by Mark Harvey

Opinion has caused more trouble on this little earth than plagues or earthquakes. —Voltaire (1694 – 1778)

About the only good thing that comes out of huge natural disasters is that it brings otherwise feuding and even warring countries together in humanitarian rescue efforts. Immediately after the recent earthquake in Turkey and Syria, rescue teams from all over the world amassed huge amounts of food, medicine, clothing, and rescue equipment, boarded airplanes and trucks and swarmed into the two heavily damaged countries to do some genuine, unadulterated good.

An 80-member world-class search and rescue team plus four search dogs with world-class noses from the UK hit the ground in Gaziantep, Turkey, barely two days after the quake. The team arrived with specialized seismic listening devices, concrete cutting equipment, and shoring materials. The crew is self-sufficient and brought its own food, water, shelter, communication, and sanitation gear.

An 80-member rescue team from China, also with four dogs, arrived in Turkey the same day as the UK team. The Chinese came with 20 tons of medical and communications equipment. Read more »

About a third of the way through a first-year humanities honors course, one of my more engaged and talkative students pulled me aside after class for a private chat. She waited, clearly anxious, while the rest of her classmates filed out and then turned to me with her eyes already filling up with tears.

About a third of the way through a first-year humanities honors course, one of my more engaged and talkative students pulled me aside after class for a private chat. She waited, clearly anxious, while the rest of her classmates filed out and then turned to me with her eyes already filling up with tears.

My father, the son of Italian immigrants, was a member of the working class. There were things within reach, and things that were not in reach, and he accepted this. He never pushed his children to broaden their horizons, and would have been satisfied to see them in traditional working-class vocations. When I came home from school eager to show off my grades, he poked fun at me. The prospect of pursuing an intellectual career was alien to him; in his view, taking out student loans to go to college or university was a way for banks to trap the “little guy.” When I presented him with the papers, he refused to sign. There was no discussion. I eventually moved out and managed to get my BFA anyway, and when I wound up as a finalist for a Fulbright, the doctor who performed the general checkup required by the awarding commission—I was still covered by my father’s Blue Cross plan, but only because I was still technically a dependent and it didn’t cost him anything—took him aside and told him that a Fulbright would be “quite a feather in your daughter’s cap.”

My father, the son of Italian immigrants, was a member of the working class. There were things within reach, and things that were not in reach, and he accepted this. He never pushed his children to broaden their horizons, and would have been satisfied to see them in traditional working-class vocations. When I came home from school eager to show off my grades, he poked fun at me. The prospect of pursuing an intellectual career was alien to him; in his view, taking out student loans to go to college or university was a way for banks to trap the “little guy.” When I presented him with the papers, he refused to sign. There was no discussion. I eventually moved out and managed to get my BFA anyway, and when I wound up as a finalist for a Fulbright, the doctor who performed the general checkup required by the awarding commission—I was still covered by my father’s Blue Cross plan, but only because I was still technically a dependent and it didn’t cost him anything—took him aside and told him that a Fulbright would be “quite a feather in your daughter’s cap.”

Sughra Raza. Just a Street Corner. Boston, 2022.

Sughra Raza. Just a Street Corner. Boston, 2022.

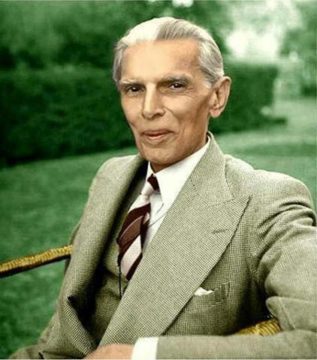

Mohammed Ali Jinnah’s Last Visit to Kashmir 10 May – 25 July 1944

Mohammed Ali Jinnah’s Last Visit to Kashmir 10 May – 25 July 1944

No metaphor for cancer does it justice. As a medical oncologist and cancer researcher, I struggle constantly with how people perceive cancer. Until a person suffers from it or sees a loved one suffer from the devastation of this disease, cancer remains an abstract term or concept. But it is an abstract concept that kills 10 million people around the world every year. Ten million people every year. How do we get people to understand that this is a lethal disease that deserves attention. That deserves more funding. That deserves more minds thinking about how to stop the continual suffering that metastatic cancer causes.

No metaphor for cancer does it justice. As a medical oncologist and cancer researcher, I struggle constantly with how people perceive cancer. Until a person suffers from it or sees a loved one suffer from the devastation of this disease, cancer remains an abstract term or concept. But it is an abstract concept that kills 10 million people around the world every year. Ten million people every year. How do we get people to understand that this is a lethal disease that deserves attention. That deserves more funding. That deserves more minds thinking about how to stop the continual suffering that metastatic cancer causes. Ideas often become popular long after their philosophical heyday. This seems to be the case for a cluster of ideas centring on the notion of ‘lived experience’, something I first came across when studying existentialism and phenomenology many years ago. The popular versions of these ideas are seen in expressions such as ‘my truth’ and ‘your truth’, and the tendency to give priority to feelings over dispassionate factual information or even rationality. The BBC is running a radio series entitled ‘I feel therefore I am’ which gives a sense of the influence this movement is having on our culture, and an NHS trust has apparently advertised for a ‘director of lived experience’.

Ideas often become popular long after their philosophical heyday. This seems to be the case for a cluster of ideas centring on the notion of ‘lived experience’, something I first came across when studying existentialism and phenomenology many years ago. The popular versions of these ideas are seen in expressions such as ‘my truth’ and ‘your truth’, and the tendency to give priority to feelings over dispassionate factual information or even rationality. The BBC is running a radio series entitled ‘I feel therefore I am’ which gives a sense of the influence this movement is having on our culture, and an NHS trust has apparently advertised for a ‘director of lived experience’.

Sughra Raza. Pavement Expressionism. June 2014.

Sughra Raza. Pavement Expressionism. June 2014.