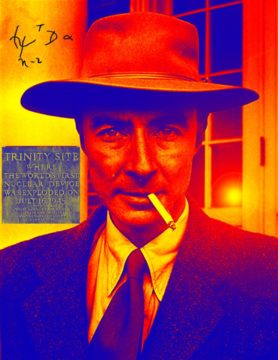

by Ashutosh Jogalekar

This is the sixth in a series of essays on the life and times of J. Robert Oppenheimer. All the others can be found here.

Colonel Leslie Groves, son of an Army chaplain who held discipline sacrosanct above anything else in life, had finished fourth in his class at West Point and studied engineering at MIT. He had excelled in the course of a long career in building and coordinating large-scale projects, culminating in his building the Pentagon, which was then the largest building under one roof anywhere in the world. In September, 1942, Groves was wrapping up and eager to get an overseas assignment when he was summoned by his superior, Lieutenant General Brehon Somervell. Somervell told Groves that he had been reassigned to an important project. When Groves irritably asked which one, Somervell told him that it was a project that could end the war. Groves had learned enough about the fledgling bomb program through the grapevine that his reaction was very simple – “Oh”.

Robert Oppenheimer is the most famous person associated with the Manhattan Project, but the truth of the matter is that there was one person even more important than him for the success of the project – Leslie Groves. Without Groves the project would likely have been impossible or delayed so much as to be useless. Groves was the ideal man for the job. By the fall of 1942, the basic theory of nuclear fission had been worked out and the key goal was to translate theory into practice. Enrico Fermi’s pioneering experiment under the football stands at the University of Chicago – effectively building the world’s first nuclear reactor – had made it clear that a chain reaction in uranium could be initiated and controlled. The rest would require not just theoretical physics but experimental physics, chemistry, ordnance and engineering. Most importantly, it would need large-scale project and personnel management and coordination between dozens of private and government institutions. To accomplish this needed the talents of a go-getter, a no-nonsense operator who could move insurmountable obstacles and people by the sheer force of his personality, someone who may not be popular but was feared and respected and who got the job done. Groves was that man and more. Read more »

Nanni Moretti has always been a melancholic in denial. Perhaps more than any other film-director raised on the French New Wave – born in 1953, shooting his first short in 1973 – Moretti has been turning around the question that François Truffaut posed as a key to the seventh art: is cinema more important than life? But where for Truffaut, or Rossellini, as for many amongst their long and glorious lineage (from Spielberg to Tran Anh Hung) the dilemma has been between a painful reality full of obstacles on one side and a ‘harmonious’ path where ‘there are no traffic jams’ (to speak like Truffaut in his 1973 Day for Night), on the other – in other words, where cinema is the path of escape towards a world where dreams (or nightmares) come true – for Moretti, it is the dilemma itself which is the essence of cinema.

Nanni Moretti has always been a melancholic in denial. Perhaps more than any other film-director raised on the French New Wave – born in 1953, shooting his first short in 1973 – Moretti has been turning around the question that François Truffaut posed as a key to the seventh art: is cinema more important than life? But where for Truffaut, or Rossellini, as for many amongst their long and glorious lineage (from Spielberg to Tran Anh Hung) the dilemma has been between a painful reality full of obstacles on one side and a ‘harmonious’ path where ‘there are no traffic jams’ (to speak like Truffaut in his 1973 Day for Night), on the other – in other words, where cinema is the path of escape towards a world where dreams (or nightmares) come true – for Moretti, it is the dilemma itself which is the essence of cinema.

Those of us who revere Octavia Butler’s work and have never stopped mourning her passing do so in part, I suspect, because we know that no matter what happens in this Universe there will never be anyone like Butler again—not as a person and certainly not as an artist. Like Toni Morrison, Butler was a literary eucatastrophe, (a sudden and miraculous grace: never to be counted on to recur), a literary Kwisatz Haderach (Butler loved Dune) that occurs so very rarely in a culture and only if it is lucky.

Those of us who revere Octavia Butler’s work and have never stopped mourning her passing do so in part, I suspect, because we know that no matter what happens in this Universe there will never be anyone like Butler again—not as a person and certainly not as an artist. Like Toni Morrison, Butler was a literary eucatastrophe, (a sudden and miraculous grace: never to be counted on to recur), a literary Kwisatz Haderach (Butler loved Dune) that occurs so very rarely in a culture and only if it is lucky.

It’s somewhat amazing that cosmology, the study of the universe as a whole, can make any progress at all. But it has, especially so in recent decades. Partly that’s because nature has been kind to us in some ways: the universe is quite a simple place on large scales and at early times. Another reason is a leap forward in the data we have collected, and in the growing use of a powerful tool: computer simulations. I talk with cosmologist Andrew Pontzen on what we know about the universe, and how simulations have helped us figure it out. We also touch on hot topics in cosmology (early galaxies discovered by JWST) as well as philosophical issues (are simulations data or theory?).

It’s somewhat amazing that cosmology, the study of the universe as a whole, can make any progress at all. But it has, especially so in recent decades. Partly that’s because nature has been kind to us in some ways: the universe is quite a simple place on large scales and at early times. Another reason is a leap forward in the data we have collected, and in the growing use of a powerful tool: computer simulations. I talk with cosmologist Andrew Pontzen on what we know about the universe, and how simulations have helped us figure it out. We also touch on hot topics in cosmology (early galaxies discovered by JWST) as well as philosophical issues (are simulations data or theory?). Ecological collapse is likely to start sooner than previously believed, according to a new study that models how tipping points can amplify and accelerate one another.

Ecological collapse is likely to start sooner than previously believed, according to a new study that models how tipping points can amplify and accelerate one another. ‘G

‘G