by Jeroen Bouterse

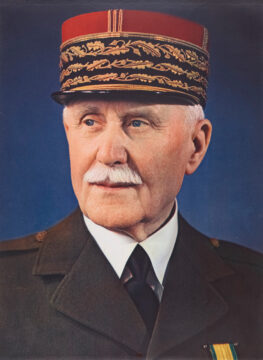

In Timur Vermes’ best-selling novel Er ist wieder da (‘He’s back’), Adolf Hitler wakes up in Berlin. Somewhat disoriented after discovering the year is 2011, he soon finds his way to the public eye again: he is understandably regarded as a skilled Hitler impersonator, an excellent ironic act for a 21st-century comedy show. His handlers don’t mind the fact that he never breaks character.

In Timur Vermes’ best-selling novel Er ist wieder da (‘He’s back’), Adolf Hitler wakes up in Berlin. Somewhat disoriented after discovering the year is 2011, he soon finds his way to the public eye again: he is understandably regarded as a skilled Hitler impersonator, an excellent ironic act for a 21st-century comedy show. His handlers don’t mind the fact that he never breaks character.

Clips make it to YouTube, and the ‘Führer’ becomes a beloved persona. After humiliating the ineffectual leader of a far-right fringe party, he is assaulted by skinheads. Politicians express their sympathies, a book deal follows. The novel ends with its main character at the head of an up-and-coming party, whose slogan is: Es war nicht alles schlecht – “it wasn’t all bad”.

Vermes puts Hitler in a Germany that believes it is finally able to laugh at him, or at itself through him. Commercial media encourage his popularity, which at first seems tongue-in-cheek but gradually turns out to be more than that. The country is unprepared for his literal-minded and violent racist madness – and for the traction it subtly gathers, the threads in our own discourse that it starts to pull on again. Everyone thinks they know Hitler, but fails to recognize him when he is among us now.

I thought of this story again as I read historian Alec Ryrie’s new book The Age of Hitler and How We Will Survive It. Ryrie’s thesis is that after the Second World War, the Atlantic and European world placed Hitler at the center of the Western value system (as its negative mirror image). This went at the cost of another historical figure, whose return we have similarly stopped expecting: in the nineteenth and early twentieth century, Jesus had represented a moral authority that was deeply felt not just by Christians, but also by free-thinkers and atheists. In the mid-twentieth century, Nazism became the new moral absolute. This model lasted for decades, but Ryrie discerns a new cultural shift, one that is happening now. With the age of Atlantic hegemony, the ‘age of Hitler’ is coming to an end too. What lies beyond it is still up for grabs. Read more »

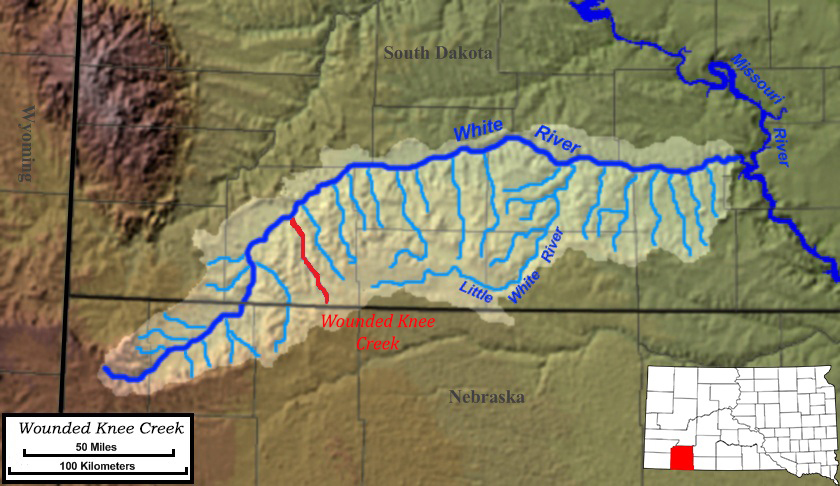

The Lakota name for Wounded Knee Creek is Čaŋkpe Opi Wakpala. The first letter is a -ch sound. The ŋ signifies not an n, but nasalization as when you say unh-unh to mean no.

The Lakota name for Wounded Knee Creek is Čaŋkpe Opi Wakpala. The first letter is a -ch sound. The ŋ signifies not an n, but nasalization as when you say unh-unh to mean no.

1. Roses

1. Roses

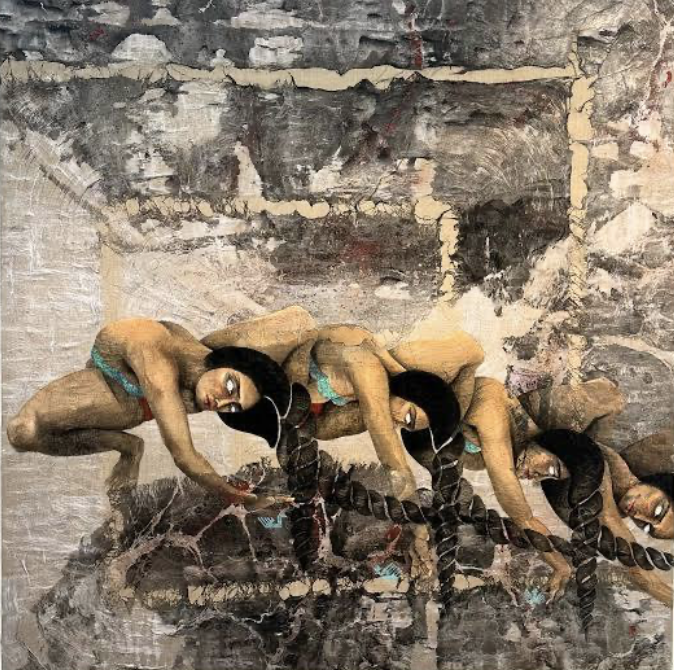

Hayv Kahraman. Rain Birds Ritual, 2025.

Hayv Kahraman. Rain Birds Ritual, 2025. Morgan Meis and I have been talking about art for years. We’re friends and interlocutors, so I’ll refer to him by first name here for the sake of transparency. Morgan writes about painting; I write about movies. We spent the pandemic exchanging letters with each other about films by Terrence Malick, Lars von Trier, and Krzysztof Kieślowski. These letters were later collected in a mad book called

Morgan Meis and I have been talking about art for years. We’re friends and interlocutors, so I’ll refer to him by first name here for the sake of transparency. Morgan writes about painting; I write about movies. We spent the pandemic exchanging letters with each other about films by Terrence Malick, Lars von Trier, and Krzysztof Kieślowski. These letters were later collected in a mad book called

The other day, in a cavernous sports superstore, I thought of J.G. Ballard. Echoey. Compartmentalised. Fluorescent. Stuffed with product. It was, probably quite obviously, the sort of place Ballard might have imagined the norms of society suddenly collapsing in on themselves, unable to carry their own contradictions.

The other day, in a cavernous sports superstore, I thought of J.G. Ballard. Echoey. Compartmentalised. Fluorescent. Stuffed with product. It was, probably quite obviously, the sort of place Ballard might have imagined the norms of society suddenly collapsing in on themselves, unable to carry their own contradictions.