by Leanne Ogasawara

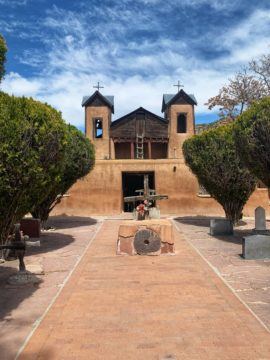

1. El Santuario de Chimayó

We arrived in Chimayó in the lull after Easter. Nestled in the foothills of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, the small hamlet lies about forty-five minutes north of Santa Fe. If I hadn’t seen videos of the great crowds that throng the sanctuary during Holy Week, I wouldn’t have believed this humble adobe church in the middle of nowhere could be the host of the largest number of religious pilgrims in the U.S—but that is what it is.

Known as the “Lourdes of North America,” many come in search of a cure—for as an old woman says, in Willa Cather’s 1927 novel Death Comes for the Archbishop, the mud is known for its medicinal qualities:

Once upon a time, the world was full of miracles.

Chances are you will meet someone suffering from illness or from a broken heart in Chimayó. In our BnB, we met a gentleman whose wife had fought cancer for a decade. She loved visiting the church and praying with the friar. And now that she is gone, her husband comes alone with his memories. For him, Chimayó has been a place of sanctuary that gives voice to his pain, which is perhaps a kind of miracle…

The day we were there, the church was in the deep shadows of the afternoon light. We sat several rows behind an elderly woman who was praying the rosary, while her grandchildren waited patiently in the nearby pew. The woman’s gaze was steady on the six-foot-tall wooden statue behind the altar. An artifact “not made by human hands,” the legend has it that it was discovered two-hundred years ago by a prominent member of the local pentinente brotherhood. Noticing a light beaming out of one of the hills near the Santa Cruz River in Chimayo, Don Bernardo Abeyta discovered the large wooden statue of Christ on the Cross lying in the dirt. He immediately petitioned the authorities to be allowed to build a chapel over the miraculous spot.

As we sat deep in our own thoughts, the woman finished her prayers and nodded to the young people, who sprang up to help her to her feet. The three then walked slowly toward the tiny room with its very low ceiling off the chancel, where they would gather holy dirt from el pocito, or “the little well.”

Despite the fact that the village is hardly mentioned in Willa Cather’s novel, it embodies what was so unique about the period of time in which the novel takes place. The book opens in a Roman garden in the summer of 1848, when Mexico had been forced to relinquish some 55% of its territory to the United States, under the terms of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. In the novel, three cardinals and a missionary bishop from America sit down over a lavish meal to discuss what is to be done with this vast new territory. Prior to this, the Spanish colonialists had allowed Catholicism to lapse in that part of their realm–especially after the Pueblo Revolt of 1680: an event which one of our guides in Santa Fe reminded us was the only time colonialists were entirely pushed out of North America by a native population.

Because the territory was vast and there were simply not enough priests to perform the rites of the liturgy in that sprawling and rough part of the new continent, lay people stepped into the vacuum left by the departing Spanish priests. Known as the Penitente, the brotherhoods (hermandad) had their origins in the Spanish flagellants. In addition to sometimes bloody self-flagellating processions during Holy Week, their rituals included mock crucifixions, solemn rituals and haunting music known as alabados.

Willa Cather depicted this extreme religious tradition in her novel with obvious distaste– because dealing with this rogue group was one of her hero’s main challenges.

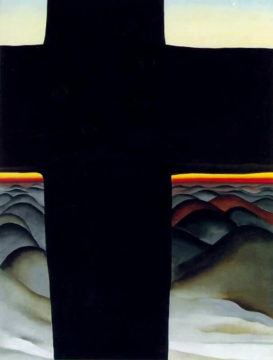

As an aside, this spiritual tradition greatly attracted Georgia O’Keeffe when she moved to Abiquiu. She would describe her paintings of the large penitente crosses, which seemed to appear and disappear in the New Mexican landscape, in letters to Alfred Stiglitz back in New York City. Some historians consider the possibility that the penitentes had their roots in the Jewish Sephardic world. In the mind-bogglingly traumatic story of the Jewish community forced out of Spain under Ferdinand and Isabella in the late 15th century, many of the refugees ended up in the New World. Hoping for freedom to live their lives in peace, they had traveled West, starting with Columbus, only to be followed to the New World by the Inquisition, which was much more deadly in the colonies. And so, to try and stay alive, some historians suggest they took on the practices of the Penitente—at the same time, carrying on with Jewish practices, like lighting candles on Friday evenings.

Fact is stranger than fiction?

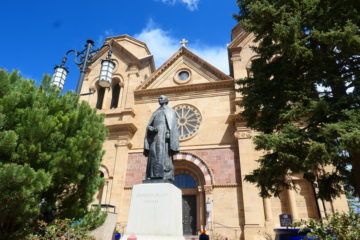

2. The Cathedral Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi in Santa Fe

In a letter Willa Cather wrote to the editor of Commonweal, she explained how she was partly inspired to write Death Comes for the Archbishop after seeing a series of fresco paintings in the Panthéon in Paris, in 1902. Painted by the great 19th century muralist Puvis de Chavannes, The Pastoral Life of Saint Geneviève (1874-79) depicts the life of the Patron Saint of Paris, Saint Geneviève, in eight panels –two triptychs and two independent pictures.

Perhaps because he was not influenced by the Impressionism of his day, Puvis’ work now seems somehow old-fashioned –a throwback, almost. But he was much admired by the avant-garde painters of his day, including Toulouse-Lautrec, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Matisse and Picasso.

It’s not clear what moved Willa Cather so much about the murals, but she would tell the editor of Commonweal that she wanted to create in prose something like what she saw in the murals: “Something without accent…” And: “something in the style of legend, which is absolutely the reverse of dramatic treatment.” In a time that values plots with conflict and character arcs, Cather was doing something unusual in her literary project to paint a picture of a legendary figure, using mood and atmosphere to tell the story.

Death Comes for the Archbishop is the story of Archbishop Latour, who is—of course—Santa Fe’s legendary Bishop Jean-Baptiste Lamy. A Frenchman by birth, Lamy was the first apostolic vicar for the New Mexico territory, after the United States acquired the territory from Mexico, in 1848. Back then, Santa Fe was in the middle of nowhere. Unable to travel on the Santa Fe Trail, because it is under attack by Indians and too dangerous, Lamy is unable to get a clear answer about how he is supposed to get to the remote town on the frontier. Finally, someone tells him to travel by boat down the Mississippi River and then “find your way to Galveston.” From there, it would be straight up the Camino de Real to Santa Fe.

And this is just what he does. But when he finally arrives in the city after nearly a year of traveling, he learns that the letters from his superiors never made it. Knowing he cannot take control of anything without the proper papers, he has to turn right back around and head back down to Camino de Real to Durango, where the church authorities are still in residence.

There is a wonderful study for the murals that Puvis did in oil—now kept at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam—which shows the young Saint Geneviève on her knees in prayer. She is in an Arcadian landscape deep in prayer as her parents look on in wonder. Will Cather’s novel has a similar scene in chapter one when we find our hero in the desert, in prayer in front of a miraculous juniper tree that resembles a cross:

“A young priest at his devotions; and a priest in a thousand, one knew at a glance. His bowed head was not that of an ordinary man—it was built for the seat of a fine intelligence. His brow was open, generous, reflective, his features handsome and somewhat severe. There was a singular elegance about the hands below the fringed cuffs of the buckskin jacket. Everything showed him to be a man of gentle birth—brave, sensitive, courteous. His manners, even when he was alone in the desert, were distinguished. He had a kind of courtesy toward himself, toward his beasts, toward the juniper tree, before which he knelt, and the God whom he was addressing.”

For me, Lamy is an unexpected hero. History books show him as being far less sympathetic to the native populations than in Cather’s novel.

He is best-known in Santa Fe for his cathedral, completed in 1887. The new cathedral was built around the former adobe church and, when the new walls were complete, the old church was torn down and removed through the front door. One part of the old adobe church was incorporated into Lamy’s stone cathedral in the form of the small chapel that houses the much-loved wooden statue La Conquistadora. Reminiscent of La Virgen de la Macarena in Seville, La Conquistadora is the oldest statue of the Virgin Mary in North America.

Though made of local stone, Lamy’s cathedral was built in the style of the cathedrals in Midi-France, where the priest was born. To manage such a task out on the frontier, Lamy brought French architects and Italian stonemasons to New Mexico to build his Romanesque Cathedral. Anyone who has visited Santa Fe will understand that this was an act of great will and intention. Lamy came to Santa Fe, after all, to bring the “real Catholicism” to this land where the religion had lapsed and superstition was on the rise. In Cather’s book, however, the cathedral is depicted as a way for Lamy to harmonize the Old World with the New. But this is what has drawn the most criticism to the novel in modern times, since of course, so much harm and destruction occurred.

And what are we to make of her depiction of Padre Martinez?

3. San Francisco de Asis Church | Ranchos de Taos

At the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, where I live, you can see a small-scale copy in oil of Puvis’ Pastoral Life of Saint Geneviève (1874-79) murals in the form of a triptych. Not surprisingly perhaps, Death Comes for the Archbishop has also been described as a painterly triptych—or even as a triple triptych!

If that is the case, I would suggest that, while the central painting in the triptych is that of Lamy’s magnificent stone cathedral, the first painting of the novel’s triptych is of the little church in Chimayó. And no two churches could be more different. Like looking at a mural painting—or even more like a Southern Song Landscape with its moving perspective, a sense of progression in Cather’s novel is not created by character arc or plot but by movement across painted landscapes. The writing is astonishingly beautiful—especially of the light-filled and other-worldly landscape of Northern New Mexico. James Woods, in his book How Fiction Works, once declared the ending chapter to be among the most beautiful ever written in the English language. And I tend to agree.

But what to do about Padre Martinez? A powerful priest who lived in Taos, he was to be the villain of the novel.

And for whatever reason, she chose to use his real name.

To get to Taos, we took the artist’s path. The “High Road to Taos,” is the stuff of legend. Fray Angelico Chavez, a highly respected historian and priest (you can see his bronze statue in front of the public library in Santa Fe) in his book My Penitente Land, compares the Land of Enchantment in Northern New Mexico to Palestine and Jerusalem; as well as to Castille, Spain and the southern region of Andalucía. His own ancestors hailed from Spain and arrived like so many others as settlers, coming up the Camino de Real with the Conquistadors. In Chavez’ story, Northern New Mexico existed as a kind of New Jerusalem for the Spanish.

I had a different reaction, however. As driving along the High Road to Taos, I could not get over how much it reminded me of Highway One in India, the road that travels into the Himalaya from Kashmir into Ladakh. Heading toward snow-capped peaks, the narrow road clings to the side of the mountain. And there are small enclaves along the way—each with its own mission church and morada, the small gathering houses for the pentinete brotherhoods. It really felt like we were on the “Road to Shambhala…”

While Taos is not at a higher elevation than Santa Fe, it feels remote and ethereal. With its low muddy-color adobe buildings, Taos stands in a valley of apricot and cottonwood trees. In addition to the 1,000-year-old Taos Pueblo, the town is famous for the San Francisco de Asis Church. You will recognize the church instantly, as it has been painted and photographed by many artists– from by Georgia O’Keeffe to Ansel Adams.

And what a church it is! Where the humble chapel in Chimayó was built to commemorate a miracle and Lamy’s stone cathedral to impress the faithful, the adobe church in Ranchos de Taos seems to have sprung up from the earth itself. The appeal is not just visual either, as the church is fragrant of earth. The congregation performs the “enjarre” –or re-plastering– each year. In this way creating the church anew in centuries of human hands…

It was here in Taos at the church that Padre Martinez was running things, when Bishop Lamy arrived in Santa Fe.

In fact, you can find a statue commemorating Martinez’s contribution in the center of town.

Wait, is this the same “swarthy” and dastardly priest from Cather’s novel, who was depicted as seducing young girls and profiting from the rebellions against the Americans?

Martinez was not the only historical character whose real name was used—as Kit Carson was also a character in the novel. And there have been complaints about her whitewashing of Kit Carson. But her treatment of Padre Martinez is hard to understand; for the real Martinez is celebrated in Taos for his work to educate children. He founded the first-co-educational school and brought a printing press to Taos to publish educational books and religious tracts. But Lamy took issue with his approach to the religion and eventually had him ex-communicated.

History is written by the victors. But it is also written by novelists… Pity the descendants of the maligned padre who have to go around trying to clear his name.

In many ways, Death Comes for the Archbishop is told like a medieval morality play. The saintly Bishop is there to bring the Good News and to do Good Works. Then we have the dastardly Padre Martinez, who represents a lack of order and failure of love. What is so interesting about Willa Cather is that she is not a Roman Catholic. Not raised as one and very vocal about her intentions to never become one. She was– surprise, surprise– an Episcopalian.

And interestingly, more than Padre Martinez, Cather places much blame on Protestant capitalism, slavery and the relentless push to modernize above all else. A famous scene from the novel takes place over a bowl of soup his dearest friend has made, when Lamy meditates on the strength and beauty of living tradition in his comment that, “No one else for thousands of miles could serve such a soup.” He then adds, “I am not depreciating your talent, but when one thinks of it a soup like this is not the work of one man. It is the result of a constantly refined tradition. There are nearly a thousand years of history in this soup.”

In the end, her novel was an expression of resistance to the mass-produced, to materialism and the disappearance of culture. ‘The longer I stayed in the Southwest,” she wrote in a letter after the novel appeared, ”the more I felt that the story of the Catholic Church in that country was the most interesting of all its stories. The old mission churches, even those which were abandoned and in ruins, had a moving reality about them; the handcarved beams and joists, the utterly unconventional frescoes, the countless fanciful figures of the saints, no two of them alike, seemed a direct expression of some very real and lively human feeling.”

Talk about the middle of nowhere, in West Texas I took a few photos of the famous art installation outside of Marfa, called Marfa Prada. A permanent art installation by Scandanavian artists Elmgreen and Dragset, the “Prada Shop in the middle of nowhere” is a statement about our out-of-control consumerism. When I posted a picture on Facebook, a friend remarked that these kinds of artistic statements that aim to critique consumerism in this way are really part of the problem. “The only way to escape consumerism is to move to Laos,” he said.

This desire to recapture a more primitive ”blood-consciousness” in order to combat materialism was one of the main reasons that drew DH Lawrence to the area. And like Cather, I too felt moved by the old mission churches, many—as she said, “abandoned and in ruins.” The handcarved wooden bultos (statues) and extraordinary retablos (paintings on wood) were very exciting. Very alive. The building material itself– the abode—is porous like human skin, it seems to breathe.

As a Californian, I always think that America’s only history is in the East—in Boston, for example. But Santa Fe is the oldest capital city in the United States. Its unique Pueblo and Hispanic culture goes all the way back to the late 16th century. As Anthony Bourdain once said, it stands as “a metaphor for America—with its Spanish- Mexican- Original American mix –with a tinge of radioactivity…” My kinda place…?