by Shadab Zeest Hashmi

“Rapunzel, Rapunzel, let down your hair, so that I may climb the golden stair:” the witch sings to the blonde Rapunzel imprisoned in her tower.

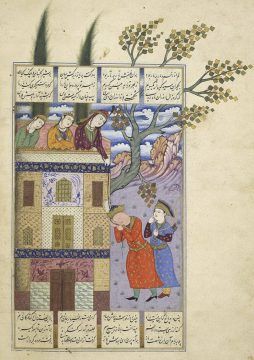

In a legend, Rudabeh, the dark-haired princess of Kabul lets her hair down like a rope for prince Zal to climb up to her tower. She has eyes “like the narcissus and lashes that draw their blackness from the raven’s wing.” Her name is Rudabeh, “child of the river.”

Rapunzel is Brothers Grimms’ nineteenth century retelling of Persinette (1689), which is surmised to be an adaptation of the millennia old Persian legend of Rudabeh, famously recast in Shahnameh, the Persian masterpiece written by the poet Ferdowsi in the eleventh century. Ferdowsi’s lofty praise in his poem set a high bar for the artists who painted the legendary beauty Rudabeh: “about her silvern shoulders two musky black tresses curl, encircling them with their ends as though they were links in a chain.”

The links between such stories from the East and the West emerged first through startling common etymologies in everyday language, songs and stories. As a child tuned in to the world of words, I asked for stories when my mother combed my hair, and caught images and contours of sound in fairy tales in English, the text running from the left to the right and stories of the Alif Laila (One Thousand and One Nights) and Qissa Chahaar Darvish (The Story of the Four Dervishes) in Urdu from the right to left. Read more »

There is a great deal of literature available on the experiences of the horrors, suffering and the injustice that the Jewish people experienced during World War II. Bart Van Es’s The Cut Out Girl adds to that literature.

There is a great deal of literature available on the experiences of the horrors, suffering and the injustice that the Jewish people experienced during World War II. Bart Van Es’s The Cut Out Girl adds to that literature.

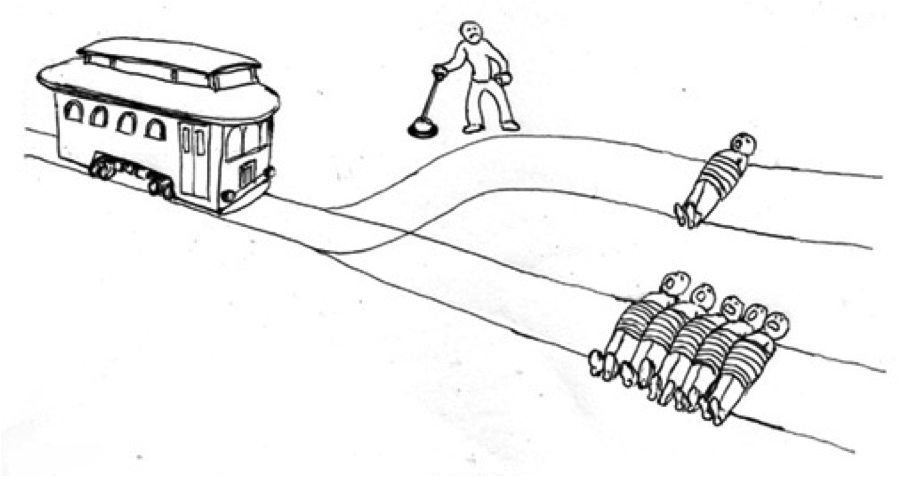

In “The Moral Landscape: How Science Can Determine Human Values” Sam Harris argues that the morally right thing to do is whatever maximizes the welfare or flourishing of human beings. Science “determines human values”, he says, by clarifying what that welfare or flourishing consists of exactly. In an early footnote he complains that “Many of my critics fault me for not engaging more directly with the academic literature on moral philosophy.” But he did not do so, he explains, for two reasons. One is that he did not arrive at his position by reading philosophy, he just came up with it, all on his own, from scratch. The second is because he “is convinced that every appearance of terms like…’deontology’”, etc. “increases the amount of boredom in the universe.”

In “The Moral Landscape: How Science Can Determine Human Values” Sam Harris argues that the morally right thing to do is whatever maximizes the welfare or flourishing of human beings. Science “determines human values”, he says, by clarifying what that welfare or flourishing consists of exactly. In an early footnote he complains that “Many of my critics fault me for not engaging more directly with the academic literature on moral philosophy.” But he did not do so, he explains, for two reasons. One is that he did not arrive at his position by reading philosophy, he just came up with it, all on his own, from scratch. The second is because he “is convinced that every appearance of terms like…’deontology’”, etc. “increases the amount of boredom in the universe.”

We chased the fault line south of Salt Lake City, just past the Cottonwood Canyons, to a small ridge that overlooked a reservoir as silver as the sky. It was October, during a cold drizzle, and the sun was lofted behind the clouds like a shineless mothball. My brother, a Ph.D. student in geology, explained that what appeared to me as indistinct knolls and dips were “expressions” where the fault had deformed the Earth above it. I had spent the day looking at the ground or aiming my eye down my brother’s extended arm to identify subtleties like this. When my gaze finally returned to the Wasatch Mountains, the vision was fresh and horrifying. They were monster-like, tyratnnizing the skyline with their beauty. Under their jagged eminence, my brother and I felt burdened with our knowledge of the region’s fate.

We chased the fault line south of Salt Lake City, just past the Cottonwood Canyons, to a small ridge that overlooked a reservoir as silver as the sky. It was October, during a cold drizzle, and the sun was lofted behind the clouds like a shineless mothball. My brother, a Ph.D. student in geology, explained that what appeared to me as indistinct knolls and dips were “expressions” where the fault had deformed the Earth above it. I had spent the day looking at the ground or aiming my eye down my brother’s extended arm to identify subtleties like this. When my gaze finally returned to the Wasatch Mountains, the vision was fresh and horrifying. They were monster-like, tyratnnizing the skyline with their beauty. Under their jagged eminence, my brother and I felt burdened with our knowledge of the region’s fate. Everyone knows that Turing talked about the imitation game as a way of trying to figure out whether a system is intelligent or not, but what people often don’t appreciate is that in the very same paper, about three paragraphs after the part that everybody quotes, he said, wait a minute, maybe this is the completely wrong track. In fact, what he said was, “Instead of trying to produce a program to simulate the adult mind, why not rather try to produce one which simulates the child?” Then he gives a bunch of examples of how that could be done.

Everyone knows that Turing talked about the imitation game as a way of trying to figure out whether a system is intelligent or not, but what people often don’t appreciate is that in the very same paper, about three paragraphs after the part that everybody quotes, he said, wait a minute, maybe this is the completely wrong track. In fact, what he said was, “Instead of trying to produce a program to simulate the adult mind, why not rather try to produce one which simulates the child?” Then he gives a bunch of examples of how that could be done. In 2017, for the second time in recent years, U.S. life expectancy decreased. Headlines blamed the decline on suicides and opioids, and cast impoverished rural whites as the primary victims. A great deal of attention has been focused on Appalachia, whose population is (erroneously) portrayed as uniformly white, poor, and ravaged by drug addiction. White sickness has thus come to stand for what is supposedly wrong with health, health care, and culture in the United States.

In 2017, for the second time in recent years, U.S. life expectancy decreased. Headlines blamed the decline on suicides and opioids, and cast impoverished rural whites as the primary victims. A great deal of attention has been focused on Appalachia, whose population is (erroneously) portrayed as uniformly white, poor, and ravaged by drug addiction. White sickness has thus come to stand for what is supposedly wrong with health, health care, and culture in the United States. Ignorance involves having a false belief, or no belief at all, on a topic. This can be the result of a simple lack of information. In that case, as soon as we read up on the topic we have knowledge. What distinguishes knowledge resistance, by contrast, is that it cannot be fixed by supplying information. It is, as it were, a type of ignorance that is not easily cured.

Ignorance involves having a false belief, or no belief at all, on a topic. This can be the result of a simple lack of information. In that case, as soon as we read up on the topic we have knowledge. What distinguishes knowledge resistance, by contrast, is that it cannot be fixed by supplying information. It is, as it were, a type of ignorance that is not easily cured. The light is dim, the air richly scented. Little purple tea lights flicker in the votive candle rack and the walls are decorated with twining sunflowers, exuberant passionflowers and several canvases of blousy green carnations monogrammed with Oscar Wilde’s prisoner ID number C.3.3. The Temple is a deconsecrated church with an attractive dark wood ceiling and matching antique chairs. A half-size marble statue of Wilde presides. The artists, McDermott and McGough, have painted various icons spelling out pejoratives such as ‘pansy’, ‘faggot’ and ‘cocksucker’, adorned with gold leaf and richly-coloured paint. Towards the back are intricate woodcut-style depictions of massacres with titles like ‘Nun Cutting Rope of Dead Homeric’, black canvases with cut-out fatality statistics, and monochrome portraits of individuals more recently killed by homophobia and transphobia, such as Justin Fashanu, Brandon Teena and Marsha P. Johnson. A placard in the hallway spells out all of the bigotries the temple stands against, ending with the instruction ‘only love here’. Opposite is a purpose-built offertory box ‘For the Sons and Daughters of Oscar Wilde’.

The light is dim, the air richly scented. Little purple tea lights flicker in the votive candle rack and the walls are decorated with twining sunflowers, exuberant passionflowers and several canvases of blousy green carnations monogrammed with Oscar Wilde’s prisoner ID number C.3.3. The Temple is a deconsecrated church with an attractive dark wood ceiling and matching antique chairs. A half-size marble statue of Wilde presides. The artists, McDermott and McGough, have painted various icons spelling out pejoratives such as ‘pansy’, ‘faggot’ and ‘cocksucker’, adorned with gold leaf and richly-coloured paint. Towards the back are intricate woodcut-style depictions of massacres with titles like ‘Nun Cutting Rope of Dead Homeric’, black canvases with cut-out fatality statistics, and monochrome portraits of individuals more recently killed by homophobia and transphobia, such as Justin Fashanu, Brandon Teena and Marsha P. Johnson. A placard in the hallway spells out all of the bigotries the temple stands against, ending with the instruction ‘only love here’. Opposite is a purpose-built offertory box ‘For the Sons and Daughters of Oscar Wilde’. In the spring of 1883 my mother, Maud Du Puy, came from America to spend the summer in Cambridge with her aunt, Mrs Jebb. She was nearly 22, and had never been abroad before; pretty, affectionate, self-willed, and sociable; but not at all a flirt. Indeed her sisters considered her rather stiff with young men. She was very fresh and innocent, something of a Puritan, and with her strong character, was clearly destined for matriarchy.

In the spring of 1883 my mother, Maud Du Puy, came from America to spend the summer in Cambridge with her aunt, Mrs Jebb. She was nearly 22, and had never been abroad before; pretty, affectionate, self-willed, and sociable; but not at all a flirt. Indeed her sisters considered her rather stiff with young men. She was very fresh and innocent, something of a Puritan, and with her strong character, was clearly destined for matriarchy. It is obvious that the discomfort I once felt over taking antidepressants echoed a lingering, deeply ideological societal mistrust. Articles in the consumer press continue to feed that mistrust. The benefit is ‘mostly modest’, a flawed analysis in The New York Times told us in 2018. A widely shared YouTube

It is obvious that the discomfort I once felt over taking antidepressants echoed a lingering, deeply ideological societal mistrust. Articles in the consumer press continue to feed that mistrust. The benefit is ‘mostly modest’, a flawed analysis in The New York Times told us in 2018. A widely shared YouTube  When a movie starts with a diagnosis of terminal cancer, what next? The first thing we saw in Akira Kurosawa’s “Ikiru” (1952) was an X-ray of a man’s stomach, with a tumor clearly visible, and Lulu Wang’s new film, “The Farewell,” sets off with similar starkness. An aged woman undergoes a CT scan, and we learn that she has Stage IV lung cancer and three months to live. But here’s the difference. Kurosawa’s hero, a meek civil servant, took stock of his mortality and decided to waste not a drop of the time that remained. Wang’s elderly lady, by contrast, is a merry old soul, already skilled at being alive, and requiring no further encouragement. So nobody tells her that she’s going to die.

When a movie starts with a diagnosis of terminal cancer, what next? The first thing we saw in Akira Kurosawa’s “Ikiru” (1952) was an X-ray of a man’s stomach, with a tumor clearly visible, and Lulu Wang’s new film, “The Farewell,” sets off with similar starkness. An aged woman undergoes a CT scan, and we learn that she has Stage IV lung cancer and three months to live. But here’s the difference. Kurosawa’s hero, a meek civil servant, took stock of his mortality and decided to waste not a drop of the time that remained. Wang’s elderly lady, by contrast, is a merry old soul, already skilled at being alive, and requiring no further encouragement. So nobody tells her that she’s going to die.