Toniann Fernandez in The Paris Review:

Toniann Fernandez in The Paris Review:

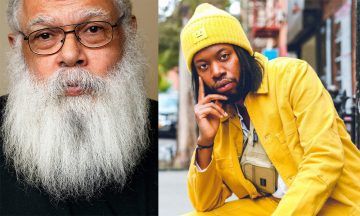

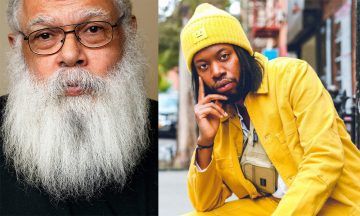

At three in the afternoon on a Friday in late January, Jeremy O. Harris arranged for an Uber to bring Samuel Delany from his home in Philadelphia to the Golden Theatre in New York City. Chip, as the famed writer of science fiction, memoir, essays, and criticism prefers to be called, arrived in Times Square around seven that evening to watch one of the last performances of Harris’s Slave Play on Broadway.

Though the two had never met before, Delany has been hugely influential on Harris, and served as the basis for a character in the latter’s 2019 Black Exhibition, at the Bushwick Starr. And Delany was very aware of Harris. The superstar playwright made an indelible mark on the culture, and it was fitting that the two should meet on Broadway, in Times Square, Delany’s former epicenter of activity, which he detailed at length in his landmark Times Square Red, Times Square Blue and The Mad Man.

After the production, Harris and Delany met backstage. “A lot of famous people have been through here to see this play, but this is everything,” Harris said. The two moved to the Lambs Club, a nearby restaurant that Harris described as “so Broadway that you have to be careful talking about the plays. The person that produced it is probably sitting right behind you.” (Right after saying this, Harris was recognized and enthusiastically greeted by fellow diners.) Over turkey club sandwiches and oysters, Harris and Delany discussed identity, fantasy, kink, and getting turned on in the theater.

More here.

The name Rose Pastor Stokes may no longer be familiar, but Hochschild found plenty of newspaper clippings in his research, along with thousands of letters, unpublished memoirs, Rose’s diary and even reports detailing the surveillance of her by the predecessor of the F.B.I. Unearthing some mournful poetry Rose wrote about her time in the cigar factory, Hochschild corroborates her grim portrait with notes made by a factory inspector. Where information is scant or nonexistent, he deploys elegant workarounds that evoke a vivid sense of time and place. About Graham’s bachelor years before meeting Rose, he writes: “For unmarried men of his class and time, any sexual experience was likely to be furtive and paid for.”

The name Rose Pastor Stokes may no longer be familiar, but Hochschild found plenty of newspaper clippings in his research, along with thousands of letters, unpublished memoirs, Rose’s diary and even reports detailing the surveillance of her by the predecessor of the F.B.I. Unearthing some mournful poetry Rose wrote about her time in the cigar factory, Hochschild corroborates her grim portrait with notes made by a factory inspector. Where information is scant or nonexistent, he deploys elegant workarounds that evoke a vivid sense of time and place. About Graham’s bachelor years before meeting Rose, he writes: “For unmarried men of his class and time, any sexual experience was likely to be furtive and paid for.” Some philosophers—among them MacIntyre, Paul Ricoeur, and Charles Taylor—have insisted that if a narrative is to endow a human life with meaning, it must take the form of a quest for the good. But what makes such a quest an interesting story? There had better be some trouble in it, because that’s what drives a drama. If adversity doesn’t figure prominently in your autobiographical memories, your life narrative will be a bit insipid, and your sense of meaningfulness accordingly impaired.

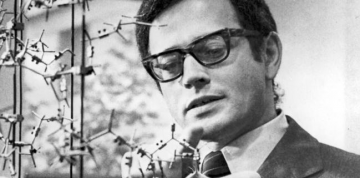

Some philosophers—among them MacIntyre, Paul Ricoeur, and Charles Taylor—have insisted that if a narrative is to endow a human life with meaning, it must take the form of a quest for the good. But what makes such a quest an interesting story? There had better be some trouble in it, because that’s what drives a drama. If adversity doesn’t figure prominently in your autobiographical memories, your life narrative will be a bit insipid, and your sense of meaningfulness accordingly impaired. I would tell you my emotional responses to the gorgeous works in the Donald Judd retrospective that has opened at the Museum of Modern Art if I had any. I was benumbed, as usual, by this last great revolutionary of modern art. The boxy objects (he refused to call them sculptures) that Judd constructed between the early nineteen-sixties and his death, from cancer, in 1994, irreversibly altered the character of Western aesthetic experience. They displaced traditional contemplation with newfangled confrontation. That’s the key trope of Minimalism, a term that Judd despised but one that will tag him until the end of time. In truth, allowing himself certain complexities of structure and color, he was never as radically minimalist as his younger peers Dan Flavin (fluorescent tubes) and Carl Andre (units of raw materials). But Judd, a tremendous art critic and theorist, had foreseen the change (imagine, in theatre, breaking the fourth wall permanently) well before his first show of mature work, in 1963, when he was thirty-five. Slowly, by erosive drip through the nineteen-sixties and seventies, the idea that an exhibition space is integral to the art works that it contains took hold. It is second nature for us now—so familiar that encountering Judd’s works at moma may induce déjà vu.

I would tell you my emotional responses to the gorgeous works in the Donald Judd retrospective that has opened at the Museum of Modern Art if I had any. I was benumbed, as usual, by this last great revolutionary of modern art. The boxy objects (he refused to call them sculptures) that Judd constructed between the early nineteen-sixties and his death, from cancer, in 1994, irreversibly altered the character of Western aesthetic experience. They displaced traditional contemplation with newfangled confrontation. That’s the key trope of Minimalism, a term that Judd despised but one that will tag him until the end of time. In truth, allowing himself certain complexities of structure and color, he was never as radically minimalist as his younger peers Dan Flavin (fluorescent tubes) and Carl Andre (units of raw materials). But Judd, a tremendous art critic and theorist, had foreseen the change (imagine, in theatre, breaking the fourth wall permanently) well before his first show of mature work, in 1963, when he was thirty-five. Slowly, by erosive drip through the nineteen-sixties and seventies, the idea that an exhibition space is integral to the art works that it contains took hold. It is second nature for us now—so familiar that encountering Judd’s works at moma may induce déjà vu. Toniann Fernandez in The Paris Review:

Toniann Fernandez in The Paris Review:

Maria Farrell in The Conversationalist:

Maria Farrell in The Conversationalist: Samanth Subramanian in the New Yorker:

Samanth Subramanian in the New Yorker:

The brain is wider than the sky,

The brain is wider than the sky, In the 2017 film Star Wars: The Last Jedi, the character Finn plans to sacrifice himself for the rebel cause by flying into the glowing-hot core of a giant weapon trained on the rebel hideout. As his rickety vessel speeds toward the target, he is sideswiped off his path by another rebel, Rose. When Finn asks Rose why she prevented his self- sacrifice, she replies: “That’s not how we’re going to win. Not fighting what we hate, [but] saving what we love.” It is difficult to imagine such a scene appearing in earlier Star Wars episodes.

In the 2017 film Star Wars: The Last Jedi, the character Finn plans to sacrifice himself for the rebel cause by flying into the glowing-hot core of a giant weapon trained on the rebel hideout. As his rickety vessel speeds toward the target, he is sideswiped off his path by another rebel, Rose. When Finn asks Rose why she prevented his self- sacrifice, she replies: “That’s not how we’re going to win. Not fighting what we hate, [but] saving what we love.” It is difficult to imagine such a scene appearing in earlier Star Wars episodes. The huge success of the Netflix teen drama series, Sex Education, is partly fuelled by the poor quality of sex ed lessons in schools. Young people are fed up with prudish, vague and incomplete information from their teachers – and parents. So they are turning to the often explicit TV series to get answers.

The huge success of the Netflix teen drama series, Sex Education, is partly fuelled by the poor quality of sex ed lessons in schools. Young people are fed up with prudish, vague and incomplete information from their teachers – and parents. So they are turning to the often explicit TV series to get answers. Las Vegas is a place about which people have ideas. They have thoughts and generalizations, takes and counter-takes, most of them detached from any genuine experience and uninformed by any concrete reality. This is true of many cities—New York, Paris, Prague in the 1990s—owing to books and movies and tourism bureaus, but it is particularly true of Las Vegas. It is a place that looms large in popular culture as a setting for blowout parties and high-stakes gambling, a place where one might wed a stripper with a heart of gold, like Ed Helms does in The Hangover, or hole up in a hotel room and drink oneself to death, as Nicolas Cage does in Leaving Las Vegas. Even those who would never go to Las Vegas are in the grip of its mythology. Yet roughly half of all Americans, or around 165 million people, have visited and one slivery weekend glimpse bestows on them a sense of ownership and authority.

Las Vegas is a place about which people have ideas. They have thoughts and generalizations, takes and counter-takes, most of them detached from any genuine experience and uninformed by any concrete reality. This is true of many cities—New York, Paris, Prague in the 1990s—owing to books and movies and tourism bureaus, but it is particularly true of Las Vegas. It is a place that looms large in popular culture as a setting for blowout parties and high-stakes gambling, a place where one might wed a stripper with a heart of gold, like Ed Helms does in The Hangover, or hole up in a hotel room and drink oneself to death, as Nicolas Cage does in Leaving Las Vegas. Even those who would never go to Las Vegas are in the grip of its mythology. Yet roughly half of all Americans, or around 165 million people, have visited and one slivery weekend glimpse bestows on them a sense of ownership and authority. How do those of us who have enough to eat account for hunger? We often imagine it’s about drought, famine, lack of rain, corruption and incompetence. We need to be much more imaginative. Hunger is about land-grabbing, cartels, early marriage, immunisation, genetically modified crops, child development, slums, climate change, subsidies, chemical pollution, derivative markets, deforestation, child labour, food banks and much, much more. Systemic hunger is about the failure of our food systems and the fact that one half of the world is eating the food of the other half. This is not new. In the 19th century, Europe improved its food availability and quality by importing foodstuffs grown elsewhere.

How do those of us who have enough to eat account for hunger? We often imagine it’s about drought, famine, lack of rain, corruption and incompetence. We need to be much more imaginative. Hunger is about land-grabbing, cartels, early marriage, immunisation, genetically modified crops, child development, slums, climate change, subsidies, chemical pollution, derivative markets, deforestation, child labour, food banks and much, much more. Systemic hunger is about the failure of our food systems and the fact that one half of the world is eating the food of the other half. This is not new. In the 19th century, Europe improved its food availability and quality by importing foodstuffs grown elsewhere. The blur is as close as Mr. Richter has ever come to a stylistic signature, and it recurs here in seascapes, landscapes, and street scenes; portraits of his daughter Betty, her head resting on a table like meat on the butcher block, or his ex-wife, the artist

The blur is as close as Mr. Richter has ever come to a stylistic signature, and it recurs here in seascapes, landscapes, and street scenes; portraits of his daughter Betty, her head resting on a table like meat on the butcher block, or his ex-wife, the artist