by Bill Murray

What you pay attention to depends on where you are.

What you pay attention to depends on where you are.

“In an old city, a tourist hears the rumble of wheels over cobblestones that the native does not and notices sound bouncing differently between walls more tightly constructed than in spacious American cities.” – Alexandra Horowitz

She’s right. With the clatter of hoofs from horse-drawn carriages-for -hire in the tourist-center of Dresden a couple of weeks ago, you could see it; the locals plodded on; the tourists perked up and searched out their source.

With sound, personal space is different in different places, too. On the 13th floor of a 21-floor building in Ho Chi Minh City in April, we might as well have been invited guests in the skybar above us. Live Viet Pop invaded our personal earspace the same way a plane flies over your house’s airspace. With utter impunity.

Something else about listening: silence is a sound of its own. After a month in Vietnam, the silence of the Finnish lakeshore, where we are now, is music I was overdue to hear.

Not that it’s entirely silent. Birch leaves rustle like fresh linen sheets. Gulls shriek and shriek at constant calamities. Is there a more easily affronted creature?

On our waterfront this year we have three flocks of ducks, a grebe with an astonishing trail of a dozen babies, and a swan couple with a brood of five. They are doing what they do, growing kids each day, adults teaching kids how to be water birds. Read more »

“America’s epic,” the poet Campbell McGrath writes, “is the odyssey of appetite.” It’s a good line, both clever and seductive, though in the wrong hands it’s the sort of thing that could be merely reductive. But McGrath knows the ins and outs of appetite as deeply, and as thoroughly, as he knows the highways and byways of America. He has spent decades exploring both. “Nouns & Verbs: New and Selected Poems” is a rich and invigorating sampling of the poetic results of these explorations.

“America’s epic,” the poet Campbell McGrath writes, “is the odyssey of appetite.” It’s a good line, both clever and seductive, though in the wrong hands it’s the sort of thing that could be merely reductive. But McGrath knows the ins and outs of appetite as deeply, and as thoroughly, as he knows the highways and byways of America. He has spent decades exploring both. “Nouns & Verbs: New and Selected Poems” is a rich and invigorating sampling of the poetic results of these explorations. GENERAL EQUILIBRIUM THEORY

GENERAL EQUILIBRIUM THEORY Who is secular man, and why is he so unhappy?

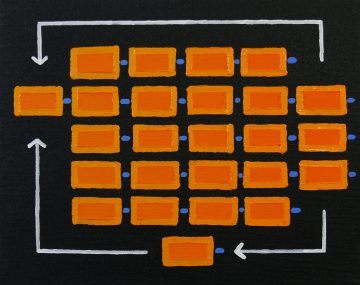

Who is secular man, and why is he so unhappy? Artificial intelligence is an existence proof of one of the great ideas in human history: that the abstract realm of knowledge, reason, and purpose does not consist of an élan vital or immaterial soul or miraculous powers of neural tissue. Rather, it can be linked to the physical realm of animals and machines via the concepts of information, computation, and control. Knowledge can be explained as patterns in matter or energy that stand in systematic relations with states of the world, with mathematical and logical truths, and with one another. Reasoning can be explained as transformations of that knowledge by physical operations that are designed to preserve those relations. Purpose can be explained as the control of operations to effect changes in the world, guided by discrepancies between its current state and a goal state. Naturally evolved brains are just the most familiar systems that achieve intelligence through information, computation, and control. Humanly designed systems that achieve intelligence vindicate the notion that information processing is sufficient to explain it—the notion that the late Jerry Fodor dubbed the computational theory of mind.

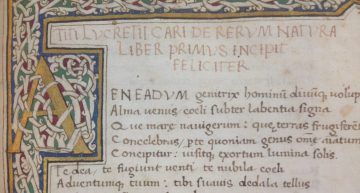

Artificial intelligence is an existence proof of one of the great ideas in human history: that the abstract realm of knowledge, reason, and purpose does not consist of an élan vital or immaterial soul or miraculous powers of neural tissue. Rather, it can be linked to the physical realm of animals and machines via the concepts of information, computation, and control. Knowledge can be explained as patterns in matter or energy that stand in systematic relations with states of the world, with mathematical and logical truths, and with one another. Reasoning can be explained as transformations of that knowledge by physical operations that are designed to preserve those relations. Purpose can be explained as the control of operations to effect changes in the world, guided by discrepancies between its current state and a goal state. Naturally evolved brains are just the most familiar systems that achieve intelligence through information, computation, and control. Humanly designed systems that achieve intelligence vindicate the notion that information processing is sufficient to explain it—the notion that the late Jerry Fodor dubbed the computational theory of mind. ‘The pursuit of Happiness’ is a famous phrase in a famous document, the United States Declaration of Independence (1776). But few know that its author was inspired by an ancient Greek philosopher, Epicurus. Thomas Jefferson considered himself an Epicurean. He probably found the phrase in John Locke, who, like Thomas Hobbes, David Hume and Adam Smith, had also been influenced by Epicurus. Nowadays, educated English-speaking urbanites might call you an epicure if you complain to a waiter about over-salted soup, and stoical if you don’t. In the popular mind, an epicure fine-tunes pleasure, consuming beautifully, while a stoic lives a life of virtue, pleasure sublimated for good. But this doesn’t do justice to Epicurus, who came closest of all the ancient philosophers to understanding the challenges of modern secular life.

‘The pursuit of Happiness’ is a famous phrase in a famous document, the United States Declaration of Independence (1776). But few know that its author was inspired by an ancient Greek philosopher, Epicurus. Thomas Jefferson considered himself an Epicurean. He probably found the phrase in John Locke, who, like Thomas Hobbes, David Hume and Adam Smith, had also been influenced by Epicurus. Nowadays, educated English-speaking urbanites might call you an epicure if you complain to a waiter about over-salted soup, and stoical if you don’t. In the popular mind, an epicure fine-tunes pleasure, consuming beautifully, while a stoic lives a life of virtue, pleasure sublimated for good. But this doesn’t do justice to Epicurus, who came closest of all the ancient philosophers to understanding the challenges of modern secular life. Lodestone, a naturally-occurring iron oxide, was the first persistently magnetic material known to humans. The Han Chinese used it for divining boards 2,200 years ago; ancient Greeks puzzled over why iron was attracted to it; and, Arab merchants placed it in bowls of water to watch the magnet point the way toMecca. In modern times, scientists have used magnets to read and record data on hard drives and form detailed

Lodestone, a naturally-occurring iron oxide, was the first persistently magnetic material known to humans. The Han Chinese used it for divining boards 2,200 years ago; ancient Greeks puzzled over why iron was attracted to it; and, Arab merchants placed it in bowls of water to watch the magnet point the way toMecca. In modern times, scientists have used magnets to read and record data on hard drives and form detailed  Alyssa Battistoni in n+1:

Alyssa Battistoni in n+1: Steven Simon and Jonathan Stevenson in New York Review of Books:

Steven Simon and Jonathan Stevenson in New York Review of Books: John Case in The New Republic:

John Case in The New Republic: T

T I was first alerted to Raymond Geuss’s sour anti-commemoration of Jürgen Habermas’s ninetieth birthday, “

I was first alerted to Raymond Geuss’s sour anti-commemoration of Jürgen Habermas’s ninetieth birthday, “

Gazing at the Moon is an eternal human activity, one of the few things uniting caveman, king and commuter. Each has found something different in that lambent face. For Li Po, a lonely Tang dynasty poet, the Moon was a much-needed drinking buddy. For Holly Golightly, who serenaded it during the “Moon River” scene of “Breakfast at Tiffany’s”, it was a “huckleberry friend” who could whisk her away from her fire escape and her sorrows. By pretending to control a well-timed lunar eclipe, Columbus recruited it to terrify Native Americans into submission. Mussolini superstitiously feared sleeping in its light, and hid from it behind tightly drawn blinds. It would be a challenge for any museum to chronicle the long, complicated relationship humanity has with the Moon, but the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London has done it. For the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 Moon landing, the museum has placed relics from those nine remarkable days in July 1969 alongside cuneiform tablets, Ottoman pocket lunar-calendars, giant Victorian telescopes and instruments designed for India’s first lunar probe in 2008. This impressive exhibition tells the history of humanity’s fascination with this celestial body and looks to the future, as humans attempt once again to return to the Moon.

Gazing at the Moon is an eternal human activity, one of the few things uniting caveman, king and commuter. Each has found something different in that lambent face. For Li Po, a lonely Tang dynasty poet, the Moon was a much-needed drinking buddy. For Holly Golightly, who serenaded it during the “Moon River” scene of “Breakfast at Tiffany’s”, it was a “huckleberry friend” who could whisk her away from her fire escape and her sorrows. By pretending to control a well-timed lunar eclipe, Columbus recruited it to terrify Native Americans into submission. Mussolini superstitiously feared sleeping in its light, and hid from it behind tightly drawn blinds. It would be a challenge for any museum to chronicle the long, complicated relationship humanity has with the Moon, but the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London has done it. For the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 Moon landing, the museum has placed relics from those nine remarkable days in July 1969 alongside cuneiform tablets, Ottoman pocket lunar-calendars, giant Victorian telescopes and instruments designed for India’s first lunar probe in 2008. This impressive exhibition tells the history of humanity’s fascination with this celestial body and looks to the future, as humans attempt once again to return to the Moon. In the early days of the run-up to the 2016 election, I was just beginning to prepare a class on whiteness to teach at Yale University, where I had been newly hired. Over the years, I had come to realize that I often did not share historical knowledge with the persons to whom I was speaking. “What’s redlining?” someone would ask. “George Washington freed his slaves?” someone else would inquire. But as I listened to Donald Trump’s inflammatory rhetoric during the campaign that spring, the class took on a new dimension. Would my students understand the long history that informed a comment like one Trump made when he announced his presidential candidacy? “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best,” he said. “They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.” When I heard those words, I wanted my students to track immigration laws in the United States. Would they connect the treatment of the undocumented with the treatment of Irish, Italian and Asian people over the centuries?

In the early days of the run-up to the 2016 election, I was just beginning to prepare a class on whiteness to teach at Yale University, where I had been newly hired. Over the years, I had come to realize that I often did not share historical knowledge with the persons to whom I was speaking. “What’s redlining?” someone would ask. “George Washington freed his slaves?” someone else would inquire. But as I listened to Donald Trump’s inflammatory rhetoric during the campaign that spring, the class took on a new dimension. Would my students understand the long history that informed a comment like one Trump made when he announced his presidential candidacy? “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best,” he said. “They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.” When I heard those words, I wanted my students to track immigration laws in the United States. Would they connect the treatment of the undocumented with the treatment of Irish, Italian and Asian people over the centuries? Walter Gropius was fond of making claims about The Bauhaus like the following: “Our guiding principle was that design is neither an intellectual nor a material affair, but simply an integral part of the stuff of life, necessary for everyone in a civilized society.” Idealistic and vague, perhaps to a fault, but one gets the point. Bauhaus design was never intended to be alienating. It was supposed to be the opposite. It was supposed to preserve the relative “health” of the craft traditions while marching boldly into a new era. It was supposed to help cure the potential wounds of modern life, wounds caused, initially, by the industrial revolution and its jarring impact on everything from the natural landscape to the material and design of our cutlery. Anti-alienation was really the one guiding intuition behind The Bauhaus as a school and then, more amorphously, as a general approach to architecture and design.

Walter Gropius was fond of making claims about The Bauhaus like the following: “Our guiding principle was that design is neither an intellectual nor a material affair, but simply an integral part of the stuff of life, necessary for everyone in a civilized society.” Idealistic and vague, perhaps to a fault, but one gets the point. Bauhaus design was never intended to be alienating. It was supposed to be the opposite. It was supposed to preserve the relative “health” of the craft traditions while marching boldly into a new era. It was supposed to help cure the potential wounds of modern life, wounds caused, initially, by the industrial revolution and its jarring impact on everything from the natural landscape to the material and design of our cutlery. Anti-alienation was really the one guiding intuition behind The Bauhaus as a school and then, more amorphously, as a general approach to architecture and design.