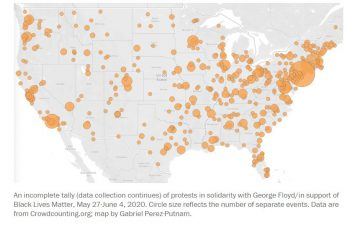

Lara Putnam, Erica Chenoweth and Jeremy Pressman over at the Monkey Cage:

Lara Putnam, Erica Chenoweth and Jeremy Pressman over at the Monkey Cage:

Month: June 2020

Mark Doty Reads ‘A Display of Mackerel’

‘Circles and Squares’ by Caroline Maclean

Rowan Moore at The Guardian:

Artists, wrote the critic Myfanwy Evans in 1937, were in the middle of a thousand battles: “Hampstead, Bloomsbury, surrealist, abstract, social realist, Spain, Germany, heaven, hell, paradise, chaos, light, dark, round, square.” It’s a line that sums up the argumentative world that is the subject of Circles and Squares, one that was ambitious, international and parochial all at once.

Artists, wrote the critic Myfanwy Evans in 1937, were in the middle of a thousand battles: “Hampstead, Bloomsbury, surrealist, abstract, social realist, Spain, Germany, heaven, hell, paradise, chaos, light, dark, round, square.” It’s a line that sums up the argumentative world that is the subject of Circles and Squares, one that was ambitious, international and parochial all at once.

Hampstead and Bloomsbury, it will be noted, are put in the same class of opposition as heaven and hell: different stops along London Transport’s number 24 bus route are compared with the opposing polls of divine cosmic order. Bloomsbury was a slightly older centre of the English avant garde. Hampstead, in the 1930s, attracted a loose group of makers and thinkers who did their best to plant a version of the modernism that had sprung up in continental Europe a decade earlier.

more here.

What is the Grass: Walt Whitman in My Life

David Wheatley at Literary Review:

Academic critics of Dryden or Pope were not in the habit, the last time I checked, of interspersing their monographs with reminiscences of sex clubs in Manhattan. An affectionate excursus on that subject in Mark Doty’s What is the Grass announces that this is no ordinary piece of literary criticism. ‘And your very flesh shall be a great poem,’ wrote Doty’s subject, Walt Whitman, who, one suspects, wouldn’t have minded a bit. Perhaps best known for his 1993 collection My Alexandria, prompted by the AIDS pandemic, Doty is one of the most compelling modern singers of ‘the body electric’ and in What is the Grass he has produced an elegant meditation on the great founding father of American poetry. Not only did Whitman’s example fire up the democratic modern lyrics of W C Williams and Allen Ginsberg; it also licensed poets to place themselves centre stage in their prose, from Adrienne Rich in What is Found There to Susan Howe in her prose-poetry hybrids. It is a licence that Doty seizes on greedily.

Academic critics of Dryden or Pope were not in the habit, the last time I checked, of interspersing their monographs with reminiscences of sex clubs in Manhattan. An affectionate excursus on that subject in Mark Doty’s What is the Grass announces that this is no ordinary piece of literary criticism. ‘And your very flesh shall be a great poem,’ wrote Doty’s subject, Walt Whitman, who, one suspects, wouldn’t have minded a bit. Perhaps best known for his 1993 collection My Alexandria, prompted by the AIDS pandemic, Doty is one of the most compelling modern singers of ‘the body electric’ and in What is the Grass he has produced an elegant meditation on the great founding father of American poetry. Not only did Whitman’s example fire up the democratic modern lyrics of W C Williams and Allen Ginsberg; it also licensed poets to place themselves centre stage in their prose, from Adrienne Rich in What is Found There to Susan Howe in her prose-poetry hybrids. It is a licence that Doty seizes on greedily.

more here.

Saturday Poem

These days

I have turned on the radio.

I have turned off the radio.

I have texted.

I have waited.

I have run from screen to screen,

playing the game of panic,

and I have panicked,

unaccompanied,

with gusto and abandon.

I have waited in line outside of the grocery store,

and waited in line inside of the grocery store,

and comforted a woman in line ahead of me,

overwhelmed by dog food,

and weeping because she had lost her mother.

I have rearranged my life,

and also the plants.

I have mended my black sweater with navy blue thread.

I have waited for the mango to warm up on the table,

I have made tea and scrubbed the dishes,

and learned to measure twenty seconds by heart.

I have witnessed a baptism on church Zoom,

and typed prayers into a chat box.

I have made soup with onions and carrots,

which sweetened the broth unexpectedly.

I have looked for apartments with gardens

and for other apartments with laundry,

and meanwhile I have approximated the spin cycle

by shuffling my feet in soapy water in the tub.

I have pretended to work.

I have given up on reading,

and on patience for language,

and instead I have stood at my north-facing window,

observing the blue jay in the catalpa tree,

and the cardinal in the paper mulberry,

watched their bodies beat with the effort of their calls,

which I have learned, also,

and noted to myself,

blue jay,

cardinal,

and tried to recall

hours later,

as the sun sets, out of view,

somewhere west of this mess of clouds,

pink, at last, at 7 o’clock,

after so many months of darkness.

by Miranda Rose Hall

from 3 Views Theater

how the Black Death changed art forever

Hisham Matar in The Guardian:

Before Italy became a nation, it was made up of a collection of city-states governed by un’autorità superior, in the form of a powerful noble family or a bishop. Siena was an exception in that it favoured civic rule. This partly accounts for the unique character of its art. It produced Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s The Allegory of Good and Bad Government, a series of frescos housed in the Palazzo Pubblico, the civic heart of the city. It is one of the earliest and most significant secular paintings we have. If civic rule were a church, this would be its altarpiece. Siena also imbued its artists with a rare and humanist curiosity that, even in their depictions of religious scenes, involved them in meditations on human psychology and ideas.

Before Italy became a nation, it was made up of a collection of city-states governed by un’autorità superior, in the form of a powerful noble family or a bishop. Siena was an exception in that it favoured civic rule. This partly accounts for the unique character of its art. It produced Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s The Allegory of Good and Bad Government, a series of frescos housed in the Palazzo Pubblico, the civic heart of the city. It is one of the earliest and most significant secular paintings we have. If civic rule were a church, this would be its altarpiece. Siena also imbued its artists with a rare and humanist curiosity that, even in their depictions of religious scenes, involved them in meditations on human psychology and ideas.

This changed with the arrival of the Black Death. The Sienese, like their medieval European Christian counterparts, suffered under the conviction that all diseases came from God. They took the Black Death as proof of their guilt. In the 14th-century Middle English narrative poem Piers Plowman, William Langland puts the matter succinctly: “These pestilences were for pure sin.” The Tuscan poet Petrarch, observing the abandoned bodies of the dead, wrote: “Oh happy people of the future, who have not known these miseries and perchance will class our testimony with the fables. We have, indeed, deserved these [punishments] and even greater.” The church encouraged such supernatural explanations. Many priests refused to bless the infected on the grounds that they were receiving God’s punishment. Most of the believers devoted themselves to prayer and penitential practices, repairing churches and setting up religious houses. The papacy became more powerful. Ideas and the very structure of people’s values shifted.

More here.

This time is different. Here’s why.

Jenna Wortham in The New York Times:

In the wake of a perverse constellation of deaths of black Americans at the hands of the police and vigilantes, America’s current incarnation of a civil rights movement — organized under the rallying cry of “Black Lives Matter” — is more powerful than ever. “Seven years ago, we were treated like we were too radical, too out of the bounds of what is possible,” said Alicia Garza, the civil rights organizer based in Oakland, Calif., who coined the phrase in a 2013 Facebook post after George Zimmerman was acquitted of killing 17-year-old Trayvon Martin. “And now, countless lives later, it’s finally seen as relevant.”

The urgency and validity of the movement have finally been recognized, she told me, as the country has reached “its boiling point.”

For nearly 10 days straight, Americans have been gathering and marching to protest unchecked state violence against black people. Protests have erupted in virtually every American state, in small towns and major cities alike, and in Europe and New Zealand. Dozens of brands published social media posts vocalizing their support for the Black Lives Matter movement or against racism. Some, including those from Ben & Jerry’s, “Sesame Street” and Nickelodeon, felt more explicit and powerful than others. Taylor Swift responded to President Trump’s “when the looting starts, the shooting starts” tweet by accusing him of threatening violence after years of “stoking the fires of white supremacy and racism.” The “Star Wars” actor John Boyega gave an emotional speech at a protest in London.

This is the biggest collective demonstration of civil unrest around state violence in our generation’s memory. The unifying theme, for the first time in America’s history, is at last: Black Lives Matter.

Why now?

Rashad Robinson, the president of the civil rights organization Color of Change, speculated that it was the stark cruelty of the video of George Floyd’s death that captivated the country. The pain was palpable, the nonchalance in Derek Chauvin’s face, chilling. “The police officer is looking into the camera as he’s pushing the life out of him,” Mr. Robinson said.

More here.

One Hundred Years of Hercule Poirot

Aditya Mani Jha in Open:

In 1916, the 26-year-old Agatha Christie finished writing her first detective novel at Dartmoor, a quiet upland in Devon, UK, known for its beautiful granite hilltops. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle had published The Hound of the Baskervilles, in 1902, which would become one of the most widely read Sherlock Holmes adventures—and the story was set in this same corner of the world, Dartmoor.

In 1916, the 26-year-old Agatha Christie finished writing her first detective novel at Dartmoor, a quiet upland in Devon, UK, known for its beautiful granite hilltops. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle had published The Hound of the Baskervilles, in 1902, which would become one of the most widely read Sherlock Holmes adventures—and the story was set in this same corner of the world, Dartmoor.

And with The Mysterious Affair at Styles (published a 100 years ago, in 1920) Christie would introduce readers to Monsieur Hercule Poirot, an old Belgian detective who resembled Holmes superficially (‘eccentric detective, stooge assistant’, as the author would admit in her autobiography later) but whose psychological insights and near-mystical idiosyncrasies would make him arguably the most successful and beloved literary sleuth of all time. Books like Murder on the Orient Express (1934), The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (1926) and Death on the Nile (1937) remain some of the bestselling murder mysteries in the world today, over eight decades after their original publication (Christie’s net sales for all of her books combined are over two billion now).

More here.

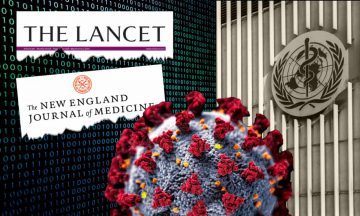

Surgisphere: governments and WHO changed Covid-19 policy based on suspect data from tiny US company

Melissa Davey in Melbourne and Stephanie Kirchgaessner in Washington and Sarah Boseley in London, in The Guardian:

The World Health Organization and a number of national governments have changed their Covid-19 policies and treatments on the basis of flawed data from a little-known US healthcare analytics company, also calling into question the integrity of key studies published in some of the world’s most prestigious medical journals.

The World Health Organization and a number of national governments have changed their Covid-19 policies and treatments on the basis of flawed data from a little-known US healthcare analytics company, also calling into question the integrity of key studies published in some of the world’s most prestigious medical journals.

A Guardian investigation can reveal the US-based company Surgisphere, whose handful of employees appear to include a science fiction writer and an adult-content model, has provided data for multiple studies on Covid-19 co-authored by its chief executive, but has so far failed to adequately explain its data or methodology.

Data it claims to have legitimately obtained from more than a thousand hospitals worldwide formed the basis of scientific articles that have led to changes in Covid-19 treatment policies in Latin American countries. It was also behind a decision by the WHO and research institutes around the world to halt trials of the controversial drug hydroxychloroquine. On Wednesday, the WHO announced those trials would now resume.

Two of the world’s leading medical journals – the Lancet and the New England Journal of Medicine – published studies based on Surgisphere data. The studies were co-authored by the firm’s chief executive, Sapan Desai.

Why we are hard-wired to worry, and what we can do to calm down

James Carmody in The Conversation:

As it turns out, humans are wired to worry. Our brains are continually imagining futures that will meet our needs and things that could stand in the way of them. And sometimes any of those needs may be in conflict with each other.

As it turns out, humans are wired to worry. Our brains are continually imagining futures that will meet our needs and things that could stand in the way of them. And sometimes any of those needs may be in conflict with each other.

Worry is when that vital planning gets the better of us and occupies our attention to no good effect. Tension, sleepless nights, preoccupation and distraction around those very people we care for, worry’s effects are endless. There are ways to tame it, however.

As a professor of medicine and population and quantitative health sciences, I’ve researched and taught mind-body principles to both physicians and patients. I’ve found that there are many methods of quieting the mind and that most of them draw on just a few straightforward principles. Understanding those can help in creatively practicing the techniques in your everyday life.

More here.

The History of the 1918 Flu Pandemic: Three Free Lectures from The Great Courses

via Open Culture

Cold Warriors: Writers Who Waged the Literary Cold War

Randy Boyagoda in First Look:

In the opening lines of Cold Warriors, Duncan White notes that “between February and May 1955, a group covertly funded by the Central Intelligence Agency launched a secret weapon into Communist territory”: balloons carrying copies of George Orwell’s Animal Farm. This was perhaps the most prominent title among “tens of millions of books, leaflets, pamphlets, posters” that were distributed by hundreds of thousands of weather balloons. “In response,” White continues, “the authorities in Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and Poland warned its citizens that possession of this material was illegal and even sought to shoot down the balloons with fighter planes and antiaircraft guns.”

In the opening lines of Cold Warriors, Duncan White notes that “between February and May 1955, a group covertly funded by the Central Intelligence Agency launched a secret weapon into Communist territory”: balloons carrying copies of George Orwell’s Animal Farm. This was perhaps the most prominent title among “tens of millions of books, leaflets, pamphlets, posters” that were distributed by hundreds of thousands of weather balloons. “In response,” White continues, “the authorities in Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and Poland warned its citizens that possession of this material was illegal and even sought to shoot down the balloons with fighter planes and antiaircraft guns.”

Nearly seven hundred pages later, White states the obvious:

Literature is no longer conceived of as a weapon to be deployed in cultural warfare: it is hard to imagine the publication of a novel precipitating a geopolitical crisis in the manner of Dr. Zhivago or The Gulag Archipelago. . . . The specific circumstances of the Cold War will never be repeated, and the idea of literature being deployed by governments on a vast scale is no longer credible.

Of course, governments still worry about writers and writing—China regularly restricts the travel of dissident authors; it goes after booksellers who sell books that criticize the central government; and it bullies foreign embassies, usually Scandinavian, that raise concerns. PEN International regularly documents the situation of imprisoned, suppressed, and disappeared writers living under repressive regimes around the world.

More here.

Is America Becoming a Banana Republic?

Robin Wright in The New Yorker:

In the early nineteen-hundreds, the American writer O. Henry coined the term “banana republic” in a series of short stories, most famously in one about the fictional country of Anchuria. It was based on his experience in Honduras, where he had fled for a few months, to avoid prosecution in Texas, for embezzling money from the bank where he worked. The term—which originally referred to a politically unstable country run by a dictator and his cronies, with an economy dependent on a single product—took on a life of its own. Over the past century, “banana republic” has evolved to mean any country (with or without bananas) that has a ruthless, corrupt, or just plain loopy leader who relies on the military and destroys state institutions in an egomaniacal quest for prolonged power. I’ve covered plenty of them, including Idi Amin’s Uganda, in the nineteen-seventies, Muammar Qaddafi’s Libya, in the nineteen-eighties, and Carlos Menem’s Argentina, in the nineteen-nineties.

In the early nineteen-hundreds, the American writer O. Henry coined the term “banana republic” in a series of short stories, most famously in one about the fictional country of Anchuria. It was based on his experience in Honduras, where he had fled for a few months, to avoid prosecution in Texas, for embezzling money from the bank where he worked. The term—which originally referred to a politically unstable country run by a dictator and his cronies, with an economy dependent on a single product—took on a life of its own. Over the past century, “banana republic” has evolved to mean any country (with or without bananas) that has a ruthless, corrupt, or just plain loopy leader who relies on the military and destroys state institutions in an egomaniacal quest for prolonged power. I’ve covered plenty of them, including Idi Amin’s Uganda, in the nineteen-seventies, Muammar Qaddafi’s Libya, in the nineteen-eighties, and Carlos Menem’s Argentina, in the nineteen-nineties.

Over the past week, however, the President’s response to the escalating protests over the killing of George Floyd has deepened the debate about what is happening to America. The House Speaker, Nancy Pelosi—the third most powerful politician in the the land—described the experience of her daughter, a filmmaker and journalist, when men in fatigues used chemical agents and body armor to force her fellow peaceful protesters aside so Trump could walk to St. John’s Church, on Monday night, for a fleeting photo op where he waved the Bible. On Wednesday, Pelosi bluntly asked, on MSNBC’s “Morning Joe,” “What is this, a banana republic?”

More here.

Friday Poem

Prayer

I will rend my garments like a prophet,

Cover my head with ashes.

I’ll wail if it means you might hear my cry.

I am the patient and the doctor,

The thief and the victim,

The undertaker and the mourner,

The one gasping and the one outside the door.

I am all these things as surely as you are

The creator and destroyer,

The god who eases pain and delivers it,

The god I loved as a child before I had reason,

And now love against it.

I pray to the god who was the soft whisper

after the storm:

I pray to you to hear us, see us,

And weep for us. Weep with us.

God, weep.

If it is true you made us in your image and we have made you in ours,

then there is no hope: you are as reckless as we.

But if is true you are that which passes understanding,

unutterable, unriven, unassailable, inconceivable,

Then to you, I humble myself,

And beg for grace.

Not my will but thy will be done.

I relegate the future, the present and all our poor fates into your hands,

And trust because I must

Not that there is a reason

But that we can survive even without one.

Amen

by Julio Cho

from 3Views Theater

Andy Warhol Eats A Hamburger

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5LDHSBVZpzc

Maxine Hong Kingston’s One Last Big Idea

Hua Hsu at The New Yorker:

The idea for publishing a novel posthumously came to Kingston after learning of Mark Twain’s autobiography, which wasn’t released in uncensored form until 2010, a hundred years after his death. If Kingston knew that she wouldn’t have to answer for her work, perhaps she would be able to write more freely. At first, her notes represented an attempt to capture each day’s “intensity,” she said. In time, she realized that she had written about twelve hundred single-spaced pages. She continued writing. She told her agent, Sandy Dijkstra, that the book would remain unpublished for a hundred years. “I was stunned, shocked, and more,” Dijkstra said in an e-mail, “and told her that I could not promise to be a living and functioning agent a century from now.” Kingston has not shown her any of it. “Maybe you can persuade Maxine to show it to us much sooner,” she said. “Magical thinking works on the page, but not so well in real life.”

The idea for publishing a novel posthumously came to Kingston after learning of Mark Twain’s autobiography, which wasn’t released in uncensored form until 2010, a hundred years after his death. If Kingston knew that she wouldn’t have to answer for her work, perhaps she would be able to write more freely. At first, her notes represented an attempt to capture each day’s “intensity,” she said. In time, she realized that she had written about twelve hundred single-spaced pages. She continued writing. She told her agent, Sandy Dijkstra, that the book would remain unpublished for a hundred years. “I was stunned, shocked, and more,” Dijkstra said in an e-mail, “and told her that I could not promise to be a living and functioning agent a century from now.” Kingston has not shown her any of it. “Maybe you can persuade Maxine to show it to us much sooner,” she said. “Magical thinking works on the page, but not so well in real life.”

more here.

How Not To Write About Andy Warhol

Gary Indiana at Harper’s Magazine:

From time to time, Andy Warhol entertained the wish to host a television show called Nothing Special, and to operate a chain of cafeterias for solitary diners, the Andy-Mat. A social oddity since his Dickensian childhood, Warhol retained the imprint of not-having and not-belonging into adulthood, acquiring vivid people he didn’t much care about and pricey objects he never looked at. To a society poised to reject him, he presented a façade of detachment from other people’s lives, even from his own: in an interview with Alfred Hitchcock, he said that getting shot had been “like watching TV.”

From time to time, Andy Warhol entertained the wish to host a television show called Nothing Special, and to operate a chain of cafeterias for solitary diners, the Andy-Mat. A social oddity since his Dickensian childhood, Warhol retained the imprint of not-having and not-belonging into adulthood, acquiring vivid people he didn’t much care about and pricey objects he never looked at. To a society poised to reject him, he presented a façade of detachment from other people’s lives, even from his own: in an interview with Alfred Hitchcock, he said that getting shot had been “like watching TV.”

What everybody knows about Warhol: He grew up in the Thirties and Forties in a cloacal, polyglot slough of Pittsburgh. He later said it was the worst place he had ever been.

more here.

Quiet Catastrophes

Joshua Craze in n + 1:

In January, I lived in two worlds. In the first, every day contained catastrophes, loud and insistent. Most of them had already happened by the time I woke up and turned on my phone. I would hear from humanitarians reporting casualty numbers from clashes in Jonglei, pastoralists telling me about raids on the Mayom-Warrap border, and politicians whispering about tensions in Juba, South Sudan’s capital. It was morning in America, mid-afternoon in East Africa, and everything seemed to be on fire. I’ve spent a decade working as a conflict researcher in South Sudan, for an alphabet soup of organizations, and I know the slow pace of life across much of the country. In Mayom, despite South Sudan’s ongoing civil war, most of the day is played to the rhythm of the area’s beloved cattle. Raiding takes place alongside milking and grazing. However, if you were to only read my WhatsApp and Signal messages, life in South Sudan would appear to be an endless train-wreck of catastrophes piling up on each other. No one sent me messages about milk. My mornings were spent finding out all I could about the conflict in the country, writing up reports, and then, finally, East Africa would sleep, and my other world could begin.

In January, I lived in two worlds. In the first, every day contained catastrophes, loud and insistent. Most of them had already happened by the time I woke up and turned on my phone. I would hear from humanitarians reporting casualty numbers from clashes in Jonglei, pastoralists telling me about raids on the Mayom-Warrap border, and politicians whispering about tensions in Juba, South Sudan’s capital. It was morning in America, mid-afternoon in East Africa, and everything seemed to be on fire. I’ve spent a decade working as a conflict researcher in South Sudan, for an alphabet soup of organizations, and I know the slow pace of life across much of the country. In Mayom, despite South Sudan’s ongoing civil war, most of the day is played to the rhythm of the area’s beloved cattle. Raiding takes place alongside milking and grazing. However, if you were to only read my WhatsApp and Signal messages, life in South Sudan would appear to be an endless train-wreck of catastrophes piling up on each other. No one sent me messages about milk. My mornings were spent finding out all I could about the conflict in the country, writing up reports, and then, finally, East Africa would sleep, and my other world could begin.

I was staying in a small town in upstate New York, where, I told myself, I could finally sit down, after my last trip to South Sudan, and do some writing.

More here.

Symbolic Mathematics Finally Yields to Neural Networks

Stephen Ornes in Quanta:

By now, people treat neural networks as a kind of AI panacea, capable of solving tech challenges that can be restated as a problem of pattern recognition. They provide natural-sounding language translation. Photo apps use them to recognize and categorize recurrent faces in your collection. And programs driven by neural nets have defeated the world’s best players at games including Go and chess.

By now, people treat neural networks as a kind of AI panacea, capable of solving tech challenges that can be restated as a problem of pattern recognition. They provide natural-sounding language translation. Photo apps use them to recognize and categorize recurrent faces in your collection. And programs driven by neural nets have defeated the world’s best players at games including Go and chess.

However, neural networks have always lagged in one conspicuous area: solving difficult symbolic math problems. These include the hallmarks of calculus courses, like integrals or ordinary differential equations. The hurdles arise from the nature of mathematics itself, which demands precise solutions. Neural nets instead tend to excel at probability. They learn to recognize patterns — which Spanish translation sounds best, or what your face looks like — and can generate new ones.

The situation changed late last year when Guillaume Lample and François Charton, a pair of computer scientists working in Facebook’s AI research group in Paris, unveiled a successful first approach to solving symbolic math problems with neural networks.

More here.