Steven Poole in The Guardian:

Like most big-idea books, this one begins by absurdly overstating the novelty of its argument. The author promises to reveal “a radical idea” that has been “erased from the annals of world history”. It is, even, “a new view of humankind”. Some measure of bathos is presumably intended when we learn that this radical new view is that “most people, deep down, are pretty decent”. But there appears to be no authorial shame over the laughably bogus claim that this idea has been “erased” from history, presumably by a dark centuries-long conspiracy of secretive misanthropes, to some bafflingly obscure end. Not yet erased from the annals of history, for example, is the 18th-century philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, on whom the author regularly calls for his view that humans are naturally nice, and it is the institutions of civilisation that have corrupted us. Bregman contrasts this with what he calls, following the biologist Frans de Waal, “veneer theory”: the view (attributed to Hobbes among others) that civilisation is a thin skin of decency barely concealing the savage ape underneath.

Like most big-idea books, this one begins by absurdly overstating the novelty of its argument. The author promises to reveal “a radical idea” that has been “erased from the annals of world history”. It is, even, “a new view of humankind”. Some measure of bathos is presumably intended when we learn that this radical new view is that “most people, deep down, are pretty decent”. But there appears to be no authorial shame over the laughably bogus claim that this idea has been “erased” from history, presumably by a dark centuries-long conspiracy of secretive misanthropes, to some bafflingly obscure end. Not yet erased from the annals of history, for example, is the 18th-century philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, on whom the author regularly calls for his view that humans are naturally nice, and it is the institutions of civilisation that have corrupted us. Bregman contrasts this with what he calls, following the biologist Frans de Waal, “veneer theory”: the view (attributed to Hobbes among others) that civilisation is a thin skin of decency barely concealing the savage ape underneath.

You might suspect that there is something to both these views simultaneously, but Humankind is a polemic in the high Gladwellian style and so aims to be a simple lesson overturning our allegedly preconceived ideas, with the help of carefully selected study citations and pseudo-novelistic scenes from the blitz and other teachable stories. The “veneer” theory, Bregman insists, is totally wrong. What is his evidence? Infants and toddlers, studies suggest, have an innate bias towards fairness and cooperation. When some Tongan children were shipwrecked on a Pacific island for over a year, they cooperated generously rather than re-enacting Lord of the Flies. In the first world war, German and British soldiers played football on Christmas Day. (Rather courageously, the author chooses this overfamiliar fable as his sentimental endpiece.)

More here.

Thousands of academics and major scientific organizations worldwide will stop work on 10 June as part of a global stand against anti-Black racism in science. More than 4,000 scientists as well as societies, universities and publishers, will join a call to “Strike for Black Lives,” halting their usual work activities to learn about systemic racism in the research community and to craft ways to address inequalities. The event is being planned by two ad hoc groups of scientists using hashtags such as

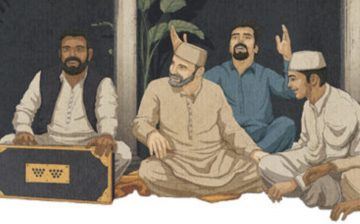

Thousands of academics and major scientific organizations worldwide will stop work on 10 June as part of a global stand against anti-Black racism in science. More than 4,000 scientists as well as societies, universities and publishers, will join a call to “Strike for Black Lives,” halting their usual work activities to learn about systemic racism in the research community and to craft ways to address inequalities. The event is being planned by two ad hoc groups of scientists using hashtags such as  After barreling through the relentlessly flat, verdant Punjabi hinterland in a rented Toyota, stopping briefly for naan, kebabs, and petrol, we hit town at three, four in the morning, and at three, four in the morning, music wafts through the still, sticky summer air. Millions gather each year for ten days in the hilly medieval town of Pakpattan, in Pakistan, to commemorate the death anniversary of the twelfth-century saint Baba Farid, celebrating the reunion of man and his maker with qawwali—call it Muslim soul. When Doc, a pal and Pakpattan regular, urged me to join him on the pilgrimage the night before—it’s Baba’s 776th death anniversary, he informs me—I decided to accompany him. I can’t refuse Doc: I’ve got his back; he’s got mine. And who knows? Perhaps Baba will bless me as well. But you have to believe to be blessed.

After barreling through the relentlessly flat, verdant Punjabi hinterland in a rented Toyota, stopping briefly for naan, kebabs, and petrol, we hit town at three, four in the morning, and at three, four in the morning, music wafts through the still, sticky summer air. Millions gather each year for ten days in the hilly medieval town of Pakpattan, in Pakistan, to commemorate the death anniversary of the twelfth-century saint Baba Farid, celebrating the reunion of man and his maker with qawwali—call it Muslim soul. When Doc, a pal and Pakpattan regular, urged me to join him on the pilgrimage the night before—it’s Baba’s 776th death anniversary, he informs me—I decided to accompany him. I can’t refuse Doc: I’ve got his back; he’s got mine. And who knows? Perhaps Baba will bless me as well. But you have to believe to be blessed. When protests erupted in the US in response to the killing of George Floyd on May 25, the anger over police brutality was also fuelled by a sense of simmering injustice over the impact of coronavirus. Not only have black people died from the disease in disproportionately high numbers: there are early signs they will bear the brunt of the economic fallout too.

When protests erupted in the US in response to the killing of George Floyd on May 25, the anger over police brutality was also fuelled by a sense of simmering injustice over the impact of coronavirus. Not only have black people died from the disease in disproportionately high numbers: there are early signs they will bear the brunt of the economic fallout too. A podcast only hits the century mark once! And for Mindscape, this is it. There have been holiday messages and bonus episodes and the like. But this is the 100th officially-numbered episode. To celebrate, I decided to treat myself to a solo episode in which I reflect, somewhat non-systematically, on the age-old question of the meaning of life. I end up spending a lot (most?) of the time talking about the meaning of “life,” i.e. what it means to be a living organism in a naturalistic universe. But then I go on to muse about the construction of human meaning in a world where values are not imposed on us or objectively grounded in physical facts.

A podcast only hits the century mark once! And for Mindscape, this is it. There have been holiday messages and bonus episodes and the like. But this is the 100th officially-numbered episode. To celebrate, I decided to treat myself to a solo episode in which I reflect, somewhat non-systematically, on the age-old question of the meaning of life. I end up spending a lot (most?) of the time talking about the meaning of “life,” i.e. what it means to be a living organism in a naturalistic universe. But then I go on to muse about the construction of human meaning in a world where values are not imposed on us or objectively grounded in physical facts. Less than two weeks after Floyd’s killing, the American death toll from the novel coronavirus has surpassed 100,000. Rates of infection,

Less than two weeks after Floyd’s killing, the American death toll from the novel coronavirus has surpassed 100,000. Rates of infection,  We moved forward with the idea of assembling a canon, aware of the chutzpah, based on a few understandings. One is our belief that even when canon formation is not taking place explicitly in a closed gathering, certain ideas and texts become implicitlycanonical through other means such as compelling presentation, citation, and education. Communities and consensuses can create canon by bringing powerful ideas to life and to market, and by privileging some ideas and texts over others. For example, Yosef H. Yerushalmi’s Zakhor is required reading in dozens of college and graduate school courses in Jewish Studies; it is among the most commonly cited texts in Jewish Studies lectures in both academic and lay settings. No one person decided that the book is important, but the book has emerged over time as a canonical piece of Jewish Studies scholarship with relevance for the larger Jewish community. In engaging actively and directly in canon formation, in naming what we were doing an act of “canonization,” and in inviting commentary from our colleagues we hoped to call attention to the implicit canonization that was already happening and to open a conversation about it.

We moved forward with the idea of assembling a canon, aware of the chutzpah, based on a few understandings. One is our belief that even when canon formation is not taking place explicitly in a closed gathering, certain ideas and texts become implicitlycanonical through other means such as compelling presentation, citation, and education. Communities and consensuses can create canon by bringing powerful ideas to life and to market, and by privileging some ideas and texts over others. For example, Yosef H. Yerushalmi’s Zakhor is required reading in dozens of college and graduate school courses in Jewish Studies; it is among the most commonly cited texts in Jewish Studies lectures in both academic and lay settings. No one person decided that the book is important, but the book has emerged over time as a canonical piece of Jewish Studies scholarship with relevance for the larger Jewish community. In engaging actively and directly in canon formation, in naming what we were doing an act of “canonization,” and in inviting commentary from our colleagues we hoped to call attention to the implicit canonization that was already happening and to open a conversation about it. 100,000 square metres of fabric was used to wrap the Reichstag in 1995. Christo and Jeanne-Claude said at the time that the project was born out of his ‘acute interest’ as a political refugee in the relationship between East and West: ‘Here they meet in the most dramatic way.’ The event received wide press coverage, like all their projects, but was also the subject of a personal documentary about Christo and Anani. Standing beside the wrapped Reichstag, leaning against the remains of the Berlin Wall, Anani, by then a famous actor, is anguished: ‘I never had Hristo’s energy. He left with a pencil in his pocket and made it. I never dared.’

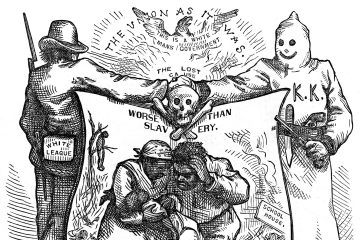

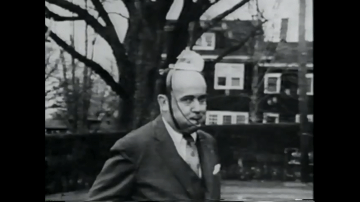

100,000 square metres of fabric was used to wrap the Reichstag in 1995. Christo and Jeanne-Claude said at the time that the project was born out of his ‘acute interest’ as a political refugee in the relationship between East and West: ‘Here they meet in the most dramatic way.’ The event received wide press coverage, like all their projects, but was also the subject of a personal documentary about Christo and Anani. Standing beside the wrapped Reichstag, leaning against the remains of the Berlin Wall, Anani, by then a famous actor, is anguished: ‘I never had Hristo’s energy. He left with a pencil in his pocket and made it. I never dared.’ There is an unholy invocation that rises from some Americans in times of racial distress. It is an exclamation from the voices of the status quo, the clarion call of conservative thinking: What would Martin Luther King do? It is as unauthentic and uninspiring as it is ambiguous – and that is the point. Reducing Dr. King’s understanding of racial and social issues to a warped perspective of the “I Have A Dream” speech is propagandist and ahistorical, but it has worked.

There is an unholy invocation that rises from some Americans in times of racial distress. It is an exclamation from the voices of the status quo, the clarion call of conservative thinking: What would Martin Luther King do? It is as unauthentic and uninspiring as it is ambiguous – and that is the point. Reducing Dr. King’s understanding of racial and social issues to a warped perspective of the “I Have A Dream” speech is propagandist and ahistorical, but it has worked. The first thing

The first thing  In coping with the dire economic crisis in the wake of the pandemic many developing countries have resorted to cash assistance to the poor for immediate relief. Beyond the relief aspect, many macro-economists have also pointed to the need for such programs to boost mass consumer demand in a period of one of the deepest slumps of general economic activity in many decades. As I have been an advocate for universal basic income (UBI) in poor countries for more than a decade now—my first published paper on the subject came out in India in March 2011 in the Economic and Political Weekly— I have often been asked if the widespread adoption of such cash assistance programs indicates that it is now a propitious time for UBI. While I have supported the cash relief programs in the context of the crisis (most of these programs have not been universal, mainly targeted to the poor) and consider the experience gained in this as generally useful, I think those who like me have supported UBI have usually thought about it in a longer-time framework and in the context of a more ‘normal’ state of the economy with appropriate institutions, political support base, and administrative structures in place. Of course, I’ll not object if in a post-pandemic world attempts are made to help the temporary crisis programs ultimately extend or evolve into a more general UBI program in poor countries.

In coping with the dire economic crisis in the wake of the pandemic many developing countries have resorted to cash assistance to the poor for immediate relief. Beyond the relief aspect, many macro-economists have also pointed to the need for such programs to boost mass consumer demand in a period of one of the deepest slumps of general economic activity in many decades. As I have been an advocate for universal basic income (UBI) in poor countries for more than a decade now—my first published paper on the subject came out in India in March 2011 in the Economic and Political Weekly— I have often been asked if the widespread adoption of such cash assistance programs indicates that it is now a propitious time for UBI. While I have supported the cash relief programs in the context of the crisis (most of these programs have not been universal, mainly targeted to the poor) and consider the experience gained in this as generally useful, I think those who like me have supported UBI have usually thought about it in a longer-time framework and in the context of a more ‘normal’ state of the economy with appropriate institutions, political support base, and administrative structures in place. Of course, I’ll not object if in a post-pandemic world attempts are made to help the temporary crisis programs ultimately extend or evolve into a more general UBI program in poor countries. What does it mean to be white in America in 2020?

What does it mean to be white in America in 2020?

May 26, 2020

May 26, 2020

Have a look at the

Have a look at the