Tim Smedley in The Guardian:

During the summer months in the Oxfordshire town where I live, I go swimming in the nearby 50-metre lido. With my inelegantly slow breaststroke, from time to time I accidentally gulp some of the pool’s opulent, chlorine-clean 5.9m litres of water. Sometimes, I swim while it’s raining, when fewer people brave it, alone in my lane with the strangely comforting feeling of having water above and below me. I stand a bottle of water at the end of the lane, to drink from halfway through my swim. I normally have a shower afterwards, even if I’ve showered that morning. I live a wet, drenched, quenched existence. But, as I discovered, this won’t last. I am living on borrowed time and borrowed water.

During the summer months in the Oxfordshire town where I live, I go swimming in the nearby 50-metre lido. With my inelegantly slow breaststroke, from time to time I accidentally gulp some of the pool’s opulent, chlorine-clean 5.9m litres of water. Sometimes, I swim while it’s raining, when fewer people brave it, alone in my lane with the strangely comforting feeling of having water above and below me. I stand a bottle of water at the end of the lane, to drink from halfway through my swim. I normally have a shower afterwards, even if I’ve showered that morning. I live a wet, drenched, quenched existence. But, as I discovered, this won’t last. I am living on borrowed time and borrowed water.

Water stolen from nature, drained from rivers and lakes and returned polluted, allows me to live this way. It will have to stop – not through some altruistic hand-wringing desire to do better, but because even in England this amount of water will soon be unavailable.

More here.

As part of our event series with The Philosopher, Amna Akbar sat down with Bernard Harcourt, legal scholar and professor of political science at Columbia University, to discuss his new book, Cooperation: A Political, Economic, and Social Theory. In the course of their conversation, moderated by Philosopher editor Anthony Morgan, they discuss the failure of traditional electoral politics and mass mobilization, existing cooperative efforts, our punitive society, and how we might build democratic self-governance. Below is a transcript of their conversation, which has been edited for clarity and concision.

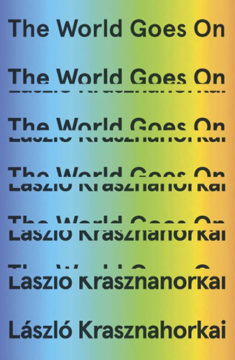

As part of our event series with The Philosopher, Amna Akbar sat down with Bernard Harcourt, legal scholar and professor of political science at Columbia University, to discuss his new book, Cooperation: A Political, Economic, and Social Theory. In the course of their conversation, moderated by Philosopher editor Anthony Morgan, they discuss the failure of traditional electoral politics and mass mobilization, existing cooperative efforts, our punitive society, and how we might build democratic self-governance. Below is a transcript of their conversation, which has been edited for clarity and concision. Hungarian writer László Krasznahorkai has become a more familiar name to English speaking readers over the last few years thanks to his receipt of the Man Booker International Prize in 2015. Nevertheless, his is a name that remains shrouded in a certain mystique, due in part to his gnomic responses in interviews, and to the notorious difficulty of his work, with its breathtakingly long sentences and apocalyptic, melancholic themes. The World Goes On, which has been shortlisted for 2018 Man Booker International Prize, continues to explore these themes, albeit in a less menacing or apocalyptic tone than some of his earlier works.

Hungarian writer László Krasznahorkai has become a more familiar name to English speaking readers over the last few years thanks to his receipt of the Man Booker International Prize in 2015. Nevertheless, his is a name that remains shrouded in a certain mystique, due in part to his gnomic responses in interviews, and to the notorious difficulty of his work, with its breathtakingly long sentences and apocalyptic, melancholic themes. The World Goes On, which has been shortlisted for 2018 Man Booker International Prize, continues to explore these themes, albeit in a less menacing or apocalyptic tone than some of his earlier works. One March day in 1742, a very unusual man set up a table on a busy Philadelphia street. Benjamin Lay was sixty-one years old, wore humble homespun clothes, and sported a long beard. His head was large and his eyes luminous, but his posture and height immediately set him apart: he had a stooped back and stood a little over four feet tall. He carefully laid out a few teacups and saucers, delicate objects that had been treasured by his wife before she passed away, and then proceeded to smash them with a hammer, crushing the dishes with dramatic flair. With each loud blow, bits of ceramic flying, he denounced the “tyrants” in India and the Caribbean who mistreated the workers who harvested the tea and enslaved the people who produced the sugar that his Pennsylvania neighbors consumed.

One March day in 1742, a very unusual man set up a table on a busy Philadelphia street. Benjamin Lay was sixty-one years old, wore humble homespun clothes, and sported a long beard. His head was large and his eyes luminous, but his posture and height immediately set him apart: he had a stooped back and stood a little over four feet tall. He carefully laid out a few teacups and saucers, delicate objects that had been treasured by his wife before she passed away, and then proceeded to smash them with a hammer, crushing the dishes with dramatic flair. With each loud blow, bits of ceramic flying, he denounced the “tyrants” in India and the Caribbean who mistreated the workers who harvested the tea and enslaved the people who produced the sugar that his Pennsylvania neighbors consumed. Temnothorax nylanderi

Temnothorax nylanderi Over the last decade, dozens of companies and nearly all large countries have vowed to stop demolishing forests, a practice that destroys entire communities of wildlife and pollutes the air with enormous amounts of carbon dioxide. A big climate conference in Glasgow, in the fall of 2021, produced the most significant pledge to date:

Over the last decade, dozens of companies and nearly all large countries have vowed to stop demolishing forests, a practice that destroys entire communities of wildlife and pollutes the air with enormous amounts of carbon dioxide. A big climate conference in Glasgow, in the fall of 2021, produced the most significant pledge to date:  T

T

Setsuko Nakamura was 13 years old when the atomic bomb hit Hiroshima.

Setsuko Nakamura was 13 years old when the atomic bomb hit Hiroshima.  The multi-prize-winning theoretical physicist Giorgio Parisi was born in Rome in 1948. He studied physics at the Sapienza University in the city, and is now a professor of quantum theories there. A researcher of broad interests, Parisi is perhaps best known for his work on “spin glasses” or disordered magnetic states, contributing to the theory of complex systems. For this work, together with Klaus Hasselmann and Syukuro Manabe,

The multi-prize-winning theoretical physicist Giorgio Parisi was born in Rome in 1948. He studied physics at the Sapienza University in the city, and is now a professor of quantum theories there. A researcher of broad interests, Parisi is perhaps best known for his work on “spin glasses” or disordered magnetic states, contributing to the theory of complex systems. For this work, together with Klaus Hasselmann and Syukuro Manabe,  The war in Ukraine has resurrected the ultimate technocratic fantasy: a winnable nuclear war. Intellectuals at the Hoover Institution are urging American strategists to “think nuclearly again,” reestablishing the idea that nuclear weapons are tools to assert U.S. primacy over Russia and China. This isn’t just talk. The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists recently noted “steadily increasing U.S. bomber operations in Europe”—some near the Russian border. Though most Americans are unaware of it, escalation toward nuclear conflict is already under way.

The war in Ukraine has resurrected the ultimate technocratic fantasy: a winnable nuclear war. Intellectuals at the Hoover Institution are urging American strategists to “think nuclearly again,” reestablishing the idea that nuclear weapons are tools to assert U.S. primacy over Russia and China. This isn’t just talk. The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists recently noted “steadily increasing U.S. bomber operations in Europe”—some near the Russian border. Though most Americans are unaware of it, escalation toward nuclear conflict is already under way. A 25-year science wager has come to an end. In 1998, neuroscientist Christof Koch bet philosopher David Chalmers that the mechanism by which the brain’s neurons produce consciousness would be discovered by 2023. Both scientists agreed publicly on 23 June, at the annual meeting of the Association for the Scientific Study of Consciousness (ASSC) in New York City, that it is still an ongoing quest — and declared Chalmers the winner. What ultimately helped to settle the bet was a key study testing two leading hypotheses about the neural basis of consciousness, whose findings were unveiled at the conference. “It was always a relatively good bet for me and a bold bet for Christof,” says Chalmers, who is now co-director of the Center for Mind, Brain and Consciousness at New York University. But he also says this isn’t the end of the story, and that an answer will come eventually: “There’s been a lot of progress in the field.”

A 25-year science wager has come to an end. In 1998, neuroscientist Christof Koch bet philosopher David Chalmers that the mechanism by which the brain’s neurons produce consciousness would be discovered by 2023. Both scientists agreed publicly on 23 June, at the annual meeting of the Association for the Scientific Study of Consciousness (ASSC) in New York City, that it is still an ongoing quest — and declared Chalmers the winner. What ultimately helped to settle the bet was a key study testing two leading hypotheses about the neural basis of consciousness, whose findings were unveiled at the conference. “It was always a relatively good bet for me and a bold bet for Christof,” says Chalmers, who is now co-director of the Center for Mind, Brain and Consciousness at New York University. But he also says this isn’t the end of the story, and that an answer will come eventually: “There’s been a lot of progress in the field.” Two new drugs for treating obesity are on course to become available in the next few years — and they offer advantages beyond those of the

Two new drugs for treating obesity are on course to become available in the next few years — and they offer advantages beyond those of the