by Michael Liss

I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so. —Abraham Lincoln, First Inaugural Address, March 4, 1861

Did we need to have a Civil War? Couldn’t the two sides, geographically defined as they were, simply part before the shooting started? Did Lincoln intentionally choose war for any one of a variety of unworthy reasons that stopped short of necessity, including even something so mundane as a fear of losing face? Or was he faced with an intractable situation for which there was no simple, satisfactory answer—a type of political Trolley Problem?

Did we need to have a Civil War? Couldn’t the two sides, geographically defined as they were, simply part before the shooting started? Did Lincoln intentionally choose war for any one of a variety of unworthy reasons that stopped short of necessity, including even something so mundane as a fear of losing face? Or was he faced with an intractable situation for which there was no simple, satisfactory answer—a type of political Trolley Problem?

These questions were suggested by the recent comments from a 3 Quarks Daily reader to a 2020 article by Thomas Wells. While I don’t agree with the premise of Lincoln’s “culpability,” it is an issue that has been continuously debated by historians and opinion writers almost from the moment South Carolina forces shelled Union soldiers led by Major Robert Anderson at Fort Sumter.

In fact, the debate raged both in public and behind closed doors even before the South Carolinians reduced the Fort on April 12-13, 1861. Depending on who does the telling, either Lincoln shrewdly baited the Confederates into firing on Fort Sumter, thus unifying much of the North for a shooting war, or belligerent South Carolina fired on Fort Sumter without good cause, thus unifying much of the North for a shooting war. If you are interested, I’d recommend James D. Randall’s discussion in his 1945 Lincoln The President, but, in either telling, at the end of the day, the war that followed Sumter was not inevitable, but the product of both sides’ choices. Read more »

The first video portapacks arrived in the 1970s, cameras that skipped the lab and allowed the cameraman to be mobile, but they were so expensive only those who had connections with a TV station could experiment with them. Or if you had a rich aunt who needed to document a wedding, sometimes exorbitant rentals were available. Those with the ties to TV stations became the pioneers of art video. The rest of us painfully wove our laurels out of what could be cadged or granted. The tech, always changing, improved year by year, as did access and the imagery. We were offered new ways to think about color, resolution, and the translation of experience to video. Seeing invention at work as each new video tool appeared – sometimes developed by the artists themselves – was thrilling.

The first video portapacks arrived in the 1970s, cameras that skipped the lab and allowed the cameraman to be mobile, but they were so expensive only those who had connections with a TV station could experiment with them. Or if you had a rich aunt who needed to document a wedding, sometimes exorbitant rentals were available. Those with the ties to TV stations became the pioneers of art video. The rest of us painfully wove our laurels out of what could be cadged or granted. The tech, always changing, improved year by year, as did access and the imagery. We were offered new ways to think about color, resolution, and the translation of experience to video. Seeing invention at work as each new video tool appeared – sometimes developed by the artists themselves – was thrilling.

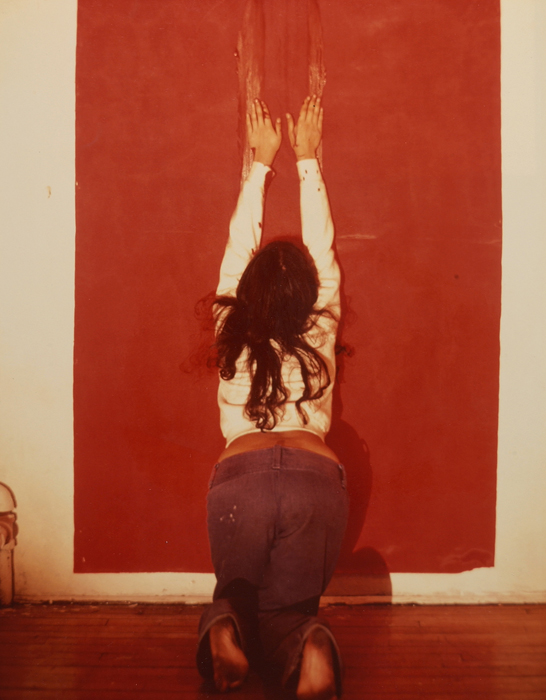

Ana Mendieta. Body Tracks, 1974.

Ana Mendieta. Body Tracks, 1974.

I recently binge-watched all of

I recently binge-watched all of

The Balkans isn’t everybody’s first choice for summer holiday, but that’s where we’re headed this year. First we’re flying to Chișinău, while we still can, and I don’t mean to be flip. Forgive my wavering confidence in Western guarantors of freedom, democracy and territorial integrity.

The Balkans isn’t everybody’s first choice for summer holiday, but that’s where we’re headed this year. First we’re flying to Chișinău, while we still can, and I don’t mean to be flip. Forgive my wavering confidence in Western guarantors of freedom, democracy and territorial integrity.

Why do we enjoy showing and sharing?

Why do we enjoy showing and sharing? A theory developed by

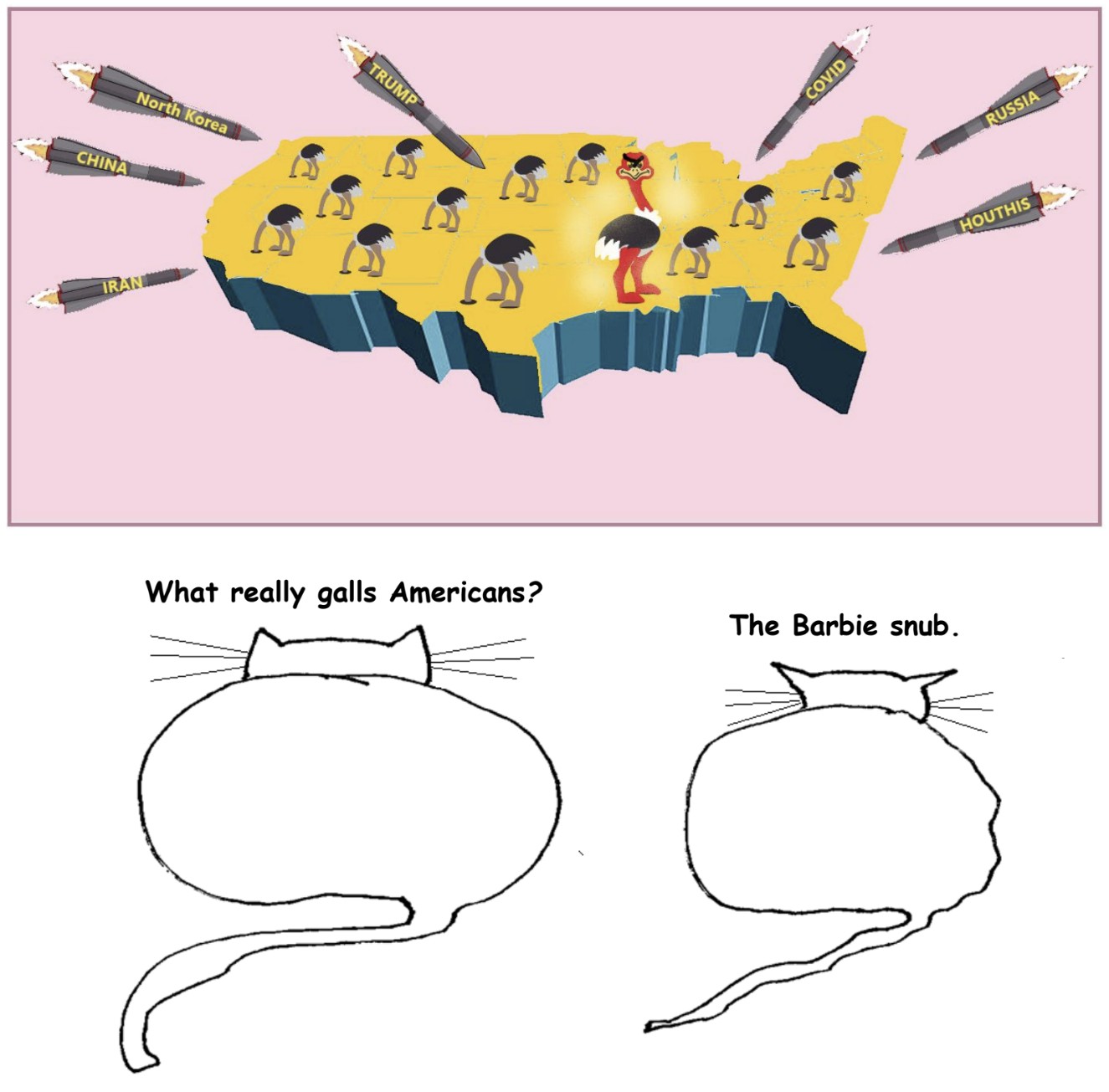

A theory developed by  One unfortunate feature of American politics is that both Republicans and Democrats tend to work themselves into a frenzy over the other party’s presidential candidate, no matter who it is. To put it bluntly, both sides cry wolf all the time. Yes, I am a Democrat, but Democrats do this too — I’m old enough to remember when people I knew went crazy over poor old Mitt Romney saying that he had “

One unfortunate feature of American politics is that both Republicans and Democrats tend to work themselves into a frenzy over the other party’s presidential candidate, no matter who it is. To put it bluntly, both sides cry wolf all the time. Yes, I am a Democrat, but Democrats do this too — I’m old enough to remember when people I knew went crazy over poor old Mitt Romney saying that he had “ Greetings, gentle readers! Welcome to the very first installment of Am I the (Literary) Assh*le, a series where I get drunk and answer your burning (anonymous) questions about all things literary.

Greetings, gentle readers! Welcome to the very first installment of Am I the (Literary) Assh*le, a series where I get drunk and answer your burning (anonymous) questions about all things literary. On Monday, tens of millions across

On Monday, tens of millions across  There’s a scene in that modern classic of screwball existentialism,

There’s a scene in that modern classic of screwball existentialism,