Month: June 2023

The Science (and Pseudoscience) of Aging

Harriet Hall in Skeptical Inquirer:

Researchers have failed to find a uniform marker for aging. The aging process seems to be different for different individuals; it is varied, chaotic, and idiosyncratic. There is probably no single cause, but many causes have been proposed: collagen breakdown, UV light, oxidation, inflammation, insulin resistance, glycation, free radicals, accumulation of DNA copying errors, telomere shortening, accumulation of waste products, heterochromatin loss, and many others. I suspect that many of these factors are contributory and that they interact with each other.

Researchers have failed to find a uniform marker for aging. The aging process seems to be different for different individuals; it is varied, chaotic, and idiosyncratic. There is probably no single cause, but many causes have been proposed: collagen breakdown, UV light, oxidation, inflammation, insulin resistance, glycation, free radicals, accumulation of DNA copying errors, telomere shortening, accumulation of waste products, heterochromatin loss, and many others. I suspect that many of these factors are contributory and that they interact with each other.

Ray Kurzweil believes that science will soon discover the key to immortality, and if he can just stay alive until then, he believes he will be able to live forever. He optimistically takes 250 supplement pills a day, gets weekly IV infusions, uses acupuncture and Chinese herbs, and does other things that he thinks might help keep him alive. His approach is nothing but hope and speculation.

More here.

Biggest ever study of primate genomes has surprises for humanity

Dyani Lewis in Nature:

The largest ever study of primates has unveiled surprises about humanity and our closest relatives, providing insight into which genes do, and don’t, separate us from other primates. The huge international study has also yielded new data for a wide range of disciplines, including human health, conservation biology and behavioural science.

The largest ever study of primates has unveiled surprises about humanity and our closest relatives, providing insight into which genes do, and don’t, separate us from other primates. The huge international study has also yielded new data for a wide range of disciplines, including human health, conservation biology and behavioural science.

More than 500 species of primate exist today, including humans, monkeys, apes, lemurs, tarsiers and lorises. Many are threatened by climate change, habitat loss and illegal hunting. Researchers sequenced genomes from nearly half of all primate species, investigating more than 800 genomes from 233 species around the world, representing all 16 families of primate. The work has been published in a series of papers in Science and Science Advances this week1–10.

“The more we understand about primate genomics, the more we’ll understand about human genomics,” says primatologist Alison Behie at the Australian National University in Canberra. “There’s a potential there to do a lot more really interesting work as they grow that sample size to bring in more species.”

More here.

The Ether Dreams of Fin-de-Siècle Paris

Mike Jay in The Public Domain Review:

Those who sipped or sniffed ether and chloroform in the 19th century experienced a range of effects from these repurposed anaesthetics, including preternatural mental clarity, psychological hauntings, and slippages of space and time. Mike Jay explores how the powerful solvents shaped the writings of Guy de Maupassant and Jean Lorrain — psychonauts who opened the door to an invisible dimension of mind and suffered Promethean consequences.

Those who sipped or sniffed ether and chloroform in the 19th century experienced a range of effects from these repurposed anaesthetics, including preternatural mental clarity, psychological hauntings, and slippages of space and time. Mike Jay explores how the powerful solvents shaped the writings of Guy de Maupassant and Jean Lorrain — psychonauts who opened the door to an invisible dimension of mind and suffered Promethean consequences.

More here.

Is It Real or Imagined? How Your Brain Tells the Difference

Yasemin Saplakoglu in Quanta:

Is this the real life? Is this just fantasy?

Is this the real life? Is this just fantasy?

Those aren’t just lyrics from the Queen song “Bohemian Rhapsody.” They’re also the questions that the brain must constantly answer while processing streams of visual signals from the eyes and purely mental pictures bubbling out of the imagination. Brain scan studies have repeatedly found that seeing something and imagining it evoke highly similar patterns of neural activity. Yet for most of us, the subjective experiences they produce are very different.

“I can look outside my window right now, and if I want to, I can imagine a unicorn walking down the street,” said Thomas Naselaris, an associate professor at the University of Minnesota. The street would seem real and the unicorn would not. “It’s very clear to me,” he said. The knowledge that unicorns are mythical barely plays into that: A simple imaginary white horse would seem just as unreal.

So “why are we not constantly hallucinating?” asked Nadine Dijkstra, a postdoctoral fellow at University College London.

More here.

Escape from the Market

Simon Torracinta in the Boston Review:

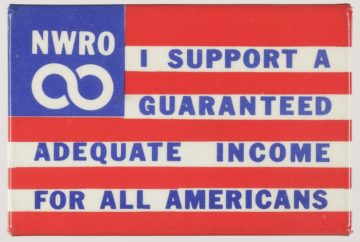

Dreams of a guaranteed income are longstanding, but they leapt back into the public imagination in the wake of the dismal recovery from the 2008 financial crash, endorsed by a diverse array of figures on both the left and right. In 2020 presidential candidate Andrew Yang briefly managed to catapult himself into the media spotlight by pitching an eye-catching “Freedom Dividend” of $1,000 a month to every U.S. citizen over the age of eighteen. Building on this momentum, the massive social and economic dislocation of the pandemic and the nearly unprecedented use of fiscal firepower seemed poised to effect a permanent transformation of the welfare system in both the United States and across much of the Global North.

Dreams of a guaranteed income are longstanding, but they leapt back into the public imagination in the wake of the dismal recovery from the 2008 financial crash, endorsed by a diverse array of figures on both the left and right. In 2020 presidential candidate Andrew Yang briefly managed to catapult himself into the media spotlight by pitching an eye-catching “Freedom Dividend” of $1,000 a month to every U.S. citizen over the age of eighteen. Building on this momentum, the massive social and economic dislocation of the pandemic and the nearly unprecedented use of fiscal firepower seemed poised to effect a permanent transformation of the welfare system in both the United States and across much of the Global North.

Yet as soon as the drastic recovery measures began to revive the U.S. growth engine and inflation began to tick upward as snarled supply chains creaked under new waves of consumer demand, a chorus of economists and employers began to scream that the emergency measures were responsible for overheating the economy. Today inflation anxiety continues to dominate headlines, the impact payments have entirely stopped, and every pandemic-era expansion of the transfer system has been allowed to quietly expire.

More here.

Yoshua Bengio & Yuval Noah Harari: Artificial Intelligence, Democracy, & the Future of Civilization

Oscar Levant

Dixie Burge in Big Band Swing:

“Oscar Levant is a character who, if he did not exist, could not be imagined.” These words were used by Levant’s great friend, S. N.(“Sam”)Behrman, to describe him. No truer words were ever spoken! In his lifetime, Oscar Levant flourished as (and subsequently gave up each, one by one) gifted composer, concert pianist, radio personality, movie star, successful recording artist, best-selling author, talk-show host and quiz show panelist. Whew! It was what he described as his Noel Coward Principal he managed “to break off his jobs at a certain interval.” He appeared in thirteen movies, including “An American In Paris”, “The Band Wagon”, “Humoresque” and the George Gershwin biograpy, “Rhapsody in Blue”, in which he played “an unsympathetic part… myself.”

“Oscar Levant is a character who, if he did not exist, could not be imagined.” These words were used by Levant’s great friend, S. N.(“Sam”)Behrman, to describe him. No truer words were ever spoken! In his lifetime, Oscar Levant flourished as (and subsequently gave up each, one by one) gifted composer, concert pianist, radio personality, movie star, successful recording artist, best-selling author, talk-show host and quiz show panelist. Whew! It was what he described as his Noel Coward Principal he managed “to break off his jobs at a certain interval.” He appeared in thirteen movies, including “An American In Paris”, “The Band Wagon”, “Humoresque” and the George Gershwin biograpy, “Rhapsody in Blue”, in which he played “an unsympathetic part… myself.”

…Levant was an astonishingly gifted concert pianist who, in his heyday of the 1940’s and early-to-mid 1950’s, earned more money than any other pianist in America. In the 1930’s, before he gained his real fame, Levant was dubbed “the wag of Broadway” by Michael Mok in the New York Post. In the 1940’s, at the height of his fame as a wit and bad boy, he was known as “the enfant terrible.” In the 1950’s and ‘60’s, after mental illness and drug abuse had taken their toll, Levant was known as “America’s favorite neurotic.” He sporadically appeared on The Tonight Show with Jack Paar to talk candidly about those subjects, being the first well-known personality to do so. He coined a now-famous phrase: “There is a fine line between genius and insanity. I have erased that line.” Author Christopher Isherwood described Levant as a character created by Dostoevsky someone “completely unmasked at all times.”

…“It’s not what you are – it’s what you don’t become that hurts.” Oscar Levant

More here.

Is memory relational or absolute?

Daniel Levitin in Delancey Place:

“The big debate among memory theorists over the last hundred years has been about whether human and animal is relational or absolute. The relational school argues that our memory system stores information about the relations between objects and ideas, but not necessarily details about the objects themselves. This is also called the constructivist view, because it implies that, lacking sensory specifics, we construct a memory representation of reality out of these relations (with many details filled in or reconstructed on the spot). The constructivists believe that the function of memory is to ignore irrelevant details, while preserving the gist. The competing theory is called the record-keeping theory. Supporters of this view argue that memory is like a tape recorder or digital video camera, preserving all or most of our experiences accurately, and with near perfect fidelity.

“The big debate among memory theorists over the last hundred years has been about whether human and animal is relational or absolute. The relational school argues that our memory system stores information about the relations between objects and ideas, but not necessarily details about the objects themselves. This is also called the constructivist view, because it implies that, lacking sensory specifics, we construct a memory representation of reality out of these relations (with many details filled in or reconstructed on the spot). The constructivists believe that the function of memory is to ignore irrelevant details, while preserving the gist. The competing theory is called the record-keeping theory. Supporters of this view argue that memory is like a tape recorder or digital video camera, preserving all or most of our experiences accurately, and with near perfect fidelity.

“Music plays a role in this debate because — as the Gestalt psychologists noted over one hundred years ago — melodies are defined by pitch relations (a constructivist view) and yet, they are composed of precise pitches (a record-keeping view, but only if those pitches are encoded in memory).

More here.

Christine and the Queens’ Restless Self-Inventions

Hanif Abdurraqib at The New Yorker:

In 2014, Christine and the Queens’ French album début, “Chaleur Humaine” (“Human Warmth”), became a runaway hit; the following year, a self-titled version appeared in the U.S., with many of the lyrics reworked into English. The songs had infectious hooks and shimmering electronic instrumentation. Back then, Letissier used feminine pronouns, but he was already casting off the strictures of gender. The opening song of the début album, “iT,” was a danceable tune in which bright drops of synthesizer rained into caverns of pulsating bass. The lyrics were a priapic fantasy: “I’ll rule over all my dead impersonations / ’Cause I’ve got it / I’m a man now.” I saw Christine and the Queens perform in 2015, in New York, and recall how hard-earned those declarations seemed to be. Christine—petite, lithe, androgynous—seemed at ease in a dark suit, standing at the front of the stage or dancing in a wash of blue light. But there were moments when the line between Letissier’s different selves blurred. During one rapturous wave of applause, he teared up, then apologized for the lapse, admitting, “I wanted to be fierce.”

In 2014, Christine and the Queens’ French album début, “Chaleur Humaine” (“Human Warmth”), became a runaway hit; the following year, a self-titled version appeared in the U.S., with many of the lyrics reworked into English. The songs had infectious hooks and shimmering electronic instrumentation. Back then, Letissier used feminine pronouns, but he was already casting off the strictures of gender. The opening song of the début album, “iT,” was a danceable tune in which bright drops of synthesizer rained into caverns of pulsating bass. The lyrics were a priapic fantasy: “I’ll rule over all my dead impersonations / ’Cause I’ve got it / I’m a man now.” I saw Christine and the Queens perform in 2015, in New York, and recall how hard-earned those declarations seemed to be. Christine—petite, lithe, androgynous—seemed at ease in a dark suit, standing at the front of the stage or dancing in a wash of blue light. But there were moments when the line between Letissier’s different selves blurred. During one rapturous wave of applause, he teared up, then apologized for the lapse, admitting, “I wanted to be fierce.”

more here.

Christine and the Queens – Tilted

Human Extinction And AI Denial

Erik Hoel at The Intrinsic Perspective:

While GPT-4 does have a radically different architecture from our own biological brains (like being solely feedforward and synchronous, whereas our own organic brains have a lot of feedback and asynchronous processing), AIs are neural networks inspired from biological ones. AIs have a learning rule that changes the strengths of the connections between their neurons, just like us—except their learning rule is applied from the outside by their engineers during a training phase, unlike us, who are forever learning (and forgetting). When artificial neural networks are trained, they often develop the properties we associate with real neural networks like grid-cells, shape-tuning, and visual illusions, which is why researchers in 2019 proposed a “deep learning framework for neuroscience.” There are even some prominent arguments that our own brains follow learning rules not too dissimilar. This similarity is why I advanced the Overfitted Brain Hypothesis, which argues that dreaming is a form of data augmentation, like a noise injection, that makes our nighttime experiences sparse and hallucinatory, and evolved to prevent overfitting.

While GPT-4 does have a radically different architecture from our own biological brains (like being solely feedforward and synchronous, whereas our own organic brains have a lot of feedback and asynchronous processing), AIs are neural networks inspired from biological ones. AIs have a learning rule that changes the strengths of the connections between their neurons, just like us—except their learning rule is applied from the outside by their engineers during a training phase, unlike us, who are forever learning (and forgetting). When artificial neural networks are trained, they often develop the properties we associate with real neural networks like grid-cells, shape-tuning, and visual illusions, which is why researchers in 2019 proposed a “deep learning framework for neuroscience.” There are even some prominent arguments that our own brains follow learning rules not too dissimilar. This similarity is why I advanced the Overfitted Brain Hypothesis, which argues that dreaming is a form of data augmentation, like a noise injection, that makes our nighttime experiences sparse and hallucinatory, and evolved to prevent overfitting.

more here.

Thursday Poem

Acadian Lane

Indigo against ocher, Atlantic

Blue abutting shore cliffs, bluffs, and sand,

All of the earth on Prince Edward Island

The red of dried blood, of weather-worn brick,

Of this rutted, twisting road leading down

Through the fishing village to the harbor

Where lobster boats rock, scarlet as lobster;

The bay’s depth, smoked glass, reflecting the town.

A few dogs rustle in the heat of the noon;

The gulls, the bitterns lift, circling again.

A man is walking his Acadian

Lane, the fine red dust rising off his clothes;

He begins to sing a slow French tune—

La mer, la terre, le monde est seulement ces choses!

by David St, John

from Strong Measures

Harper Collins, 1986