Vanessa A. Bee in In These Times:

Anthony Fauci, who leads the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, believes a vaccine is unlikely to arrive within a year. Others in the field suggest even 18 months is optimistic, and that’s assuming it can be quickly mass produced and nothing goes wrong. As Bill Ackman, the billionaire and founder of investment firm Pershing Square, warns on CNBC, “Capitalism does not work in an 18-month shutdown.”

Anthony Fauci, who leads the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, believes a vaccine is unlikely to arrive within a year. Others in the field suggest even 18 months is optimistic, and that’s assuming it can be quickly mass produced and nothing goes wrong. As Bill Ackman, the billionaire and founder of investment firm Pershing Square, warns on CNBC, “Capitalism does not work in an 18-month shutdown.”

So how did the United States, dubbed “the greatest engine of innovation that has ever existed” by New York Times pundit Thomas L. Friedman, end up so sorely unprepared?

Perhaps one clue lies in Texas, where a potentially effective vaccine has been stalled since 2016. Dr. Peter Jay Hotez and his team at Texas Children’s Hospital Center for Vaccine Development created a potential vaccine for one deadly strain of coronavirus four years ago—which Hotez believes could be effective against the strain we face now—but the project stalled after the team struggled to secure funding for human trials. Even the looming crisis did not guarantee additional money.

More here. [Thanks to Daniel Jimenez Avarez.]

The soul exists. That’s what it does. It doesn’t need traditional religion or occultist speculation to justify, let alone explain, its existence. The soul can simply be a thing-in-itself, free from purpose or the need to be redeemed or maintained or isolated for study. We often talk about the soul simply as the nonmaterial and thus mysterious aspect of our being, something we feel but can’t point to—or what is silent and constant, enclosed in our mortal coil. It’s also entirely possible that there’s no nonmaterial part of our being, and whatever intangible dimension of ourselves we feel or think we feel is just, as yet, unexplained by science. Or maybe we do have souls, but they die with the body. Given such speculative uncertainty, the closest approach to the soul for many without recourse to religious reassurance is “consciousness,” though this may amount to no more than replacing one word with another.

The soul exists. That’s what it does. It doesn’t need traditional religion or occultist speculation to justify, let alone explain, its existence. The soul can simply be a thing-in-itself, free from purpose or the need to be redeemed or maintained or isolated for study. We often talk about the soul simply as the nonmaterial and thus mysterious aspect of our being, something we feel but can’t point to—or what is silent and constant, enclosed in our mortal coil. It’s also entirely possible that there’s no nonmaterial part of our being, and whatever intangible dimension of ourselves we feel or think we feel is just, as yet, unexplained by science. Or maybe we do have souls, but they die with the body. Given such speculative uncertainty, the closest approach to the soul for many without recourse to religious reassurance is “consciousness,” though this may amount to no more than replacing one word with another. Though Almond doesn’t outright say it, God: A New Biography implies that the various Reformation theologies emerging in early modernity were responsible not just for separating God from rational philosophical approximation, but for a certain anemic flattening of our language concerning the divine as well. What is thus born is the “God” whom most of us think of when we hear that word; not the cloud of unknowing of apophatic mystics or the “Ground of Being” of post-modern theologians, but the white-haired “Nobodaddy” dismissed by William Blake. Such a God has little to do with conceptions of ultimate meaning, and is rather a projected dictatorial figure, not the domain of ultimate significance to be discussed, but rather an idol to be dismissed. Rejected, for that matter, by the forward-thinking peasants of Soira and dismissed by many today (including myself). It would be a mistake to read that as necessarily an atheism. Speaking for myself, what I reject is that limited definition of God, rather than the discourse toward ultimate meaning which Almond so capably describes over the course of his book.

Though Almond doesn’t outright say it, God: A New Biography implies that the various Reformation theologies emerging in early modernity were responsible not just for separating God from rational philosophical approximation, but for a certain anemic flattening of our language concerning the divine as well. What is thus born is the “God” whom most of us think of when we hear that word; not the cloud of unknowing of apophatic mystics or the “Ground of Being” of post-modern theologians, but the white-haired “Nobodaddy” dismissed by William Blake. Such a God has little to do with conceptions of ultimate meaning, and is rather a projected dictatorial figure, not the domain of ultimate significance to be discussed, but rather an idol to be dismissed. Rejected, for that matter, by the forward-thinking peasants of Soira and dismissed by many today (including myself). It would be a mistake to read that as necessarily an atheism. Speaking for myself, what I reject is that limited definition of God, rather than the discourse toward ultimate meaning which Almond so capably describes over the course of his book. Welcome to Cowardly Police News!” booms Zung Jung-ngai. Dressed in a crisp white shirt, black tie and bin bags that cover his neck and hands, Zung beams at his audience of prospective recruits to the Hong Kong Police Force. Want a job that guarantees good health? Where you can get “protective biohazard suits’’ quicker than front-line medics fighting coronavirus? Where you can obtain AR-15s, water cannons and gas masks? Zung looks into the camera: all you need to do, he says, is join the police.

Welcome to Cowardly Police News!” booms Zung Jung-ngai. Dressed in a crisp white shirt, black tie and bin bags that cover his neck and hands, Zung beams at his audience of prospective recruits to the Hong Kong Police Force. Want a job that guarantees good health? Where you can get “protective biohazard suits’’ quicker than front-line medics fighting coronavirus? Where you can obtain AR-15s, water cannons and gas masks? Zung looks into the camera: all you need to do, he says, is join the police. James Mattis, the esteemed Marine general who resigned as secretary of defense in December 2018 to protest Donald Trump’s Syria policy, has, ever since, kept studiously silent about Trump’s performance as president. But he has now broken his silence, writing an extraordinary broadside in which he denounces the president for dividing the nation, and accuses him of ordering the U.S. military to violate the constitutional rights of American citizens. “I have watched this week’s unfolding events, angry and appalled,” Mattis writes. “The words ‘Equal Justice Under Law’ are carved in the pediment of the United States Supreme Court. This is precisely what protesters are rightly demanding. It is a wholesome and unifying demand—one that all of us should be able to get behind. We must not be distracted by a small number of lawbreakers. The protests are defined by tens of thousands of people of conscience who are insisting that we live up to our values—our values as people and our values as a nation.” He goes on, “We must reject and hold accountable those in office who would make a mockery of our Constitution.”

James Mattis, the esteemed Marine general who resigned as secretary of defense in December 2018 to protest Donald Trump’s Syria policy, has, ever since, kept studiously silent about Trump’s performance as president. But he has now broken his silence, writing an extraordinary broadside in which he denounces the president for dividing the nation, and accuses him of ordering the U.S. military to violate the constitutional rights of American citizens. “I have watched this week’s unfolding events, angry and appalled,” Mattis writes. “The words ‘Equal Justice Under Law’ are carved in the pediment of the United States Supreme Court. This is precisely what protesters are rightly demanding. It is a wholesome and unifying demand—one that all of us should be able to get behind. We must not be distracted by a small number of lawbreakers. The protests are defined by tens of thousands of people of conscience who are insisting that we live up to our values—our values as people and our values as a nation.” He goes on, “We must reject and hold accountable those in office who would make a mockery of our Constitution.” But musically, Fetch astonishes, the work of an artist absolutely confident in the experiment she’s conducting, her objective aligning happily with the listener’s pleasure. This is a true rarity, the artistic advancement that offers joy or surprise or comfort. (I thought of Mitchell’s The Hissing of Summer Lawns or Björk’s Vespertine or David Bowie’s Station to Station.) The album’s tactics—heavy beats, cut-and-paste vocal play—might frustrate some who prefer Apple’s earlier work, waltzy and cutting.

But musically, Fetch astonishes, the work of an artist absolutely confident in the experiment she’s conducting, her objective aligning happily with the listener’s pleasure. This is a true rarity, the artistic advancement that offers joy or surprise or comfort. (I thought of Mitchell’s The Hissing of Summer Lawns or Björk’s Vespertine or David Bowie’s Station to Station.) The album’s tactics—heavy beats, cut-and-paste vocal play—might frustrate some who prefer Apple’s earlier work, waltzy and cutting. The year 1918 was an extraordinary historical moment. As the Great War roared to an end after four long years of blood and horror, it appeared briefly that the future of the world lay wide open. The old order was overthrown. States were collapsing. Monarchs, the sons of dynasties that had ruled eastern and central Europe for centuries, abdicated and fled. Noisy, violent crowds of hungry civilians and grim, weary soldiers flooded grey city streets, demanding peace and a better life. In the countryside, peasants chased away the lords who had ruled over them and seized their land. Mad, bad and dangerous revolutionaries pushing radical ideals and preaching utopia saw that their hour had struck. The German theologian Ernst Troeltsch aptly named this time, when no one had a firm grip on power and anything appeared possible, ‘the dreamland of the armistice period’. These excellent books by Jonathan Schneer and Robert Gerwarth both show just how much was at stake and capture the breathless excitement and mortal fear that the upheaval generated.

The year 1918 was an extraordinary historical moment. As the Great War roared to an end after four long years of blood and horror, it appeared briefly that the future of the world lay wide open. The old order was overthrown. States were collapsing. Monarchs, the sons of dynasties that had ruled eastern and central Europe for centuries, abdicated and fled. Noisy, violent crowds of hungry civilians and grim, weary soldiers flooded grey city streets, demanding peace and a better life. In the countryside, peasants chased away the lords who had ruled over them and seized their land. Mad, bad and dangerous revolutionaries pushing radical ideals and preaching utopia saw that their hour had struck. The German theologian Ernst Troeltsch aptly named this time, when no one had a firm grip on power and anything appeared possible, ‘the dreamland of the armistice period’. These excellent books by Jonathan Schneer and Robert Gerwarth both show just how much was at stake and capture the breathless excitement and mortal fear that the upheaval generated.

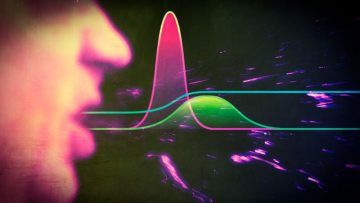

Neuroscientist

Neuroscientist  In our current political climate, it’s sad but not surprising that a U.S. senator would accuse China’s “brightest minds” of studying in America only to return home “to compete for our jobs, to take our business, and ultimately to steal our property.”

In our current political climate, it’s sad but not surprising that a U.S. senator would accuse China’s “brightest minds” of studying in America only to return home “to compete for our jobs, to take our business, and ultimately to steal our property.” Few things are more unexpected than a genuinely inspirational memoir by a freshman member of Congress. If you’re looking for the perfect antidote to the perpetual tweetstorm of insanity and hatred from Donald Trump, try this beautiful new book from the

Few things are more unexpected than a genuinely inspirational memoir by a freshman member of Congress. If you’re looking for the perfect antidote to the perpetual tweetstorm of insanity and hatred from Donald Trump, try this beautiful new book from the  Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Adam Fortais had never attended a virtual conference. Now he’s sold on them — and doesn’t want to go back to conventional, in-person gatherings. That’s because of his experience of helping to instigate some virtual sessions for the March meeting of the American Physical Society (APS), after the organization

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Adam Fortais had never attended a virtual conference. Now he’s sold on them — and doesn’t want to go back to conventional, in-person gatherings. That’s because of his experience of helping to instigate some virtual sessions for the March meeting of the American Physical Society (APS), after the organization

There are some problems for which it’s very hard to find the answer, but very easy to check the answer if someone gives it to you. At least, we think there are such problems; whether or not they really exist is the famous

There are some problems for which it’s very hard to find the answer, but very easy to check the answer if someone gives it to you. At least, we think there are such problems; whether or not they really exist is the famous  One of the least expected aspects of 2020 has been the fact that epidemiological models have become both front-page news and a political football. Public health officials have consulted with epidemiological modelers for decades as they’ve attempted to handle diseases ranging from HIV to the seasonal flu. Before 2020, it had been rare for the role these models play to be recognized outside of this small circle of health policymakers.

One of the least expected aspects of 2020 has been the fact that epidemiological models have become both front-page news and a political football. Public health officials have consulted with epidemiological modelers for decades as they’ve attempted to handle diseases ranging from HIV to the seasonal flu. Before 2020, it had been rare for the role these models play to be recognized outside of this small circle of health policymakers.