by Anitra Pavlico

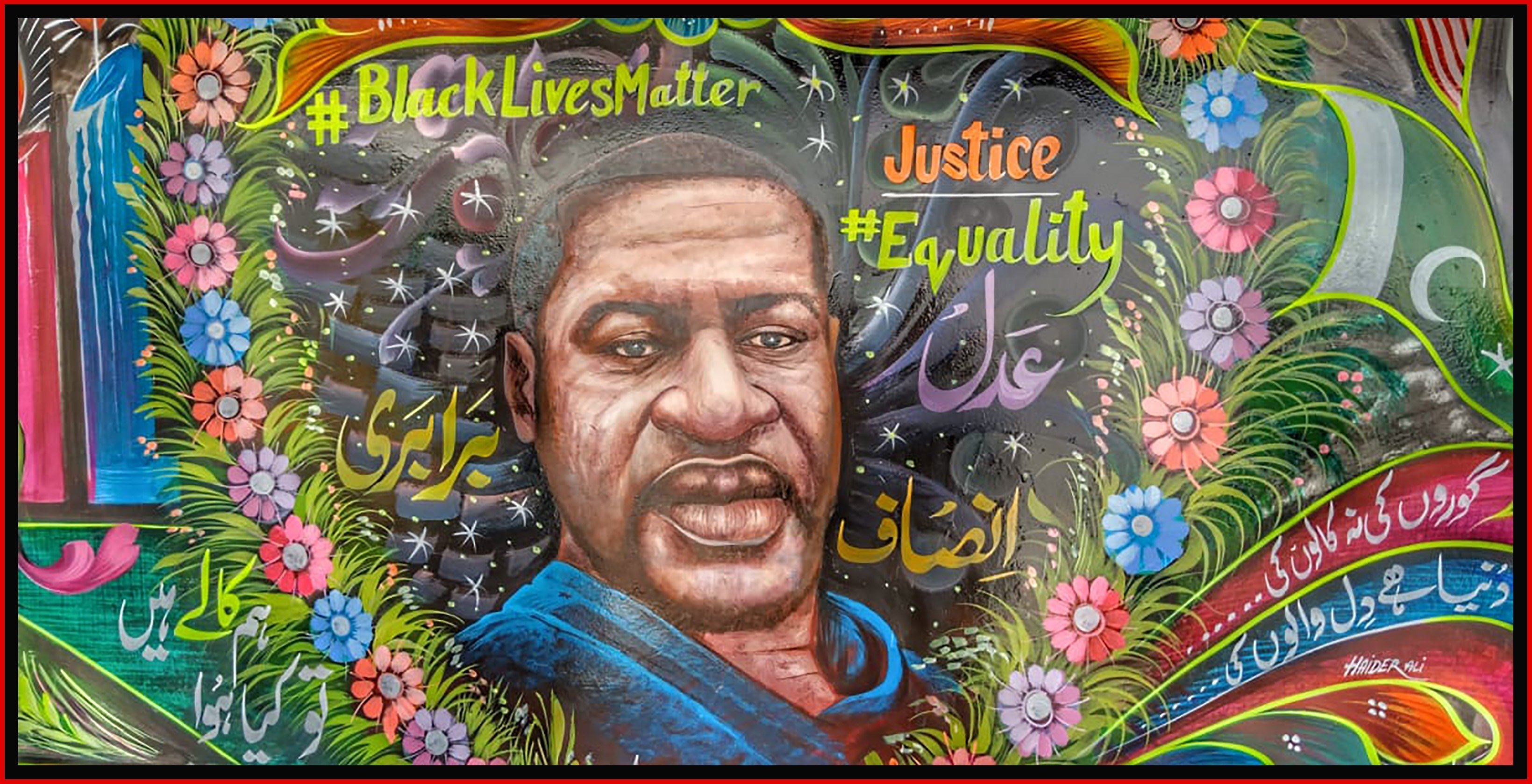

Some police officers are not above bad behavior, even as they work to eradicate and punish it in civilians. It is painfully clear that some of this bad behavior amounts to murder. Civilian review boards are a tool that could punish and deter police misconduct, but they need to have the ability to carry out independent investigations, subpoena documents and witnesses, and issue binding recommendations for discipline. As of a few years ago, only five of the top 50 largest police departments in the U.S. had civilian review boards with disciplinary authority. Newark, New Jersey has recently established such a review board after decades of efforts. While many activists have lost faith in civilian review boards, ACLU director of justice Udi Ofer argues that many of these boards were “rigged to fail.” He says a weak civilian review board is arguably worse than none at all, because it “can lead to an increase in community resentment, as residents go to the board to seek redress yet end up with little.”

Some police officers are not above bad behavior, even as they work to eradicate and punish it in civilians. It is painfully clear that some of this bad behavior amounts to murder. Civilian review boards are a tool that could punish and deter police misconduct, but they need to have the ability to carry out independent investigations, subpoena documents and witnesses, and issue binding recommendations for discipline. As of a few years ago, only five of the top 50 largest police departments in the U.S. had civilian review boards with disciplinary authority. Newark, New Jersey has recently established such a review board after decades of efforts. While many activists have lost faith in civilian review boards, ACLU director of justice Udi Ofer argues that many of these boards were “rigged to fail.” He says a weak civilian review board is arguably worse than none at all, because it “can lead to an increase in community resentment, as residents go to the board to seek redress yet end up with little.”

Ofer says review boards should have a fixed budget, not subject to politicians’ whims, and a majority of board members should be representatives of civic and community organizations. Of the top 50 police departments, 26 have no civilian review board in place at all. Of the remaining 24, all but nine are overseen by a board majority nominated and appointed either by the mayor, or by the mayor in conjunction with the head of police. This hampers the independence of the board when it comes to making disciplinary recommendations. Read more »

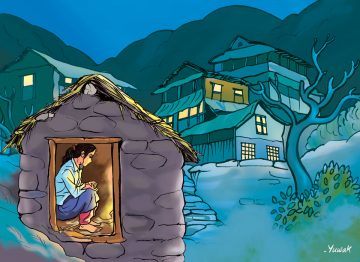

Now that we are witnessing a world that has withdrawn indoors, many people are reading plague literature, discussing Camus and Defoe, and reflecting on the nature of fear and contagion. But there is another kind of literature that lies neglected: stories that reflect the disconnect and dejection of seclusion -the literature of women’s isolation.

Now that we are witnessing a world that has withdrawn indoors, many people are reading plague literature, discussing Camus and Defoe, and reflecting on the nature of fear and contagion. But there is another kind of literature that lies neglected: stories that reflect the disconnect and dejection of seclusion -the literature of women’s isolation. When academics and journalists criticise technology today, they often assume the perspective of a bitter and desperate lover: intimately acquainted with the failings of technology, and vocal in pointing them out, but also too invested and unable to perceive the world without it.

When academics and journalists criticise technology today, they often assume the perspective of a bitter and desperate lover: intimately acquainted with the failings of technology, and vocal in pointing them out, but also too invested and unable to perceive the world without it.

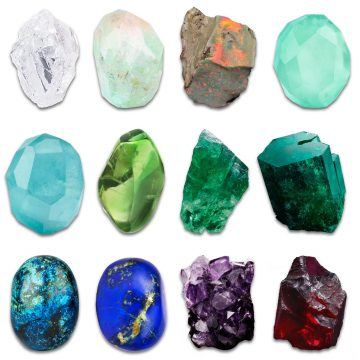

Gems carry a lure that is quintessentially primeval. Considered valuable throughout human history for obvious reasons such as rarity, durability and beauty, gems are inextricable not only from lore, art, architecture, culture, and craft, but also the aesthetics of language. Stories of different civilizations come to us carved in gemstones— Jade figurines of the Forbidden City in Beijing, lapis funerary masks of ancient Egypt, amber encrusted palaces in Moscow, the fabled and famously fought over “koh-i-noor” diamond, the emerald cups and diamond candlesticks of the Ottomans, the bejeweled “peacock throne,” the rubies of Ceylon— and stories manifold to these in words, from myths passed down via the oral tradition, to scripture, fairy tales, poetry and actual accounts of history, to science talk of archeology and gemology.

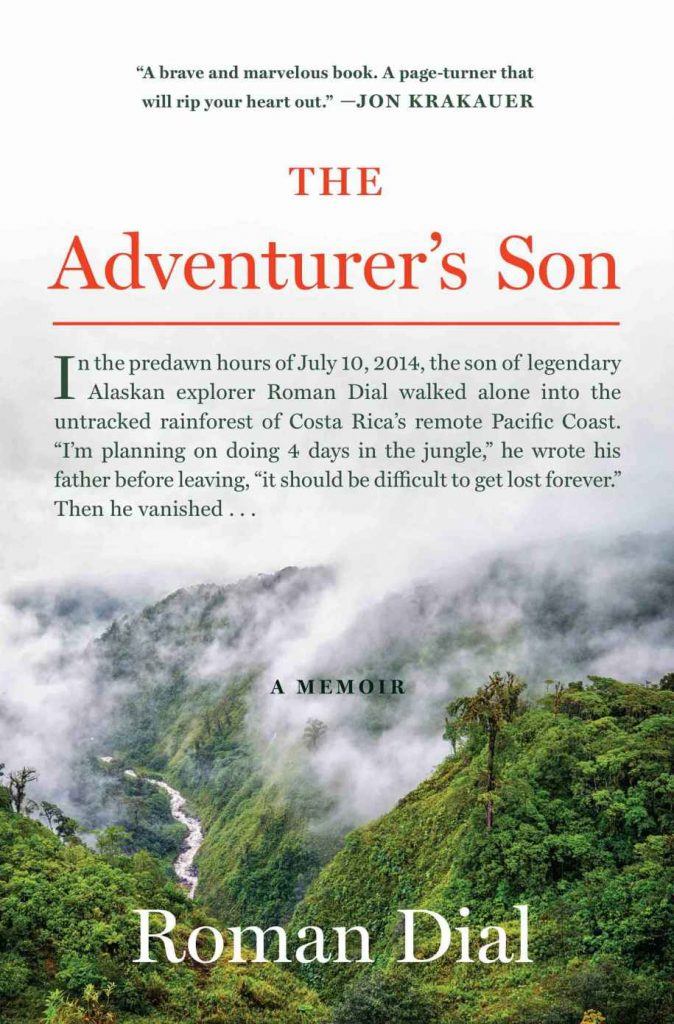

Gems carry a lure that is quintessentially primeval. Considered valuable throughout human history for obvious reasons such as rarity, durability and beauty, gems are inextricable not only from lore, art, architecture, culture, and craft, but also the aesthetics of language. Stories of different civilizations come to us carved in gemstones— Jade figurines of the Forbidden City in Beijing, lapis funerary masks of ancient Egypt, amber encrusted palaces in Moscow, the fabled and famously fought over “koh-i-noor” diamond, the emerald cups and diamond candlesticks of the Ottomans, the bejeweled “peacock throne,” the rubies of Ceylon— and stories manifold to these in words, from myths passed down via the oral tradition, to scripture, fairy tales, poetry and actual accounts of history, to science talk of archeology and gemology. Roman Dial has written a great tribute to his son, indeed to his entire family, in his book The Adventurer’s Son. An adventurer and biologist, Dial writes movingly of his relationship with his only son, Cody Roman Dial in particular and of his accidental death while exploring the rainforests of Central America. Dial’s pride in his son and the pain and grief over his loss are palpable throughout the book. But as Dial himself acknowledges, ‘we never know the future’, and the death of his son at just 27 years old in 2014 is an event he could never have imagined when he began to introduce him to the joys and challenges of exploring the natural world.

Roman Dial has written a great tribute to his son, indeed to his entire family, in his book The Adventurer’s Son. An adventurer and biologist, Dial writes movingly of his relationship with his only son, Cody Roman Dial in particular and of his accidental death while exploring the rainforests of Central America. Dial’s pride in his son and the pain and grief over his loss are palpable throughout the book. But as Dial himself acknowledges, ‘we never know the future’, and the death of his son at just 27 years old in 2014 is an event he could never have imagined when he began to introduce him to the joys and challenges of exploring the natural world. Sometimes it seems life can’t get any worse in this country. Already in terror of a pandemic, Americans have lately been bombarded with images of grotesque state-sponsored violence, from the murder of George Floyd to countless

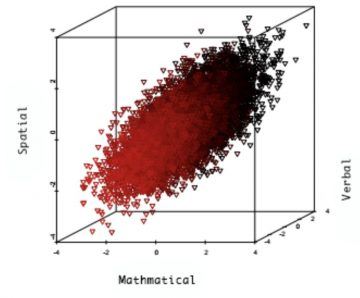

Sometimes it seems life can’t get any worse in this country. Already in terror of a pandemic, Americans have lately been bombarded with images of grotesque state-sponsored violence, from the murder of George Floyd to countless  Lev Landau, a Nobelist and one of the fathers of a great school of Soviet physics, had a logarithmic scale for ranking theorists, from 1 to 5. A physicist in the first class had ten times the impact of someone in the second class, and so on. He modestly ranked himself as 2.5 until late in life, when he became a 2. In the first class were Heisenberg, Bohr, and Dirac among a few others. Einstein was a 0.5!

Lev Landau, a Nobelist and one of the fathers of a great school of Soviet physics, had a logarithmic scale for ranking theorists, from 1 to 5. A physicist in the first class had ten times the impact of someone in the second class, and so on. He modestly ranked himself as 2.5 until late in life, when he became a 2. In the first class were Heisenberg, Bohr, and Dirac among a few others. Einstein was a 0.5! Six errors: 1) missing the compounding effects of masks, 2) missing the nonlinearity of the probability of infection to viral exposures, 3) missing absence of evidence (of benefits of mask wearing) for evidence of absence (of benefits of mask wearing), 4) missing the point that people do not need governments to produce facial covering: they can make their own, 5) missing the compounding effects of statistical signals, 6) ignoring the Non-Aggression Principle by pseudolibertarians (masks are also to protect others from you; it’s a multiplicative process: every person you infect will infect others).

Six errors: 1) missing the compounding effects of masks, 2) missing the nonlinearity of the probability of infection to viral exposures, 3) missing absence of evidence (of benefits of mask wearing) for evidence of absence (of benefits of mask wearing), 4) missing the point that people do not need governments to produce facial covering: they can make their own, 5) missing the compounding effects of statistical signals, 6) ignoring the Non-Aggression Principle by pseudolibertarians (masks are also to protect others from you; it’s a multiplicative process: every person you infect will infect others). This pandemic is closer to a disruption than a crisis or emergency. While all three refer to unexpected and dangerous events requiring immediate action not all involve a rupture. Crises and emergencies have become chronic conditions in finance and politics. This is why we prepare for them through financial contingency plans, safety drills, and disseminating information for the public. These, according to some political scientists, can also socialize people into better democratic habits and attitudes. Disruptions, by contrast, are meant to tear apart our existence. To take a prominent contemporary example, think of the industries that Uber and Amazon have disrupted by offering cheaper services and products.

This pandemic is closer to a disruption than a crisis or emergency. While all three refer to unexpected and dangerous events requiring immediate action not all involve a rupture. Crises and emergencies have become chronic conditions in finance and politics. This is why we prepare for them through financial contingency plans, safety drills, and disseminating information for the public. These, according to some political scientists, can also socialize people into better democratic habits and attitudes. Disruptions, by contrast, are meant to tear apart our existence. To take a prominent contemporary example, think of the industries that Uber and Amazon have disrupted by offering cheaper services and products. The last class Joel Sanders taught in person at the Yale School of Architecture, on Feb. 17, took place in the modern wing of the Yale University Art Gallery, a structure of brick, concrete, glass and steel that was designed by Louis Kahn. It is widely hailed as a masterpiece. One long wall, facing Chapel Street, is windowless; around the corner, a short wall is all windows. The contradiction between opacity and transparency illustrates a fundamental tension museums face, which happened to be the topic of Sanders’s lecture that day: How can a building safeguard precious objects and also display them? How do you move masses of people through finite spaces so that nothing — and no one — is harmed?

The last class Joel Sanders taught in person at the Yale School of Architecture, on Feb. 17, took place in the modern wing of the Yale University Art Gallery, a structure of brick, concrete, glass and steel that was designed by Louis Kahn. It is widely hailed as a masterpiece. One long wall, facing Chapel Street, is windowless; around the corner, a short wall is all windows. The contradiction between opacity and transparency illustrates a fundamental tension museums face, which happened to be the topic of Sanders’s lecture that day: How can a building safeguard precious objects and also display them? How do you move masses of people through finite spaces so that nothing — and no one — is harmed? Annie Zaidi was already a writer of renown in Mumbai when, in 2019, she submitted a 3,000-word essay to the

Annie Zaidi was already a writer of renown in Mumbai when, in 2019, she submitted a 3,000-word essay to the