by Carol A Westbrook

Summer is finally here, and nothing says “summer” more than biting into a sweet, ripe freshly-picked tomato, still warm from the sun, eaten with a pinch of salt. The variety of tomatoes is incredible; from sweet 1-pound beefsteaks, delicious eaten raw, to plum tomatoes for canning and sauces, to colorful cheery cherry tomatoes, adding a spot of color to salads and crudities.

Even green tomatoes, stubbornly refusing to ripen at the end of the season, have a use in salsa, or simply or breaded and fried.

The best way to a sweet tomato is to grow your own. I have fond memories of my father’s garden patch in our Chicago yard, where he tended about a dozen tomato plants of several varieties. On warm days in late August I’d walk through the garden with a saltshaker, pick a perfectly ripe tomato, shake on some salt, and dig in, sweet warm tomato juice dripping down my chin. We four kids pitched in, tilling the soil, setting out the plants, weeding, and keeping an eye out for those plump, ugly, disgusting caterpillars, that could devour an entire tomato vine in a matter of hours! Read more »

Even though I have attended most of the meetings of the September group over the last 40 years, my own participation in the group has really been more like that of an interested outsider looking in. This is for mainly two reasons. One is that my research primarily being on developing countries, it had very little overlap with research areas of almost everybody else in the group. I often hesitated presenting my research because I thought the specialized details of my work might bore the rest of the members, even though I knew they’d politely listen to me. So I often participated more actively in the session in each meeting reserved for some topical global issue for general discussion rather than for presentation of original research.

Even though I have attended most of the meetings of the September group over the last 40 years, my own participation in the group has really been more like that of an interested outsider looking in. This is for mainly two reasons. One is that my research primarily being on developing countries, it had very little overlap with research areas of almost everybody else in the group. I often hesitated presenting my research because I thought the specialized details of my work might bore the rest of the members, even though I knew they’d politely listen to me. So I often participated more actively in the session in each meeting reserved for some topical global issue for general discussion rather than for presentation of original research. Artworks are not to be experienced but to be understood: From all directions, across the visual art world’s many arenas, the relationship between art and the viewer has come to be framed in this way. An artwork communicates a message, and comprehending that message is the work of its audience. Paintings are their images; physically encountering an original is nice, yes, but it’s not as if any essence resides there. Even a verbal description of a painting provides enough information for its message to be clear.

Artworks are not to be experienced but to be understood: From all directions, across the visual art world’s many arenas, the relationship between art and the viewer has come to be framed in this way. An artwork communicates a message, and comprehending that message is the work of its audience. Paintings are their images; physically encountering an original is nice, yes, but it’s not as if any essence resides there. Even a verbal description of a painting provides enough information for its message to be clear. Every so often stories of

Every so often stories of  Robert P. George: The current situation is one in which people in general—including people on college campuses, not only students, but faculty, not only untenured (and therefore, in a certain sense, insecure) faculty, but tenured faculty who are secure—are censoring themselves. All the studies that have been done on this subject reveal that people are not saying what they truly believe, or not raising certain questions they’d like to ask, because they fear the social or professional consequences of “saying the wrong thing,” or saying the right thing in “the wrong” way. Well, this, in my opinion, is terrible for institutions of higher learning, colleges and universities. It makes it impossible for us to prosecute our fundamental mission, the mission of pursuing knowledge of truth, but it’s also terrible for a democratic republic.

Robert P. George: The current situation is one in which people in general—including people on college campuses, not only students, but faculty, not only untenured (and therefore, in a certain sense, insecure) faculty, but tenured faculty who are secure—are censoring themselves. All the studies that have been done on this subject reveal that people are not saying what they truly believe, or not raising certain questions they’d like to ask, because they fear the social or professional consequences of “saying the wrong thing,” or saying the right thing in “the wrong” way. Well, this, in my opinion, is terrible for institutions of higher learning, colleges and universities. It makes it impossible for us to prosecute our fundamental mission, the mission of pursuing knowledge of truth, but it’s also terrible for a democratic republic.

I

I In an interview with the Guardian, filmmaker John Waters — creator of cult classics “Pink Flamingoes” and “Female Trouble” — lamented the rise of

In an interview with the Guardian, filmmaker John Waters — creator of cult classics “Pink Flamingoes” and “Female Trouble” — lamented the rise of  Liza Featherstone in The New Republic:

Liza Featherstone in The New Republic: Colin Burrow on Stanley Cavell’s Here and There in the LRB:

Colin Burrow on Stanley Cavell’s Here and There in the LRB: Nina Eichacker in Phenomenal World:

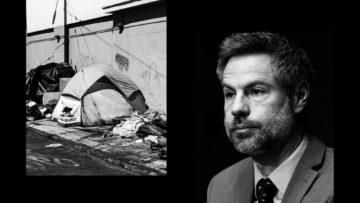

Nina Eichacker in Phenomenal World: SAN FRANCISCO—Michael Shellenberger was more excited to tour the Tenderloin than I was, even though it was my idea. I was nervous about provoking desperate people in various states of disrepair. Shellenberger, meanwhile, seemed intent on showing that many homeless people are addicted to drugs. (If that seems callous to you, Shellenberger would say you’re in thrall to liberal “victim ideology.”) He told me not to worry. “You seem like a tough Russian chick, right?” he said as we walked up narrow sidewalks where

SAN FRANCISCO—Michael Shellenberger was more excited to tour the Tenderloin than I was, even though it was my idea. I was nervous about provoking desperate people in various states of disrepair. Shellenberger, meanwhile, seemed intent on showing that many homeless people are addicted to drugs. (If that seems callous to you, Shellenberger would say you’re in thrall to liberal “victim ideology.”) He told me not to worry. “You seem like a tough Russian chick, right?” he said as we walked up narrow sidewalks where  Ira Glass worked through and missed our scheduled Zoom interview. “It’s really just been like a normal work week, but I just didn’t manage it as ideally as I could have,” he told me, apologetically, when we chat a few days later. He missed the call because that week’s episode of This American Life, the podcast and radio show he founded in 1995 and still hosts today, had to be completely re-edited and recorded. “Stuff just has to get done… it gets very complicated.”

Ira Glass worked through and missed our scheduled Zoom interview. “It’s really just been like a normal work week, but I just didn’t manage it as ideally as I could have,” he told me, apologetically, when we chat a few days later. He missed the call because that week’s episode of This American Life, the podcast and radio show he founded in 1995 and still hosts today, had to be completely re-edited and recorded. “Stuff just has to get done… it gets very complicated.” I was reading the kinds of essays, in German, that academics write about the kinds of things that Peter is obsessed with. But my big reading event of that period was the diaries of Victor Klemperer—one of the great reading experiences of my life. It’s like if Proust were not about venal parties. It’s nonfiction, and takes place from 1933 to 1945 in Germany, from the point of view of a middle-age Jewish intellectual who survived it all out in the open, because he had a so-called Aryan wife who stood by him. He lived without having to go to a camp. And it’s so incredibly moving, because it’s a diary, so as he’s writing it, he doesn’t know what’s going to happen. There are constant bits like, Hitler’s going to get voted out. He’s going to lose the war. Everybody secretly hates him, nobody takes this guy seriously. The Americans will be here next week. It’s the most magnificent book.

I was reading the kinds of essays, in German, that academics write about the kinds of things that Peter is obsessed with. But my big reading event of that period was the diaries of Victor Klemperer—one of the great reading experiences of my life. It’s like if Proust were not about venal parties. It’s nonfiction, and takes place from 1933 to 1945 in Germany, from the point of view of a middle-age Jewish intellectual who survived it all out in the open, because he had a so-called Aryan wife who stood by him. He lived without having to go to a camp. And it’s so incredibly moving, because it’s a diary, so as he’s writing it, he doesn’t know what’s going to happen. There are constant bits like, Hitler’s going to get voted out. He’s going to lose the war. Everybody secretly hates him, nobody takes this guy seriously. The Americans will be here next week. It’s the most magnificent book.