Dylan Riley in Sidecar:

Du Bois’s relationship to Marxism has become a focus of considerable debate in US sociology; the stakes are at once intellectual and crypto-political. Some want to enroll Du Bois into the ranks of ‘intersectional theory’, a notion which holds that everything has exactly three causes (race, class, and gender), somewhat analogous to the way certain Weberians are dogmatically attached to a fixed set of ‘factors’ (ideological, economic, military, political). Others want to incorporate him into the tradition of Western Marxism and its signature problem of failed revolution. Broadly speaking, the first group tends to emphasize Du Bois’s earlier writings, thereby downplaying the influence of Marxism, while the second focuses on his later work, with its critiques of capitalism and imperialism and its reflections on the Soviet experiment.

But Du Bois’s masterwork, Black Reconstruction (1935), doesn’t fit either of these interpretations. The concept of ‘intersectionality’ appears nowhere, and there is no evidence that DuBois thought in these terms. Nor is Du Bois’s proletariat, or at least its most politically important part, the industrial working class; it is rather the family farmer, both in the West and the South, both black and white. Accordingly, his political ideal was ‘agrarian democracy’. He sometimes refers to those supporting this programme rather misleadingly as ‘peasant farmers’ or ‘peasant proprietors’, which might lead one to think that he is closer to ‘Populism’ in the Russian sense than to Marxism. But that too would be a misreading, for in his understanding the social foundation of democracy does not consist in a pre-capitalist village structure with collective ownership of land, but in a stratum of independent small holders (one that failed fully to appear in the South after the Civil War because of ferocious resistance by the plantocracy, which produced the amphibious figure of the share-cropper).

More here.

DURING A HISTORY

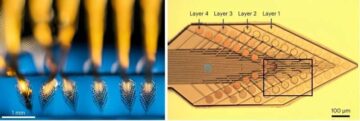

DURING A HISTORY Recording the activity of large populations of single neurons in the brain over long periods of time is crucial to further our understanding of neural circuits, to enable novel medical device-based therapies and, in the future, for brain–computer interfaces requiring high-resolution electrophysiological information. But today there is a tradeoff between how much high-resolution information an implanted device can measure and how long it can maintain recording or stimulation performances. Rigid, silicon implants with many sensors, can collect a lot of information but can’t stay in the body for very long. Flexible, smaller devices are less intrusive and can last longer in the brain but only provide a fraction of the available neural information.

Recording the activity of large populations of single neurons in the brain over long periods of time is crucial to further our understanding of neural circuits, to enable novel medical device-based therapies and, in the future, for brain–computer interfaces requiring high-resolution electrophysiological information. But today there is a tradeoff between how much high-resolution information an implanted device can measure and how long it can maintain recording or stimulation performances. Rigid, silicon implants with many sensors, can collect a lot of information but can’t stay in the body for very long. Flexible, smaller devices are less intrusive and can last longer in the brain but only provide a fraction of the available neural information. For anyone who has seen or heard Watts at his best – courtesy, perhaps, of his podcast talks – ‘immeasurably alive’ is quite a good description of the man himself. It is easy to see how a basic understanding of God in these terms might have resonated with him. Watts also had moments when the sheer wonder of life around him made it feel as though it was not merely ‘there’, as brute fact, but was being poured out with extraordinary generosity. It seemed ‘given’, convincing Watts that there must be a giver and filling him with the desire to say ‘thank you’. He found backing for all of this in the writings of the 14th-century German theologian Meister Eckhart and the 6th-century Greek author Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite. It was there, too, in the ‘I-Thou’ thought of the modern Jewish philosopher

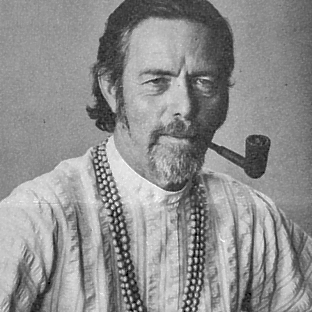

For anyone who has seen or heard Watts at his best – courtesy, perhaps, of his podcast talks – ‘immeasurably alive’ is quite a good description of the man himself. It is easy to see how a basic understanding of God in these terms might have resonated with him. Watts also had moments when the sheer wonder of life around him made it feel as though it was not merely ‘there’, as brute fact, but was being poured out with extraordinary generosity. It seemed ‘given’, convincing Watts that there must be a giver and filling him with the desire to say ‘thank you’. He found backing for all of this in the writings of the 14th-century German theologian Meister Eckhart and the 6th-century Greek author Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite. It was there, too, in the ‘I-Thou’ thought of the modern Jewish philosopher  The air conditioner was malfunctioning. When I bought the car used in January, the owner said she had just fixed it, but here I was on a steamy August day on the Atlantic coast of Senegal, with the vents pouring hot air into the already hot car. So, it was my imminent dehydration talking when I skidded to a stop in front of a roadside fruit seller’s table. I was once told by a grandmother, who lives in my seaside village but grew up in the northern dry regions where the Senegal River winds across a crispy and prickly savanna not far from the great desert, about a watermelon varietal called beref, which is cultivated mostly for its seeds but also serves as a kind of water reserve.

The air conditioner was malfunctioning. When I bought the car used in January, the owner said she had just fixed it, but here I was on a steamy August day on the Atlantic coast of Senegal, with the vents pouring hot air into the already hot car. So, it was my imminent dehydration talking when I skidded to a stop in front of a roadside fruit seller’s table. I was once told by a grandmother, who lives in my seaside village but grew up in the northern dry regions where the Senegal River winds across a crispy and prickly savanna not far from the great desert, about a watermelon varietal called beref, which is cultivated mostly for its seeds but also serves as a kind of water reserve. Why is giving birth so dangerous despite millions of years of evolution?

Why is giving birth so dangerous despite millions of years of evolution? “If China takes Taiwan, they will turn the world off, potentially,” Donald Trump

“If China takes Taiwan, they will turn the world off, potentially,” Donald Trump  DE MONCHAUX

DE MONCHAUX