the sort ‘who would do anything to get a laugh’. He is the Jon Stewart of the Trojan War, telling the blood- (and gold-) thirsty leaders of that insanely annihilating campaign, just that. In front of the whole assembled army, Thersites lays bare the hypocrisy of the king of kings, Agamemnon, who talks of honour, glory, and justice, but in fact does nothing but steal, hoard, rape and exploit. Thersites is immediately punished for his effrontery, beaten up by Odysseus and reduced to a miserable tear-drenched heap, the laughingstock of the army. What began in laughter ends in laughter, but the audience has switched sides.

This is a brief but famous scene. Thersites has done the rounds in the history of ideas from hero of the little people as heralded by the first modern political theorist Hugo Grotius, and as a symbol of the revolutionary spirit by Karl Marx, to makeshift populist from the Greek historian Thucydides to Nietzsche via Shakespeare who vilifies Thersites in Troilus and Cressida. In the play, Thersites’ very presence vitiates the possibility of disinterested virtues: love, justice and honour turn, under his relentlessly berating tongue, into cover-words for rotten self-interest. Read more »

Catspeak

by Brooks Riley

The Green Dragon?

by Mike O’Brien

China has been on my mind lately. It has also been on the mind of my federal government and political press. Recent revelations that China interfered with our elections in 2019, and possibly in 2021, have caused a bit of a kerfuffle, tinged by panic, indignation, and the kind of reflexive Trudeau-blaming that has become a sad fixture of Canadian public discourse. I miss the days when we blamed everything on Americans; it was unifying and accurate.

Frankly, I would be surprised and a little disappointed if China weren’t meddling in our elections. It would be a sign of indifference, a dashing of this country’s deepest collective hope that important countries notice us and even mention our name from time to time. It’s not like our elections are un-meddled-in anyhow, given that we share the world’s longest unprotected border with one of the 20th century’s most egregious election-meddlers. I’m not saying that official agents of the United States government are targeting our political processes. They don’t have to. The fact that most of our media is American, or pale copies thereof, does a better job of ideological and doctrinal contamination than any State Department stooge could hope to accomplish. The idea that Canadian society could ever be safe from outside predation is a dangerous folly. I suppose the Canadian political and security establishment knows this very well, and the feigned shock at any particular incursion is mostly performed to effect a diplomatic message.

I am glad that Trudeau is in power, rather than the ghoulish Republican-aping Conservatives. I used to give him a hard time for his tap-dancing around the incompatibility of Canada’s economic and environmental goals. I still do, but I used to, too (R.I.P. Mitch Hedberg). But I doubt Trudeau, or anyone, could win another election on the promise of taking steps sufficiently drastic to bring our economy in line with our public environmental commitments, let alone with actual environmental necessity. Too many voters are committed to preserving an unsustainable way of life, and that commitment is generously encouraged by a commercial media landscape awash in energy-industry propaganda. Read more »

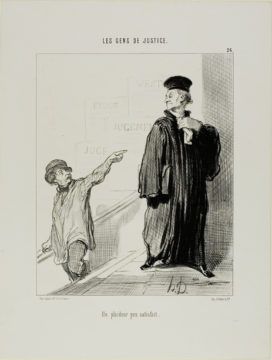

Against Consistency Critiques

by Joseph Shieber

Suppose you had a friend whom you knew to be a lover of good coffee. You ask him how he likes his coffee machine and he replies that it’s okay. He emphasizes that one of the best features of the coffee machine is that it’s extremely reliable; each cup of coffee is the same as the last.

Curious, you ask your friend to brew a cup for you. After taking a sip, you exclaim, “Ugh, this tastes awful.”

“Yes,” your friend replies, “but at least it’s consistent.”

You’d likely think that such a response was crazy! Presumably, if given a choice between a machine that consistently produces bad cups of coffee and a machine that is inconsistent, but that at least occasionally produces good cups of coffee, anyone would choose the inconsistent machine. At least it gives you the CHANCE of getting a good cup of coffee!

Despite the seeming sensibleness of this view, it is surprisingly hard to keep its lesson in mind – for me no less than for others.

I was mindful of this as I read Liza Batkin’s essay, “The Kingdom of Antonin Scalia,” in The New Yorker.

Batkin’s work is only the latest in a long line of think-pieces charging that the Supreme Court’s now-ascendent conservatives aren’t true to their own espoused doctrines, but only apply those doctrines consistently when they yield their preferred political outcomes (examples of this style of piece go back, in my recollection, at least as far as Bush v Gore). Read more »

Monday Photo

The Sublime Child in the Persona of Moses

by Shadab Zeest Hashmi

First, because Moses, or the prophet Musa as we know him in the Quran, is an unusual hero— a newborn all on his own, swaddled and floating in a papyrus basket on the Nile— my brothers and I couldn’t get enough of his story as children. Second, it is also a story of siblings: his sister keeps an eye on him, walking along the river as the baby drifts in the reeds farther and farther away from home, his brother, the prophet Harun accompanies him through many crucial journeys later in life, another reason the story was relatable. Returning to the narration as a young woman, a mother, I found myself more interested in the heroines in the story: Musa’s birth-mother whose maternal instinct and faith are tested in a time of persecution, the Pharaoh’s wife Asiya who adopts the foundling as her own, confronting her megalomaniac husband’s ire and successfully raising a child of slaves and the prophesied contender to the pharaoh’s power under his own roof. As a diaspora writer, especially one wielding the colonizer’s tongue and negotiating the contradictory gifts of language, I have yet again been drawn to Musa. He is an outsider and an insider— one who carries a “knot on his tongue”— the burden of interpreting and speaking, not entirely out of choice, to radically different entities: God, the Pharaoh and his own people. Among the myriad facets of the legend, the most enduring is the innocence at the heart of his mythos, the exoteric quality of wisdom explored beautifully in mystic writings and poetry as a complementary aspect of the esoteric.

First, because Moses, or the prophet Musa as we know him in the Quran, is an unusual hero— a newborn all on his own, swaddled and floating in a papyrus basket on the Nile— my brothers and I couldn’t get enough of his story as children. Second, it is also a story of siblings: his sister keeps an eye on him, walking along the river as the baby drifts in the reeds farther and farther away from home, his brother, the prophet Harun accompanies him through many crucial journeys later in life, another reason the story was relatable. Returning to the narration as a young woman, a mother, I found myself more interested in the heroines in the story: Musa’s birth-mother whose maternal instinct and faith are tested in a time of persecution, the Pharaoh’s wife Asiya who adopts the foundling as her own, confronting her megalomaniac husband’s ire and successfully raising a child of slaves and the prophesied contender to the pharaoh’s power under his own roof. As a diaspora writer, especially one wielding the colonizer’s tongue and negotiating the contradictory gifts of language, I have yet again been drawn to Musa. He is an outsider and an insider— one who carries a “knot on his tongue”— the burden of interpreting and speaking, not entirely out of choice, to radically different entities: God, the Pharaoh and his own people. Among the myriad facets of the legend, the most enduring is the innocence at the heart of his mythos, the exoteric quality of wisdom explored beautifully in mystic writings and poetry as a complementary aspect of the esoteric.

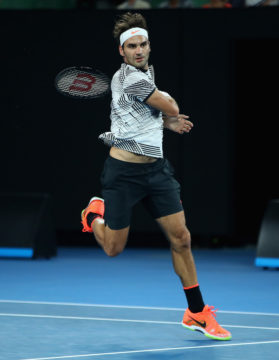

The End of an Era: On Roger Federer’s Retirement

by Derek Neal

The one regret of my life so far is never having seen Roger Federer play tennis in person. As Federer announced his retirement this year, I’ll never have the chance. The closest I came was the summer of 2017: I was in Italy and planned on flying to Stuttgart to see Federer play in a grass court tournament as preparation for Wimbledon. A few weeks before I was set to leave, I applied for a job at an English language school, largely at the behest of my girlfriend, who was unhappy with the fact that I was “studying” Italian in the mornings and flâning the streets in the afternoons, all while she spent long days toiling away as an unpaid intern in a law office, a common situation in Italy. I didn’t expect to get the job—I had little experience and no real credentials—but I would soon learn that neither of these things mattered, superseded as they were by my being a native speaker. I got the job and had to cancel my trip.

The one regret of my life so far is never having seen Roger Federer play tennis in person. As Federer announced his retirement this year, I’ll never have the chance. The closest I came was the summer of 2017: I was in Italy and planned on flying to Stuttgart to see Federer play in a grass court tournament as preparation for Wimbledon. A few weeks before I was set to leave, I applied for a job at an English language school, largely at the behest of my girlfriend, who was unhappy with the fact that I was “studying” Italian in the mornings and flâning the streets in the afternoons, all while she spent long days toiling away as an unpaid intern in a law office, a common situation in Italy. I didn’t expect to get the job—I had little experience and no real credentials—but I would soon learn that neither of these things mattered, superseded as they were by my being a native speaker. I got the job and had to cancel my trip.

For readers who are not fans of Federer, my above statement may seem hyperbolic, but I am writing in earnest. Sports, and specifically tennis, being an individual sport, have the ability to become representative of something larger than themselves. In tennis, the great players embody a way of life through their playing styles. Federer, being the most graceful and beautiful player, makes us think that one can live a life in this way, moving through the world in harmony with our surroundings, never forcing one’s desires but letting their fulfillment come to us, and acting in accordance with what might be called the laws of nature. This is how Federer moves around the tennis court. At his best, he seems to be a Zen sage who has attained enlightenment. Rafael Nadal is the foil to Federer’s grace. Nadal shows us that anything can be achieved through hard work and perseverance. He plays with force and power, grunting as he hits the ball, bending the world to his will and conquering all that lays before him. Fans of Nadal, I imagine, have this worldview and admire him for its representation in his style of play. Read more »

On the Road: Chile Can’t Decide

by Bill Murray

Charles Darwin was just shy of 24 years old, his eyes open in wonder as the HMS Beagle slid along the shore of the largest island in the archipelago of Tierra del Fuego. His eyes grew wider as bonfires flared along the water’s edge. “They must have lighted the fires immediately upon observing the vessel, but whether for the purpose of communicating the news or attracting our attention, we do not know,” he wrote.

These shore people called themselves Ona and Yaghan. Canoeists and fishermen adept at navigating the labyrinth of channels in these straits, in wintertime they kept fires constantly stoked for warmth. The Yaghan wore only the scantest clothing despite the cold. To fend off wind and the rain, they smeared seal fat over their bodies.

The Ona lived across the strait, on an island just visible through the spray and mist. History calls them fierce warriors who adorned themselves with necklaces of bone, shell and tendon, and who, wearing heavy furs and leather shoes, intimidated the bare-skinned Yaghan. Darwin gave them their backhanded due, calling them “wretched lords of this wretched land.” An acerbic settler once described life hereabouts as 65 unpleasant days per year complimented by 300 days of rain and storms. Read more »

Monday, November 7, 2022

The Puzzle of Working Class Politics Around the World

by Pranab Bardhan

The recent spectacular rise of extreme right-wing parties in Italy and Sweden and the squeaking narrow victory of Lula in Brazil have revived the puzzle that in the face of economic crisis and rising inequality the working classes are often turning politically right, instead of left. This is as prevalent in developing countries as in the rich countries of North America and Europe. One difference between the two sets of countries may be that while in rich countries this trend is markedly among less-educated, older, and more rural workers, in some developing countries, say India, this is also the case for more educated, aspirational, urban youth. The other difference between the two sets of countries is that working classes in developing countries are now in general more pro-globalization than in developed countries—more pro-globalization in Vietnam, Bangladesh, Nigeria and India, than say in France or US, as surveys of attitudes to globalization show.

But in both sets of countries large numbers of workers (and peasants), defying the usual pre-suppositions about inequality, have rallied under right-wing leaders who are often plutocrats, like Erdoğan, Orbán, Trump, Le Pen, or Nigel Farage (the original Brexit leader). In India the poor supporters of Modi do not care much that he is cozy with some of the richest Indian billionaire businessmen in the world. Workers are worried more about the rise in insecurity in their own lives, and do not seem to care much about the rising wealth of the top 1 percent. And this insecurity is not just about economic insecurity in terms of their jobs and incomes but also cultural insecurity of one kind or another, as I have illustrated in my recent book A World of Insecurity: Democratic Disenchantment in Rich and Poor Countries (Harvard University Press and Harper Collins India, 2022).

There is, however, an important difference between the US and other countries on right-wing attitude to economic insecurity. Read more »

Rule of Law

by Terese Svoboda

“My account omitted many very serious incidents,” writes Bertrand Roehner, the French historiographer whose analysis on statistics about violence in post-war Japan I used in my Graywolf Nonfiction Prize memoir, Black Glasses Like Clark Kent. He began emailing me at this September about a six-volume, two thousand page report concerning Japanese casualties during the Occupation that has just been released in Japanese after sixty years of suppression.[i] Black Glasses Like Clark Kent is a memoir about my uncle, an MP in postwar Japan, that told of GIs executing GIs in an American-held Tokyo prison. Among many other things, the book takes a close look at censorship in postwar Japan.

“My account omitted many very serious incidents,” writes Bertrand Roehner, the French historiographer whose analysis on statistics about violence in post-war Japan I used in my Graywolf Nonfiction Prize memoir, Black Glasses Like Clark Kent. He began emailing me at this September about a six-volume, two thousand page report concerning Japanese casualties during the Occupation that has just been released in Japanese after sixty years of suppression.[i] Black Glasses Like Clark Kent is a memoir about my uncle, an MP in postwar Japan, that told of GIs executing GIs in an American-held Tokyo prison. Among many other things, the book takes a close look at censorship in postwar Japan.

A fog of censorship comes up during war about casualties. In the obfuscating haze after bombs explode – O Say Can You See? – bodies get thrown into too many pieces to count, bodies are attributed to those who don’t count, bodies simply aren’t counted. Authorities have their reasons to undercount. The mighty conqueror vanquishes the conquered by a mere flick of its thumb; the conquered want to seem relatively unscathed. If nothing else, undercounting encourages enlistment in future wars. Finding out just how many soldiers die in a war is extremely difficult. Counting the dead during an occupation with its even hazier rules is almost impossible. MacArthur made it even more difficult due to his overwhelming policy of censorship. “Even the Allied military reports were subject to self-censorship,” writes Roehner. In Black Glasses I was just trying to find out how many American soldiers convicted of capital transgressions had been officially executed by Americans. After four years of research, I did not discover that number. Counting civilians in either case is another thing entirely. According to the Geneva Convention, civilians are not supposed to be killed at all, although these days civilians are more and more the actual targets of conflict. (See Ukraine). Read more »

Carlos Donjuan. Together Alone.

Carlos Donjuan. Together Alone.