Robin McKie at The Guardian:

Once hailed as a source of electricity that would be too cheap to meter, atomic power has come a long way since the 1950s – mostly downhill. Far from being cost-free, nuclear-generated electricity is today more expensive than power produced by coal, gas, wind or solar plants while sites storing spent uranium and irradiated equipment litter the globe, a deadly radioactive legacy that will endure for hundreds of thousands of years. For good measure, most analysts now accept that the spread of atomic energy played a crucial role in driving nuclear weapon proliferation.

Once hailed as a source of electricity that would be too cheap to meter, atomic power has come a long way since the 1950s – mostly downhill. Far from being cost-free, nuclear-generated electricity is today more expensive than power produced by coal, gas, wind or solar plants while sites storing spent uranium and irradiated equipment litter the globe, a deadly radioactive legacy that will endure for hundreds of thousands of years. For good measure, most analysts now accept that the spread of atomic energy played a crucial role in driving nuclear weapon proliferation.

Then there are the disasters. Some of the world’s worst accidents have had nuclear origins and half a dozen especially egregious examples have been selected by Harvard historian Serhii Plokhy to support his thesis that atomic power is never going to be the energy saviour of our imperilled species.

more here.

W

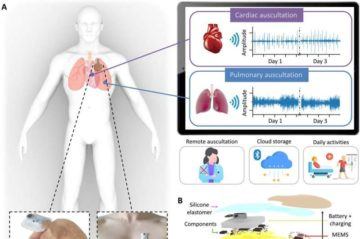

W Digital stethoscopes provide better results compared to conventional methods to record and visualize modern

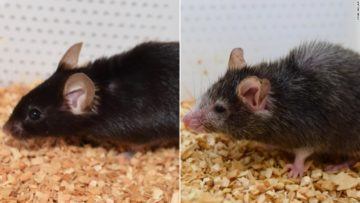

Digital stethoscopes provide better results compared to conventional methods to record and visualize modern  In molecular biologist David Sinclair’s

In molecular biologist David Sinclair’s

W

W Perhaps the most Melvillean chapter of The Sea Around Us is “Wind and Water,” which goes into fascinating detail about how winds (and volcanoes) create waves (and tsunamis), how many thousands of miles they travel, how each one is measured (five hundred miles of fetch!), and what destruction the largest of them can cause, especially when they come ashore “armed with stones and rock fragments.” Maritime history is replete with legends of gigantic waves, many of which can sound apocryphal, but Carson’s information about waves in excess of 60 feet is relentlessly persuasive. To cite only one of these, she tells of a huge wave that lifted a 135-pound rock and “hurled [it] high above the lightkeeper’s house on Tillamook Rock [in Oregon] . . . 100 feet above sea level,” smashing it to pieces. She also quotes Lord Bryce’s observation about storm surf on the coast of Tierra del Fuego, “There is not in the world a coast more terrible than this!” Charles Darwin agreed, not mincing his words: “The sight of such a coast is enough to make a landsman dream for a week about death, peril, and shipwreck.”

Perhaps the most Melvillean chapter of The Sea Around Us is “Wind and Water,” which goes into fascinating detail about how winds (and volcanoes) create waves (and tsunamis), how many thousands of miles they travel, how each one is measured (five hundred miles of fetch!), and what destruction the largest of them can cause, especially when they come ashore “armed with stones and rock fragments.” Maritime history is replete with legends of gigantic waves, many of which can sound apocryphal, but Carson’s information about waves in excess of 60 feet is relentlessly persuasive. To cite only one of these, she tells of a huge wave that lifted a 135-pound rock and “hurled [it] high above the lightkeeper’s house on Tillamook Rock [in Oregon] . . . 100 feet above sea level,” smashing it to pieces. She also quotes Lord Bryce’s observation about storm surf on the coast of Tierra del Fuego, “There is not in the world a coast more terrible than this!” Charles Darwin agreed, not mincing his words: “The sight of such a coast is enough to make a landsman dream for a week about death, peril, and shipwreck.” While it is fashionable for some female academics, journalists and social commentators to declare the

While it is fashionable for some female academics, journalists and social commentators to declare the  When the

When the This paper links two things that are often dealt with separately when discussing what we mean by the word “just” in the notion of a “just transition”. On the one hand, activists and reformers – especially those promoting the United States (US) version of the Green New Deal (GND) – see this as an opportunity to empower marginalised populations and redistribute wealth-generating assets using the state in the form of green industrial policy. On the other hand lies private finance, especially in the form of asset managers, who own huge swathes of global companies. Their investment decisions are critical to the transition, but they have no intention of allowing such a redistribution of assets and power. Indeed, they see the function of the state as using its balance sheet to insure private investors against losses. We use these competing notions of “just” as a way to discuss how we can have a transition that leverages the investments of the private sector without once again simply giving capital everything it wants at the expense of everyone else.

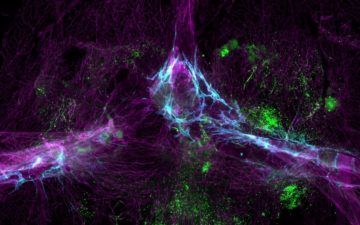

This paper links two things that are often dealt with separately when discussing what we mean by the word “just” in the notion of a “just transition”. On the one hand, activists and reformers – especially those promoting the United States (US) version of the Green New Deal (GND) – see this as an opportunity to empower marginalised populations and redistribute wealth-generating assets using the state in the form of green industrial policy. On the other hand lies private finance, especially in the form of asset managers, who own huge swathes of global companies. Their investment decisions are critical to the transition, but they have no intention of allowing such a redistribution of assets and power. Indeed, they see the function of the state as using its balance sheet to insure private investors against losses. We use these competing notions of “just” as a way to discuss how we can have a transition that leverages the investments of the private sector without once again simply giving capital everything it wants at the expense of everyone else. The brain is the body’s sovereign, and receives protection in keeping with its high status. Its cells are long-lived and shelter inside a fearsome fortification called the blood–brain barrier. For a long time, scientists thought that the brain was completely cut off from the chaos of the rest of the body — especially its eager defence system, a mass of immune cells that battle infections and whose actions could threaten a ruler caught in the crossfire. In the past decade, however, scientists have discovered that the job of protecting the brain isn’t as straightforward as they thought. They’ve learnt that its fortifications have gateways and gaps, and that its borders are bustling with active immune cells.

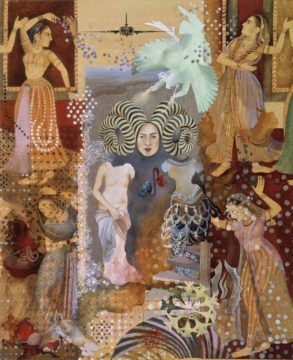

The brain is the body’s sovereign, and receives protection in keeping with its high status. Its cells are long-lived and shelter inside a fearsome fortification called the blood–brain barrier. For a long time, scientists thought that the brain was completely cut off from the chaos of the rest of the body — especially its eager defence system, a mass of immune cells that battle infections and whose actions could threaten a ruler caught in the crossfire. In the past decade, however, scientists have discovered that the job of protecting the brain isn’t as straightforward as they thought. They’ve learnt that its fortifications have gateways and gaps, and that its borders are bustling with active immune cells. In 2019, two Persian paintings sold in a private-auction house, in London, for roughly eight hundred thousand pounds each. The paintings were illuminated manuscripts, or “miniature” paintings, and they belonged to the same book: a fifteenth-century edition of the Nahj al-Faradis, which narrates Muhammad’s journey through the layers of heaven and hell. The original book, once an artistic masterpiece, had been ripped apart, reduced to sixty lavish images. Bound, the manuscript was likely worth a few million pounds; dismembered, its contents have sold for more than fifty million.

In 2019, two Persian paintings sold in a private-auction house, in London, for roughly eight hundred thousand pounds each. The paintings were illuminated manuscripts, or “miniature” paintings, and they belonged to the same book: a fifteenth-century edition of the Nahj al-Faradis, which narrates Muhammad’s journey through the layers of heaven and hell. The original book, once an artistic masterpiece, had been ripped apart, reduced to sixty lavish images. Bound, the manuscript was likely worth a few million pounds; dismembered, its contents have sold for more than fifty million. “I’m stricken by the ricochet wonder of it all,” poet Diane Ackerman wrote in her sublime

“I’m stricken by the ricochet wonder of it all,” poet Diane Ackerman wrote in her sublime  What I take from this is not so much that Power is a radical but rather that he believes style is not a substitute for ideas, nor should it be used as an evasive measure to obscure areas of darkness or deployed as a bully in debate. His own clear prose works hard at allowing him to do some expansive thinking in what is still a concise amount of space. In the longer essays various big ideas (example: the Apocalypse) are explored in some depth with a lot of ground crisply covered in relatively few pages.

What I take from this is not so much that Power is a radical but rather that he believes style is not a substitute for ideas, nor should it be used as an evasive measure to obscure areas of darkness or deployed as a bully in debate. His own clear prose works hard at allowing him to do some expansive thinking in what is still a concise amount of space. In the longer essays various big ideas (example: the Apocalypse) are explored in some depth with a lot of ground crisply covered in relatively few pages.