by Ken MacVey

Donald Trump has creatively explored ways to monetize the presidency. These include launching the $TRUMP crypto business a few days before resuming office on January 20, 2025 or using Truth Social–a private business venture he helped start– to platform his presidential and personal pronouncements.

Monetization began early in the first Trump administration with the Trump International Hotel in Washington DC, which became, according to an October 18, 2024 House Committee on Oversight staff report, a hotel of choice for foreign and domestic influencers and would-be appointees to government positions, such as judgeships and ambassadorships. According to the report, it was also the hotel of choice for various presidential pardon recipients. This report alleged that at least five such recipients stayed at the hotel spending thousands of dollars in 2017 and 2018. The report went on: “[T]hese expenditures are particularly troubling in light of allegations that former President Trump’s former personal attorney, Rudy Giuliani, was involved in efforts to sell presidential pardons for $2 million apiece—an amount Mr. Giuliani reportedly planned to split with President Trump.” (These allegations stem from a lawsuit against Giuliani by someone who used to work for him– Giuliani denies the allegations.) Since this report, Trump has pardoned Giuliani for his role in attempting to overturn the 2020 election.

A number of Trump pardons in the last few months have caught the public’s eye. For example, in October Trump pardoned billionaire crypto entrepreneur and convicted felon, Changpeng Zhao. Zhao and his company pled guilty to failing to stop money laundering, which according to the Department of Justice aided terrorist groups like Isis. Forbes reported that Zhao’s company had made a deal in May 2025 with a Trump family affiliated company that helped boost Trump’s net worth by hundreds of millions of dollars. Liz Oyler, head pardon attorney for the Department of Justice until last March, is quoted by Forbes as saying: “Trump has created a pay-for-play pardon system.” Read more »

Let’s grant, for the sake of argument, the relatively short-range ambition that organizes much of rhetoric about artificial intelligence. That ambition is called artificial general intelligence (AGI), understood as the point at which machines can perform most economically productive cognitive tasks better than most humans. The exact timeline when we will reach AGI is contested, and some serious researchers think AGI is improperly defined. But these debates are not all that relevant because we don’t need full-blown AGI for the social consequences to arrive. You need only technology that is good enough, cheap enough, and widely deployable across the activities we currently pay people to do.

Let’s grant, for the sake of argument, the relatively short-range ambition that organizes much of rhetoric about artificial intelligence. That ambition is called artificial general intelligence (AGI), understood as the point at which machines can perform most economically productive cognitive tasks better than most humans. The exact timeline when we will reach AGI is contested, and some serious researchers think AGI is improperly defined. But these debates are not all that relevant because we don’t need full-blown AGI for the social consequences to arrive. You need only technology that is good enough, cheap enough, and widely deployable across the activities we currently pay people to do.

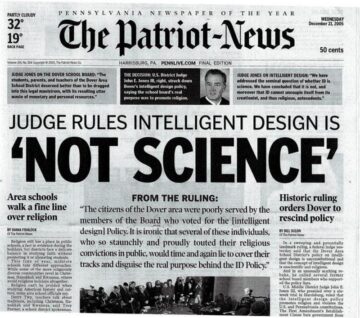

Last Saturday was the 20th anniversary of the day on which Judge John Jones III handed down

Last Saturday was the 20th anniversary of the day on which Judge John Jones III handed down

If poets are to take Imlac’s advice – and I’m not necessarily sure they should – then the proper season for doing so must be winter. No streaks of the tulip to distract us, and the verdure of the forest has been restricted to a very limited palette. Then the snow comes, and the world becomes a suggestion of something hidden, accessible only to memory or anticipation, like a toy under wrapping. Perhaps “general properties and large appearances” are accessible to us only as we gradually delete the details of life; we certainly don’t seem to have much access to them directly. This is knowledge by negation; winter is the supreme season for apophatic thinking.

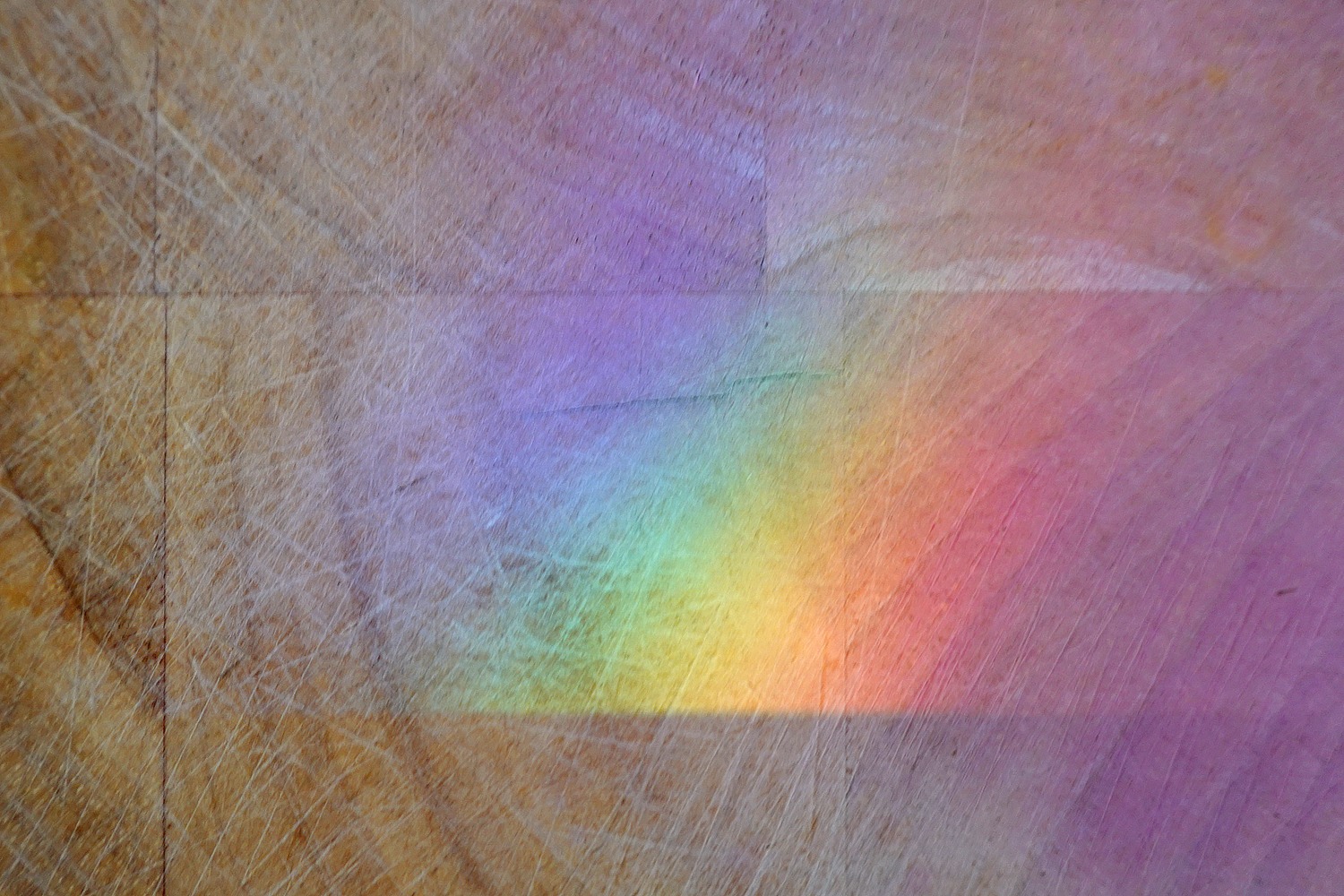

If poets are to take Imlac’s advice – and I’m not necessarily sure they should – then the proper season for doing so must be winter. No streaks of the tulip to distract us, and the verdure of the forest has been restricted to a very limited palette. Then the snow comes, and the world becomes a suggestion of something hidden, accessible only to memory or anticipation, like a toy under wrapping. Perhaps “general properties and large appearances” are accessible to us only as we gradually delete the details of life; we certainly don’t seem to have much access to them directly. This is knowledge by negation; winter is the supreme season for apophatic thinking. Sughra Raza. Underbelly Color and Shadows. Santiago, Chile, Nov, 2017.

Sughra Raza. Underbelly Color and Shadows. Santiago, Chile, Nov, 2017.

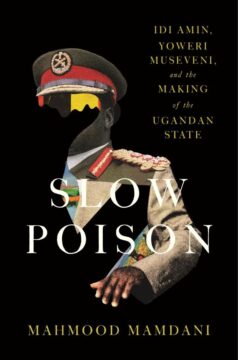

In June 1976, an Air France flight from Tel Aviv to Paris was hijacked by members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine along with two German radicals, diverted to Entebbe, Uganda, and received with open support from Idi Amin. There, the hijackers separated the passengers—releasing most non-Jewish travelers while holding Israelis and Jews hostage—and demanded the release of Palestinian prisoners. As the deadline approached, Israeli commandos flew secretly to Entebbe, drove toward the terminal in a motorcade disguised as Idi Amin’s own and stormed the building. In ninety minutes, all hijackers and several Ugandan soldiers were killed, 102 hostages were freed, and three died in the crossfire. The only Israeli soldier lost was the mission commander, Yoni Netanyahu.

In June 1976, an Air France flight from Tel Aviv to Paris was hijacked by members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine along with two German radicals, diverted to Entebbe, Uganda, and received with open support from Idi Amin. There, the hijackers separated the passengers—releasing most non-Jewish travelers while holding Israelis and Jews hostage—and demanded the release of Palestinian prisoners. As the deadline approached, Israeli commandos flew secretly to Entebbe, drove toward the terminal in a motorcade disguised as Idi Amin’s own and stormed the building. In ninety minutes, all hijackers and several Ugandan soldiers were killed, 102 hostages were freed, and three died in the crossfire. The only Israeli soldier lost was the mission commander, Yoni Netanyahu.