by Thomas R. Wells

According to the meta-charity GiveWell, the most effective charities can save a child’s life for between 3 and 5,000 US dollars. One way of understanding this figure is that whenever you consider spending that amount of money, one of the things you would be choosing not to spend it on is saving a child’s life.

According to the meta-charity GiveWell, the most effective charities can save a child’s life for between 3 and 5,000 US dollars. One way of understanding this figure is that whenever you consider spending that amount of money, one of the things you would be choosing not to spend it on is saving a child’s life.

Take the median of the GiveWell figures: $4,000. I propose that prices for all goods and services should be listed in the universal alternative currency of percentage of a Child’s Life Not Saved (%CLNS), as well as their regular prices in Euros, dollars, or whatever. For example, a Starbucks Frappucino might be priced at 5$ /0.13%CLNS. A Caribbean holiday cruise might be priced at $8,000/ 200%CLNS.

The justification for this would be to fix a gap in the way the price system functions. Normally we make our consumption decisions entirely in terms of a consideration of how much we want something and how much we can afford, a matter of prudence only. As economists have analysed, such exercises in constrained maximisation are all we need do to enjoy a flourishing economy since by responding to prices we automatically take into account the social cost to others of resources being used for what we want rather than for something else (so long as some wise and non-self-interested government steps in to correct for externalities).

Occasionally it is questioned whether merely responding rationally to the information revealed by prices is enough. For example, perhaps we should also be pushed to take account of the impact of our choices on non-human entities by explicit ethical warnings on animal products (previously).

Publishing prices in percentage Child Lives Not Saved is intended to correct a different gap in the information that prices communicate. There are many people whose needs are left out of the information communicated by market prices because they are not economically significant enough for their interests about how the world’s resources are used to compete with ours. They are literally too poor to matter to the world economy, and so we will not notice that we are neglecting their needs unless our attention is specifically drawn to that point.

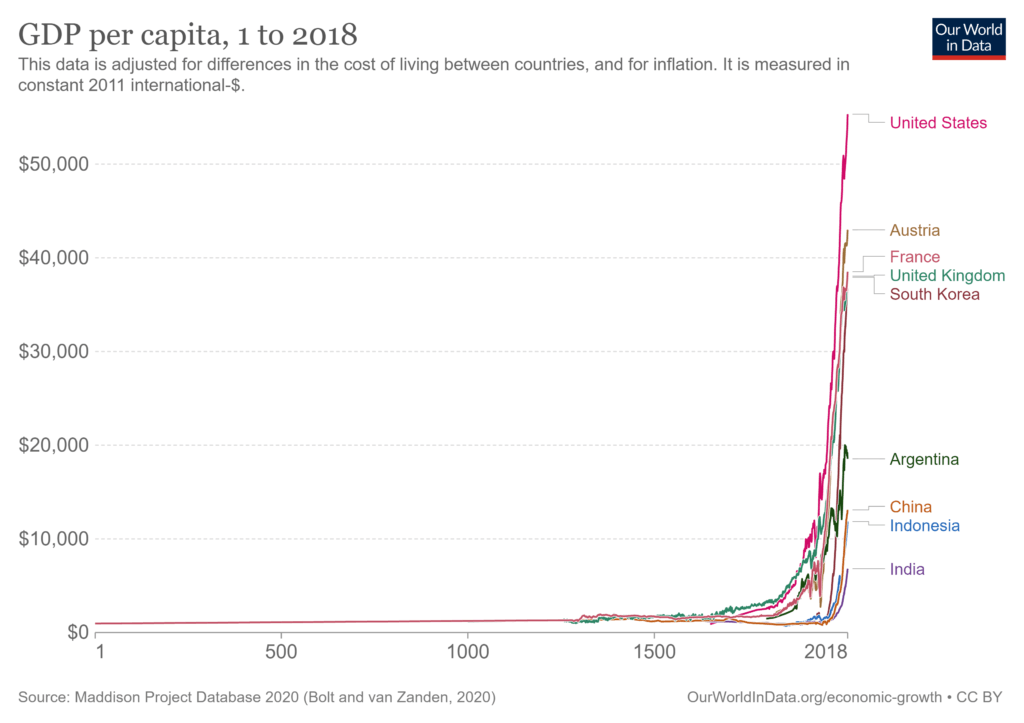

The invisibility of the poor is a consequence of global inequality. In itself there is nothing wrong with global inequality, which results merely from the fact that different countries have managed to different degrees to institutionalise the market focused rules and rights that generate economic growth and have made so much of the world so very rich over the past 200 years. People in rich countries should not be ashamed that we are rich while others are poor, for our wealth has not come at the expense of the poor (as the exploitation theorists mistakenly claim – previously). But we should be ashamed for acting as if the poor don’t exist.

An unfortunate consequence of global inequality is that the needs of the poorest people in the world are drowned out by the better-funded but less important interests of the rich. Even our cows and SUVs are ranked higher in the economic status system that determines the distribution of the world’s grain than the hunger of the world’s poor. Setting prices in the universal alternative currency of Child Lives Not Saved is an important – if crude – way of reminding all of us of the existence of the needs of the global poor and how they relate to our own choices. Whether we act on those needs remains up to us.

Thomas Wells teaches philosophy in the Netherlands and blogs on philosophy, politics, and economics at The Philosopher’s Beard