Clancy Martin in The Economist 1843:

The feeling of being a fraud isn’t new, nor is our preoccupation with it. “All the world’s a stage…And one man in his time plays many parts,” wrote William Shakespeare. The principle of “fake it till you make it” has long propelled incompetents to greatness. The success of phoneys is endlessly fascinating. In the 2000s “On Bullshit”, a book by Harry Frankfurt, a Princeton philosopher, spent many weeks at the top of the New York Times’ bestseller list. But recently we have become fixated on a particular aspect of fraudulence – impostor syndrome – the sense that we are always posturing, that our accomplishments are in some way undeserved, no matter how consistent the evidence to the contrary. Impostor syndrome seems to have become an epidemic. That is partly because we have given the phenomenon a name. Two psychologists, Pauline Clance and Suzanne Imes, are credited with coining the term in a landmark study in the late 1970s, in which they identified the “internal experience” of feeling like an “intellectual phoney”. But our growing preoccupation with impostorism is also a result of profound social change. In the past most people were employed to make things – and it’s fairly easy to distinguish an expert chairmaker or bricklayer from a novice. Many more of us now work in the service economy: our lives are spent creating impressions rather than tangible items. There is no objective standard for providing a “great customer experience”. To be an excellent manager is a nebulous thing. At every level of every field, the number of roles where achievement is neither entirely measurable nor objective has grown.

The feeling of being a fraud isn’t new, nor is our preoccupation with it. “All the world’s a stage…And one man in his time plays many parts,” wrote William Shakespeare. The principle of “fake it till you make it” has long propelled incompetents to greatness. The success of phoneys is endlessly fascinating. In the 2000s “On Bullshit”, a book by Harry Frankfurt, a Princeton philosopher, spent many weeks at the top of the New York Times’ bestseller list. But recently we have become fixated on a particular aspect of fraudulence – impostor syndrome – the sense that we are always posturing, that our accomplishments are in some way undeserved, no matter how consistent the evidence to the contrary. Impostor syndrome seems to have become an epidemic. That is partly because we have given the phenomenon a name. Two psychologists, Pauline Clance and Suzanne Imes, are credited with coining the term in a landmark study in the late 1970s, in which they identified the “internal experience” of feeling like an “intellectual phoney”. But our growing preoccupation with impostorism is also a result of profound social change. In the past most people were employed to make things – and it’s fairly easy to distinguish an expert chairmaker or bricklayer from a novice. Many more of us now work in the service economy: our lives are spent creating impressions rather than tangible items. There is no objective standard for providing a “great customer experience”. To be an excellent manager is a nebulous thing. At every level of every field, the number of roles where achievement is neither entirely measurable nor objective has grown.

Professional life today leaves us straining to redefine ourselves. We no longer have “a job for life”, but instead search endlessly for promotion and variety, which leads us to promise things we don’t yet know how to do. “Pitch culture” has created an environment in which each of us is almost required to be an impostor in order to succeed. The breakdown of class structures has exacerbated this phenomenon. The demise of the feudal system is a good thing, but when we are no longer born into a role, or when we find ourselves in a job that would have been unfamiliar to, or even impossible, for our parents, it’s hardly surprising that we worry about whether or not we deserve it. These social factors also help to explain why the authors of that first academic paper on impostor syndrome immediately identified its greater prevalence and intensity among women rather than men (a finding that later studies have supported). They suggested that both early family dynamics and “societal sex-role stereotyping” meant that many highly successful women they interviewed attributed their achievements to luck, mistaken identity or faulty judgment on the part of their superiors. These same social expectations also probably contribute to the frequent feelings of being an impostor that many people from ethnic minorities also report.

More here.

Socrates, snub-nosed, wall-eyed, paunchy, squat,

Socrates, snub-nosed, wall-eyed, paunchy, squat,

Over the past week, Pakistan has been consumed by the Aurat (Women’s) March, which was held today, March 8, International Women’s Day, in all the major cities of the country. The march’s aim is to highlight the continued discrimination, inequality, and harassment suffered by women. There are some people against it who argue that the march should not be allowed, but the Islamabad High Court has rejected the petition that asked for its cancellation. So the march happened.

Over the past week, Pakistan has been consumed by the Aurat (Women’s) March, which was held today, March 8, International Women’s Day, in all the major cities of the country. The march’s aim is to highlight the continued discrimination, inequality, and harassment suffered by women. There are some people against it who argue that the march should not be allowed, but the Islamabad High Court has rejected the petition that asked for its cancellation. So the march happened. During a recent visit to Paris, I squeezed through the crowded bookshelves of the famous Shakespeare and Company bookstore, a stone’s throw from Notre Dame, whose charred heights sat masked in scaffolding just across the Seine. It has become something of a Parisian tourist hotspot, mostly because of its association with our favorite Modernist expat writers, immortalized and gilded in a cosmopolitan, angsty, and glamorous mystique through the canonization of their works and, some might argue, the award-winning Woody Allen film Midnight in Paris.

During a recent visit to Paris, I squeezed through the crowded bookshelves of the famous Shakespeare and Company bookstore, a stone’s throw from Notre Dame, whose charred heights sat masked in scaffolding just across the Seine. It has become something of a Parisian tourist hotspot, mostly because of its association with our favorite Modernist expat writers, immortalized and gilded in a cosmopolitan, angsty, and glamorous mystique through the canonization of their works and, some might argue, the award-winning Woody Allen film Midnight in Paris.

Research by linguists

Research by linguists

There was this one moment. A sunny June day in Nebraska. No one was around. I dribbled the basketball over the warm blacktop, moving towards a modest hoop erected at the end of a Lutheran church parking lot. I picked up my dribble, took two steps, sprung lightly from my left foot, up and forward, my right arm extending as my hand gracefully served the ball to the white backboard. Its upward angle peaked, bounced softly, and descended back through the netless hoop.

There was this one moment. A sunny June day in Nebraska. No one was around. I dribbled the basketball over the warm blacktop, moving towards a modest hoop erected at the end of a Lutheran church parking lot. I picked up my dribble, took two steps, sprung lightly from my left foot, up and forward, my right arm extending as my hand gracefully served the ball to the white backboard. Its upward angle peaked, bounced softly, and descended back through the netless hoop.

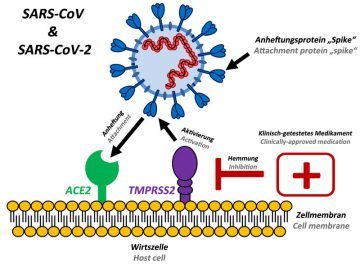

Viruses must enter cells of the human body to cause disease. For this, they attach to suitable cells and inject their genetic information into these cells. Infection biologists from the German Primate Center – Leibniz Institute for Primate Research in Göttingen, together with colleagues at Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, have investigated how the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 penetrates cells. They have identified a cellular enzyme that is essential for viral entry into lung cells: the protease TMPRSS2. A clinically proven drug known to be active against TMPRSS2 was found to block SARS-CoV-2 infection and might constitute a novel treatment option (Cell).

Viruses must enter cells of the human body to cause disease. For this, they attach to suitable cells and inject their genetic information into these cells. Infection biologists from the German Primate Center – Leibniz Institute for Primate Research in Göttingen, together with colleagues at Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, have investigated how the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 penetrates cells. They have identified a cellular enzyme that is essential for viral entry into lung cells: the protease TMPRSS2. A clinically proven drug known to be active against TMPRSS2 was found to block SARS-CoV-2 infection and might constitute a novel treatment option (Cell). Pinker: That would be a stretch. Certainly capitalism deserves credit for the spectacular increase in prosperity that the world has enjoyed since the 18th century, including the global east and south in the past forty years. Prosperity, on average, tends to bring other good things in life: democracy, peace, education, women’s rights, safety, environmental protection, to name a few. Also, the spirit of commerce pushes nations toward peace. It’s bad business to kill your customers or your debtors, and when it’s cheaper to buy things than to steal them, nations are not tempted toward bloody conquest. And as morally corrupting as the pursuit of wealth can be, it’s often less murderous than the pursuit of the glory of the nation, race, or religion.

Pinker: That would be a stretch. Certainly capitalism deserves credit for the spectacular increase in prosperity that the world has enjoyed since the 18th century, including the global east and south in the past forty years. Prosperity, on average, tends to bring other good things in life: democracy, peace, education, women’s rights, safety, environmental protection, to name a few. Also, the spirit of commerce pushes nations toward peace. It’s bad business to kill your customers or your debtors, and when it’s cheaper to buy things than to steal them, nations are not tempted toward bloody conquest. And as morally corrupting as the pursuit of wealth can be, it’s often less murderous than the pursuit of the glory of the nation, race, or religion. As the coronavirus spreads, it is

As the coronavirus spreads, it is  In the summer of 1348, a ship arrived in England, possibly sailing into the port of Southampton, carrying the most deadly cargo ever to reach the British Isles: Yersinia Pestis – bubonic plague. The highly infectious disease had erupted out of Asia, torn through Europe and finally found its way to England where it would devastate the infrastructure of the country, even wiping out entire towns such as Bristol. The symptoms of such a virulent infection were as dramatic as its spread. First a fever, cold and general flu-like symptoms, followed by blackening buboes forming in the joints – most commonly the groin or the armpits, creating its nickname, the Black Death. Sometimes people survived this stage but most commonly the infection would reach the bloodstream and death was inevitable – and usually swift.

In the summer of 1348, a ship arrived in England, possibly sailing into the port of Southampton, carrying the most deadly cargo ever to reach the British Isles: Yersinia Pestis – bubonic plague. The highly infectious disease had erupted out of Asia, torn through Europe and finally found its way to England where it would devastate the infrastructure of the country, even wiping out entire towns such as Bristol. The symptoms of such a virulent infection were as dramatic as its spread. First a fever, cold and general flu-like symptoms, followed by blackening buboes forming in the joints – most commonly the groin or the armpits, creating its nickname, the Black Death. Sometimes people survived this stage but most commonly the infection would reach the bloodstream and death was inevitable – and usually swift. The lions and leopards of Gir National Park, in Gujarat, India, normally do not get along. “They compete with each other” for space and food, said Stotra Chakrabarti, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Minnesota who studies animal behavior. “They are at perpetual odds.” But about a year ago, a young lioness in the park put this enmity aside. She adopted a baby leopard. The 2-month-old cub — all fuzzy ears and blue eyes — was adorable, and the lioness spent weeks nursing, feeding and caring for him until he died. She treated him as if one of her own two sons, who were about the same age. This was a rare case of cross-species adoption in the wild, and the only documented example involving animals that are normally strong competitors, Dr. Chakrabarti said. He

The lions and leopards of Gir National Park, in Gujarat, India, normally do not get along. “They compete with each other” for space and food, said Stotra Chakrabarti, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Minnesota who studies animal behavior. “They are at perpetual odds.” But about a year ago, a young lioness in the park put this enmity aside. She adopted a baby leopard. The 2-month-old cub — all fuzzy ears and blue eyes — was adorable, and the lioness spent weeks nursing, feeding and caring for him until he died. She treated him as if one of her own two sons, who were about the same age. This was a rare case of cross-species adoption in the wild, and the only documented example involving animals that are normally strong competitors, Dr. Chakrabarti said. He