Özden Özer, M.D. is a Hematopathologist at Marmara Leukemia Lymphoma Pathology Laboratory in Istanbul, Turkey. Dr. Özer had her medical training at Marmara University Faculty of Medicine Medical School and pathology training at Northwestern University School of Medicine, McGaw Medical Center, as well as at the University of Chicago where she trained under Drs. Janet Rowley and James Vardiman. Dr. Özer published numerous articles describing her findings in national and international medical journals.

Azra Raza, author of The First Cell: And the Human Costs of Pursuing Cancer to the Last, oncologist and professor of medicine at Columbia University, and 3QD editor, decided to speak to more than 20 leading cancer investigators and ask each of them the same five questions listed below. She videotaped the interviews and over the next months we will be posting them here one at a time each Monday. Please keep in mind that Azra and the rest of us at 3QD neither endorse nor oppose any of the answers given by the researchers as part of this project. Their views are their own. One can browse all previous interviews here.

1. We were treating acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with 7+3 (7 days of the drug cytosine arabinoside and 3 days of daunomycin) in 1977. We are still doing the same in 2019. What is the best way forward to change it by 2028?

2. There are 3.5 million papers on cancer, 135,000 in 2017 alone. There is a staggering disconnect between great scientific insights and translation to improved therapy. What are we doing wrong?

3. The fact that children respond to the same treatment better than adults seems to suggest that the cancer biology is different and also that the host is different. Since most cancers increase with age, even having good therapy may not matter as the host is decrepit. Solution?

4. You have great knowledge and experience in the field. If you were given limitless resources to plan a cure for cancer, what will you do?

5. Offering patients with advanced stage non-curable cancer, palliative but toxic treatments is a service or disservice in the current therapeutic landscape?

If you, like me, have read premodern philosophers not just for antiquarian interest but also as possible sources of wisdom, you will probably have felt a certain awkwardness. Looking for guidance or assistance in ordering our own beliefs, attitudes and actions, we inevitably run into the problem that the great thinkers of the past knew nothing about what our world would look like.

If you, like me, have read premodern philosophers not just for antiquarian interest but also as possible sources of wisdom, you will probably have felt a certain awkwardness. Looking for guidance or assistance in ordering our own beliefs, attitudes and actions, we inevitably run into the problem that the great thinkers of the past knew nothing about what our world would look like.

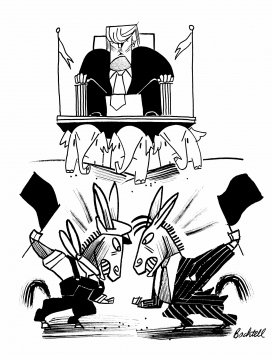

Being a horrible person is all the rage these days. This is, after all, the Age of Trump. But blaming him for it is kinda like blaming raccoons for getting into your garbage after you left the lid off your can. You had to spend a week accumulating all that waste, put it into one huge pile, and then leave it outside over night, unguarded and vulnerable. A lot of time and energy went into creating these delectable circumstances, and now raccoons just bein’ raccoons.

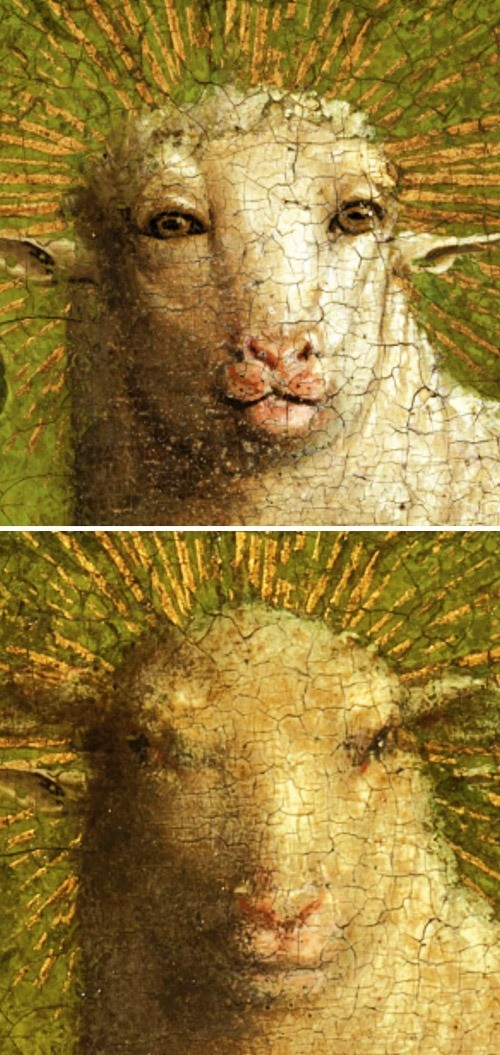

Being a horrible person is all the rage these days. This is, after all, the Age of Trump. But blaming him for it is kinda like blaming raccoons for getting into your garbage after you left the lid off your can. You had to spend a week accumulating all that waste, put it into one huge pile, and then leave it outside over night, unguarded and vulnerable. A lot of time and energy went into creating these delectable circumstances, and now raccoons just bein’ raccoons. Less than a century after the Black Death descended into Europe and killed 75 million people—as much as 60 percent of the population (90% in some places) dead in the five years after 1347—an anonymous Alsatian engraver with the fantastic appellation of “Master of the Playing Cards” saw fit to depict St. Sebastian: the patron saint of plague victims. Making his name, literally, from the series of playing cards he produced at the moment when the pastime first became popular in Germany, the engraver decorated his suits with bears and wolves, lions and birds, flowers and woodwoses. The Master of Playing Cards’s largest engraving, however, was the aforementioned depiction of the unfortunate third-century martyr who suffered by order of the Emperor Diocletian. A violent image, but even several generations after the worst of the Black Death, and Sebastian still resonated with the populace, who remembered that “To many Europeans, the pestilence seemed to be the punishment of a wrathful Creator,” as John Kelly notes in

Less than a century after the Black Death descended into Europe and killed 75 million people—as much as 60 percent of the population (90% in some places) dead in the five years after 1347—an anonymous Alsatian engraver with the fantastic appellation of “Master of the Playing Cards” saw fit to depict St. Sebastian: the patron saint of plague victims. Making his name, literally, from the series of playing cards he produced at the moment when the pastime first became popular in Germany, the engraver decorated his suits with bears and wolves, lions and birds, flowers and woodwoses. The Master of Playing Cards’s largest engraving, however, was the aforementioned depiction of the unfortunate third-century martyr who suffered by order of the Emperor Diocletian. A violent image, but even several generations after the worst of the Black Death, and Sebastian still resonated with the populace, who remembered that “To many Europeans, the pestilence seemed to be the punishment of a wrathful Creator,” as John Kelly notes in  Wuhan is known colloquially as one of the “four furnaces” (四大火炉) of China for its oppressively hot humid summer, shared with Chongqing, Nanjing and alternately Nanchang or Changsha, all bustling cities with long histories along or near the Yangtze river valley. Of the four, Wuhan, however, is also sprinkled with literal furnaces: the massive urban complex acts as a sort of nucleus for the steel, concrete and other construction-related industries of China, its landscape dotted with the slowly-cooling blast furnaces of the remnant state-owned iron and steel foundries, now plagued by

Wuhan is known colloquially as one of the “four furnaces” (四大火炉) of China for its oppressively hot humid summer, shared with Chongqing, Nanjing and alternately Nanchang or Changsha, all bustling cities with long histories along or near the Yangtze river valley. Of the four, Wuhan, however, is also sprinkled with literal furnaces: the massive urban complex acts as a sort of nucleus for the steel, concrete and other construction-related industries of China, its landscape dotted with the slowly-cooling blast furnaces of the remnant state-owned iron and steel foundries, now plagued by  IN THE SUMMER or fall of 1943, La France libre, the London-based provisional government led by General Charles de Gaulle, received a letter from across the Channel. In three closely typed pages, the writer, identifying himself as “un résistant intellectuel,” described the “anguish” he felt as he surveyed the political and moral landscape of Nazi-occupied France. We are teetering, he declared, between renaissance and ruin. Moreover, those struggling on behalf of the former were driven by two often competing ideals: “The clear desire for justice and profound demand for liberty.” Yet, he warned, if we can one day create a doctrine based on these two imperatives, they would lead to the “complete overhaul” of the nation’s constitutional and financial institutions. One way or another, in short, France would never again be the same.

IN THE SUMMER or fall of 1943, La France libre, the London-based provisional government led by General Charles de Gaulle, received a letter from across the Channel. In three closely typed pages, the writer, identifying himself as “un résistant intellectuel,” described the “anguish” he felt as he surveyed the political and moral landscape of Nazi-occupied France. We are teetering, he declared, between renaissance and ruin. Moreover, those struggling on behalf of the former were driven by two often competing ideals: “The clear desire for justice and profound demand for liberty.” Yet, he warned, if we can one day create a doctrine based on these two imperatives, they would lead to the “complete overhaul” of the nation’s constitutional and financial institutions. One way or another, in short, France would never again be the same. Once upon a time, there was a man who thought love was a maths problem.

Once upon a time, there was a man who thought love was a maths problem. Michael Tomasky in the NYRB:

Michael Tomasky in the NYRB: Anthony Paletta in The Boston Review:

Anthony Paletta in The Boston Review: