by Charlie Huenemann

“Thus the concept of a cause is nothing other than a synthesis (of that which follows in the temporal series with other appearances) in accordance with concepts; and without that sort of unity, which has its rule a priori, and which subjects the appearances to itself, thoroughgoing and universal, hence necessary unity of consciousness would not be encountered in the manifold perceptions. But these would then belong to no experience, and would consequently be without an object, and would be nothing but a blind play of representations, i.e., less than a dream.” (Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, p. 112(A))

“Thus the concept of a cause is nothing other than a synthesis (of that which follows in the temporal series with other appearances) in accordance with concepts; and without that sort of unity, which has its rule a priori, and which subjects the appearances to itself, thoroughgoing and universal, hence necessary unity of consciousness would not be encountered in the manifold perceptions. But these would then belong to no experience, and would consequently be without an object, and would be nothing but a blind play of representations, i.e., less than a dream.” (Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, p. 112(A))

[IN OTHER WORDS: Without concepts, experience is unthinkably weird.]

Back in the 17th century, some philosophers tried to place all knowers on a level playing field. John Locke claimed the human mind begins like a blank tablet, devoid of any characters, and it is experience, raw and unfiltered, that gives the mind something to think about. Since everybody has experience, this would mean everybody could develop knowledge of the world, and no one would be inherently better at it than anybody else.

It’s a valuable idea, and in the neighborhood of a great truth, but not very plausible as a model of how we manufacture knowledge. Later philosophers argued that, if this is how we do it, then we really don’t know much. For example, David Hume could not see how anyone could ever develop the idea of causality: you can watch the events in a workshop all the livelong day, and though you might see patterns in what happens, you will never see the necessity that is supposed to connect a cause with an effect. (Philosophers writing about this stuff have a hard time avoiding italics.)

But clearly we do end up with causal knowledge, as Hume himself never doubted, and we manage to navigate our ways through a steady world of enduring objects. We somehow end up with knowledge of an objective world. And we don’t remember that arriving at such knowledge was all that difficult. We just sort of grew into it, and now it seems so natural that it’s really hard to imagine not having it, and it’s even difficult not to find such knowledge perfectly obvious. But in fact it is anything but obvious (as Jochen Szangolies recently explored). Read more »

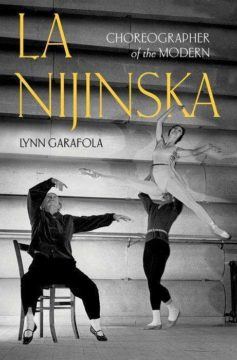

Bronislava Nijinska looked a lot like her brother, the famous dancer Vaslav Nijinsky. This proved an advantage to her own career, and a disadvantage. They’d grown up together, studied at the Imperial Ballet school in St. Petersburg, and begun their performing careers in the Maryinsky Theater. Both were trained in the virtuosic skills of the time. Acclaimed as a prodigy from the first, Vaslav left the home company soon after graduation to join Serge Diaghilev, founder of what became the legendary Ballets Russes. Vaslav’s story—his relationship with Diaghilev, his meteoric stardom in the early ballets of Michel Fokine, his budding choreographic career fostered by the possessive Diaghilev, his expulsion from the company following his marriage to Romola de Pulzsky, and his long mental deterioration—has been told many times. It’s only a sideline in Lynn Garafola’s new book La Nijinska: Choreographer of the Modern.

Bronislava Nijinska looked a lot like her brother, the famous dancer Vaslav Nijinsky. This proved an advantage to her own career, and a disadvantage. They’d grown up together, studied at the Imperial Ballet school in St. Petersburg, and begun their performing careers in the Maryinsky Theater. Both were trained in the virtuosic skills of the time. Acclaimed as a prodigy from the first, Vaslav left the home company soon after graduation to join Serge Diaghilev, founder of what became the legendary Ballets Russes. Vaslav’s story—his relationship with Diaghilev, his meteoric stardom in the early ballets of Michel Fokine, his budding choreographic career fostered by the possessive Diaghilev, his expulsion from the company following his marriage to Romola de Pulzsky, and his long mental deterioration—has been told many times. It’s only a sideline in Lynn Garafola’s new book La Nijinska: Choreographer of the Modern.

Wispy, thick, swirled and streaking, the dark lines burst outward, racing or splintering. The strongest impression one is left with while paging through this exquisitely produced volume of Kafka’s complete drawings is of minimally delineated figures in states of maximally dramatised unrest.

Wispy, thick, swirled and streaking, the dark lines burst outward, racing or splintering. The strongest impression one is left with while paging through this exquisitely produced volume of Kafka’s complete drawings is of minimally delineated figures in states of maximally dramatised unrest. Living as I do, mostly by choice, in a post-Babel cacophony of languages, I find I often discern meanings that are not really there. This is particularly easy to do in the contact zones of the former Angevin Empire, where more than a millennium’s worth of cross-hybridity between English and French has brought it about that this empire’s ruins are populated principally by faux amis, so that one must not so much learn new words, as reconceive words one already knows. Thus deception becomes disappointment, to assist is not to help but only to be present, to report is to postpone, to defend is to prohibit (sometimes), to verbalise is to fine, to sense is to smell, to mount is to get in, to descend is to get out, a location is a rental, ice-cream has a perfume instead of a flavor, and so on.

Living as I do, mostly by choice, in a post-Babel cacophony of languages, I find I often discern meanings that are not really there. This is particularly easy to do in the contact zones of the former Angevin Empire, where more than a millennium’s worth of cross-hybridity between English and French has brought it about that this empire’s ruins are populated principally by faux amis, so that one must not so much learn new words, as reconceive words one already knows. Thus deception becomes disappointment, to assist is not to help but only to be present, to report is to postpone, to defend is to prohibit (sometimes), to verbalise is to fine, to sense is to smell, to mount is to get in, to descend is to get out, a location is a rental, ice-cream has a perfume instead of a flavor, and so on. Every now and then engineers make an advance, and scientists and lay people begin to ponder the question of whether that advance might yield important insight into the human mind. Descartes wondered whether the mind might work on hydraulic principles; throughout the second half of the 20th century, many wondered whether the digital computer would offer a

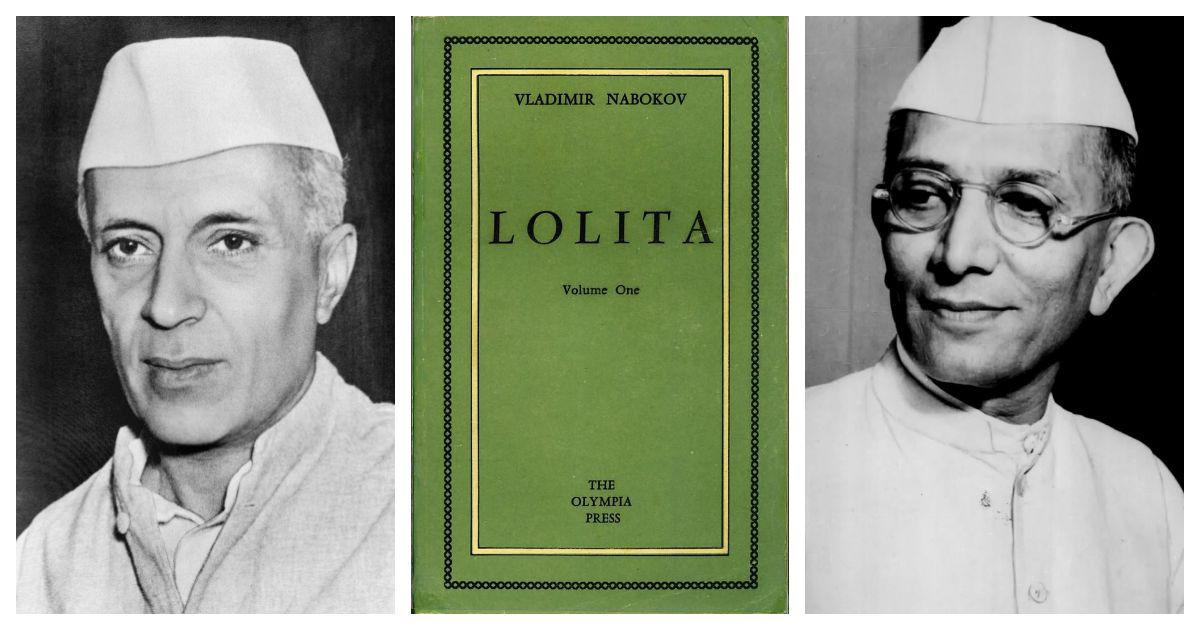

Every now and then engineers make an advance, and scientists and lay people begin to ponder the question of whether that advance might yield important insight into the human mind. Descartes wondered whether the mind might work on hydraulic principles; throughout the second half of the 20th century, many wondered whether the digital computer would offer a  In May 1959, DF Karaka, the founder editor of The Current, wrote a letter to then Finance Minister Moraji Desai about a book. Karaka explained that the book glorified a sexual relationship between a grown man and a teenage girl. He included a clipping from The Current that demanded an immediate ban on the “obscene” book.

In May 1959, DF Karaka, the founder editor of The Current, wrote a letter to then Finance Minister Moraji Desai about a book. Karaka explained that the book glorified a sexual relationship between a grown man and a teenage girl. He included a clipping from The Current that demanded an immediate ban on the “obscene” book. There’s always something relevant in clichés. If you think about it, every literary genre is a collection of clichés and commonplaces. It’s a system of expectations. The way events unfold in a fairy tale would be unacceptable in a noir novel or a science fiction story. Causal links are, to a great extent, predictable in each one of these genres. They are supposed to be predictable—even in their surprises. This is how we come to accept the reality of these worlds. And it’s so much fun to subvert those assumptions and clichés rather than to simply dismiss them, writing with one’s back turned to tradition. I should also say that these conventions usually have a heavy political load. Whenever something has calcified into a commonplace—as is the case with New York around the years of the boom and the crash—I think there is fascinating work to be done. Additionally, when I looked at the fossilized narratives from that period, I was surprised to find a void at their center: money. Even though, for obvious reasons, money is at the core of the American literature from that period, it remains a taboo—largely unquestioned and unexplored. I was unable to find many novels that talked about wealth and power in ways that were interesting to me. Class? Sure. Exploitation? Absolutely. Money? Not so much. And how bizarre is it that even though money has an almost transcendental quality in our culture it remains comparatively invisible in our literature?

There’s always something relevant in clichés. If you think about it, every literary genre is a collection of clichés and commonplaces. It’s a system of expectations. The way events unfold in a fairy tale would be unacceptable in a noir novel or a science fiction story. Causal links are, to a great extent, predictable in each one of these genres. They are supposed to be predictable—even in their surprises. This is how we come to accept the reality of these worlds. And it’s so much fun to subvert those assumptions and clichés rather than to simply dismiss them, writing with one’s back turned to tradition. I should also say that these conventions usually have a heavy political load. Whenever something has calcified into a commonplace—as is the case with New York around the years of the boom and the crash—I think there is fascinating work to be done. Additionally, when I looked at the fossilized narratives from that period, I was surprised to find a void at their center: money. Even though, for obvious reasons, money is at the core of the American literature from that period, it remains a taboo—largely unquestioned and unexplored. I was unable to find many novels that talked about wealth and power in ways that were interesting to me. Class? Sure. Exploitation? Absolutely. Money? Not so much. And how bizarre is it that even though money has an almost transcendental quality in our culture it remains comparatively invisible in our literature? In the parking areas, the drivers nestle their trucks in tightly packed rows. Their cabs function as kitchens, bedrooms, living rooms and offices. At night, drivers can be seen through their windshields — eating dinner or reclining in their bunks, bathed in the light of a Nintendo Switch or FaceTime call home.

In the parking areas, the drivers nestle their trucks in tightly packed rows. Their cabs function as kitchens, bedrooms, living rooms and offices. At night, drivers can be seen through their windshields — eating dinner or reclining in their bunks, bathed in the light of a Nintendo Switch or FaceTime call home. In March, Guy Reffitt, a supporter of the far-right militia group the Texas Three Percenters, became the first person convicted at trial for playing a role in the January 6, 2021,

In March, Guy Reffitt, a supporter of the far-right militia group the Texas Three Percenters, became the first person convicted at trial for playing a role in the January 6, 2021,  Francis Fukuyama is easily one of the most influential political thinkers of the last several decades.

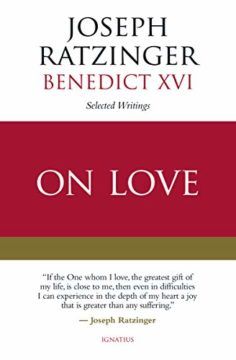

Francis Fukuyama is easily one of the most influential political thinkers of the last several decades. Nietzsche’s protest that one cannot cleave to a moral system originating in Christianity after denying the Christian God has implications far more profound than appear at first blush. Nietzsche could already see that purportedly secular doctrines in the ascendancy in his time, and which looked set to become orthodoxy – the sanctity and inherent dignity of human life, the fundamental equality of human lives – were in their origin and character inescapably Christian. It was an absurdity, he felt, that people should, at the moment of the “death of God”, cleave all the more fiercely to the doctrines which depended on Him; or to imagine that one could keep and could promote the gamut of Christian virtues – lovingkindness, humility, charity, counsels of gentleness or forgiveness – when the religious-metaphysical belief system underpinning them had been renounced. If one gives up the God, one ought also, or must also, for the sake of what Nietzsche called one’s intellectual conscience, give up the teachings of the religion. In this Nietzsche foresaw the coming orthodoxy of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries: secularised Christianity that calls itself by the names of humanism, egalitarianism, human rights, and which (quite unknowingly) preaches Christianity without Christ.

Nietzsche’s protest that one cannot cleave to a moral system originating in Christianity after denying the Christian God has implications far more profound than appear at first blush. Nietzsche could already see that purportedly secular doctrines in the ascendancy in his time, and which looked set to become orthodoxy – the sanctity and inherent dignity of human life, the fundamental equality of human lives – were in their origin and character inescapably Christian. It was an absurdity, he felt, that people should, at the moment of the “death of God”, cleave all the more fiercely to the doctrines which depended on Him; or to imagine that one could keep and could promote the gamut of Christian virtues – lovingkindness, humility, charity, counsels of gentleness or forgiveness – when the religious-metaphysical belief system underpinning them had been renounced. If one gives up the God, one ought also, or must also, for the sake of what Nietzsche called one’s intellectual conscience, give up the teachings of the religion. In this Nietzsche foresaw the coming orthodoxy of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries: secularised Christianity that calls itself by the names of humanism, egalitarianism, human rights, and which (quite unknowingly) preaches Christianity without Christ. “Thus the concept of a cause is nothing other than a synthesis (of that which follows in the temporal series with other appearances)

“Thus the concept of a cause is nothing other than a synthesis (of that which follows in the temporal series with other appearances)

I’m not a schoolteacher so I don’t know the exact routine that teachers have every morning before they leave their house, but I’m certain it shouldn’t involve checking the magazine of a 9mm Glock and perhaps even chambering a round before their commute to school. I have known several teachers and in general, they are idealistic, hard-working, and underpaid. The challenges of teaching 30 hyper 10-year-olds how to write a clear sentence or conquer fractions has to be consuming enough without also having a counter-assault plan in the back of your mind.

I’m not a schoolteacher so I don’t know the exact routine that teachers have every morning before they leave their house, but I’m certain it shouldn’t involve checking the magazine of a 9mm Glock and perhaps even chambering a round before their commute to school. I have known several teachers and in general, they are idealistic, hard-working, and underpaid. The challenges of teaching 30 hyper 10-year-olds how to write a clear sentence or conquer fractions has to be consuming enough without also having a counter-assault plan in the back of your mind.