James Wang at Eurozine:

In short, Western narratives about China throughout the 1990s hinged on the logic that capitalist development must end with liberal democracy. In hindsight, however, precisely the opposite seems to have occurred in the People’s Republic. Rather than being a political albatross on the Party’s neck, the legacy of Tiananmen, the chaotic aftermath of Soviet collapse, and the difficulties in bridging east-west divisions in Europe, has paradoxically bolstered the Party’s legitimacy in China. Indeed, public opinion surveys in recent years have consistently found that a majority of Chinese citizens are not only content with the Party’s leadership but broadly more optimistic about their personal future and that of their country relative to those polled in the West. The same surveys also found that Chinese people tend to be unsympathetic to proposals for major shifts in China’s current political framework. Moreover, positive opinions regarding one-party rule in China seem to have consistently grown in the last two decades.

In short, Western narratives about China throughout the 1990s hinged on the logic that capitalist development must end with liberal democracy. In hindsight, however, precisely the opposite seems to have occurred in the People’s Republic. Rather than being a political albatross on the Party’s neck, the legacy of Tiananmen, the chaotic aftermath of Soviet collapse, and the difficulties in bridging east-west divisions in Europe, has paradoxically bolstered the Party’s legitimacy in China. Indeed, public opinion surveys in recent years have consistently found that a majority of Chinese citizens are not only content with the Party’s leadership but broadly more optimistic about their personal future and that of their country relative to those polled in the West. The same surveys also found that Chinese people tend to be unsympathetic to proposals for major shifts in China’s current political framework. Moreover, positive opinions regarding one-party rule in China seem to have consistently grown in the last two decades.

In the Party’s own triumphalist narrative, 1991 and 1999 stand out as two watershed moments. From Beijing’s perspective, the anarchy of the collapse of the Soviet Union, and Yeltsin’s cynical crushing of parliamentary opposition, furnished a perfect counter-narrative to June 4th, 1989. As Russia, China’s former Cold War arch-rival, sank into economic freefall, rampant corruption, and a period of geopolitical irrelevancy, China’s communist party leadership was able to guarantee political stability and engineered three decades of uninterrupted economic growth.

more here.

Great reporting isn’t usually harmed by the reporter having a poor character. It may even be improved by it. Lillian just happened to be hard-bitten in the right way. Her pieces relied on a ruthlessness, sometimes a viciousness, that she didn’t try to hide and that other people liked to comment on. She talked a lot about not being egotistical and so on, but reporters who talk a great deal about not obtruding on the reporting are usually quite aware, at some level, that objectivity is probably a fiction, and that they are most present when imagining they’re invisible. (Lillian was in at least two minds about this, possibly six. One minute she’d say a reporter had to let the story be the story, the next she’d say it was ridiculous: a reporter is ‘chemically’ involved in the story she is writing.) By the time I knew her, Lillian was struggling against a sense that she had caused pain to Shawn’s widow, Cecille, who was still alive, and permanently changed the public view of that most quiet and dedicated of New Yorker editors. Though I liked the book, I believed she was fooling herself if she thought there wasn’t something more than candour at work in her portrayal of Shawn’s family and the reality of his life with them. She claimed she was his ‘real’ wife and that her adopted son, Erik, was ‘theirs’. She knew this was tendentious and took out her anxiety on people who pointed it out.

Great reporting isn’t usually harmed by the reporter having a poor character. It may even be improved by it. Lillian just happened to be hard-bitten in the right way. Her pieces relied on a ruthlessness, sometimes a viciousness, that she didn’t try to hide and that other people liked to comment on. She talked a lot about not being egotistical and so on, but reporters who talk a great deal about not obtruding on the reporting are usually quite aware, at some level, that objectivity is probably a fiction, and that they are most present when imagining they’re invisible. (Lillian was in at least two minds about this, possibly six. One minute she’d say a reporter had to let the story be the story, the next she’d say it was ridiculous: a reporter is ‘chemically’ involved in the story she is writing.) By the time I knew her, Lillian was struggling against a sense that she had caused pain to Shawn’s widow, Cecille, who was still alive, and permanently changed the public view of that most quiet and dedicated of New Yorker editors. Though I liked the book, I believed she was fooling herself if she thought there wasn’t something more than candour at work in her portrayal of Shawn’s family and the reality of his life with them. She claimed she was his ‘real’ wife and that her adopted son, Erik, was ‘theirs’. She knew this was tendentious and took out her anxiety on people who pointed it out. Before he became an internet sensation, before he made scientists reconsider the nature of dancing, before the

Before he became an internet sensation, before he made scientists reconsider the nature of dancing, before the  Scientists

Scientists  A British friend of mine once told me that when he feels stressed he often turns to re-reading R.K. Narayan’s stories about Malgudi, the fictional placid small town in south India. Much earlier, in the 1930’s, a fellow-Britisher, the writer Graham Greene, had discovered Narayan and became his life-long friend, mentor, agent for the wider literary world, and even occasional proof-reader. He found a kind of ‘sadness and beauty’ in Narayan’s simple depiction of the idiosyncrasies and disappointments of ordinary lives which he imbues with a touching sense of gentle irony and compassion.

A British friend of mine once told me that when he feels stressed he often turns to re-reading R.K. Narayan’s stories about Malgudi, the fictional placid small town in south India. Much earlier, in the 1930’s, a fellow-Britisher, the writer Graham Greene, had discovered Narayan and became his life-long friend, mentor, agent for the wider literary world, and even occasional proof-reader. He found a kind of ‘sadness and beauty’ in Narayan’s simple depiction of the idiosyncrasies and disappointments of ordinary lives which he imbues with a touching sense of gentle irony and compassion. I shall start with the third, titled Between the Assassinations by Aravind Adiga, which is probably the furthest of the three in terms of dissonance from the life in Malgudi. Here we can definitely say: Toto, we are not in Malgudi anymore. The assassinations referred to are those of Indira Gandhi in 1984 and of her son, Rajiv Gandhi, in 1991, but in the book except for merely as a time-marker of those 7 years, they do not play any direct role. Adiga came to be widely noted after he won the Booker Prize for his short novel The White Tiger, a book of stridently raging fury at the crushing inequalities and depravity arising from India’s roaring economic growth and somewhat cardboard characters through which they are played out, a book I did not particularly like. Adiga wrote Between the Assassinations earlier but published it after The White Tiger. Here the fury is less strident, there is more nuance and variety in the characters, and along with aching sympathy there is all-enveloping hopelessness. Here is a typical scene: a lowly cart-rickshaw puller, straining hard going uphill with a heavy load, exhausted by the heat and humiliation and a painful neck, stops his cart in the middle of the busy road, shakes his fist in a futile gesture at the passing, honking traffic and shouts: ‘Don’t you see something is wrong with this world?’

I shall start with the third, titled Between the Assassinations by Aravind Adiga, which is probably the furthest of the three in terms of dissonance from the life in Malgudi. Here we can definitely say: Toto, we are not in Malgudi anymore. The assassinations referred to are those of Indira Gandhi in 1984 and of her son, Rajiv Gandhi, in 1991, but in the book except for merely as a time-marker of those 7 years, they do not play any direct role. Adiga came to be widely noted after he won the Booker Prize for his short novel The White Tiger, a book of stridently raging fury at the crushing inequalities and depravity arising from India’s roaring economic growth and somewhat cardboard characters through which they are played out, a book I did not particularly like. Adiga wrote Between the Assassinations earlier but published it after The White Tiger. Here the fury is less strident, there is more nuance and variety in the characters, and along with aching sympathy there is all-enveloping hopelessness. Here is a typical scene: a lowly cart-rickshaw puller, straining hard going uphill with a heavy load, exhausted by the heat and humiliation and a painful neck, stops his cart in the middle of the busy road, shakes his fist in a futile gesture at the passing, honking traffic and shouts: ‘Don’t you see something is wrong with this world?’

Mother’s friend departed after their weekly get-together for tea, cakes and gossip, but she forgot to take her book. It was a slim hardback with the blue and yellow banded cover of a subscription book club. It lay on the arm of the sofa for ten minutes and then, before anybody noticed, it vanished – relocated to my bedroom. I was fifteen, and this would be the first adult novel I had ever read. Its title was Under the Net by Iris Murdoch. Iris was my “first” – first adult novelist and first woman writer, and she has remained fixed in my affections over the decades. Under the Net was also Murdoch’s first novel, published in 1954. I was so naively charmed that I made a precocious promise to myself to reread it fifteen years later to see if its appeal lasted. I already knew that in the coming years I would not be rereading my previous favourites, my childhood book collections of Just William, Biggles, Billy Bunter and John Carter’s adventures on Mars. Unlike them, Under the Net had mysteries and ideas I did not yet fathom, but would need to discover.

Mother’s friend departed after their weekly get-together for tea, cakes and gossip, but she forgot to take her book. It was a slim hardback with the blue and yellow banded cover of a subscription book club. It lay on the arm of the sofa for ten minutes and then, before anybody noticed, it vanished – relocated to my bedroom. I was fifteen, and this would be the first adult novel I had ever read. Its title was Under the Net by Iris Murdoch. Iris was my “first” – first adult novelist and first woman writer, and she has remained fixed in my affections over the decades. Under the Net was also Murdoch’s first novel, published in 1954. I was so naively charmed that I made a precocious promise to myself to reread it fifteen years later to see if its appeal lasted. I already knew that in the coming years I would not be rereading my previous favourites, my childhood book collections of Just William, Biggles, Billy Bunter and John Carter’s adventures on Mars. Unlike them, Under the Net had mysteries and ideas I did not yet fathom, but would need to discover.

Nature has filled the world with “endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful,” in the words of Charles Darwin. We humans, faced with this abundance and variety of creatures, have used our imagination to the full in giving them descriptive and often evocative names. Some animal names are fairly straightforward; the name big hairy armadillo lacks nuance, although it makes up in charm what it lacks in subtlety. In other cases, though, we’ve come up with epithets that would make a poet proud: the tawny-crowned greenlet, the sharp-shinned hawk, the pricklenape lizards.

Nature has filled the world with “endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful,” in the words of Charles Darwin. We humans, faced with this abundance and variety of creatures, have used our imagination to the full in giving them descriptive and often evocative names. Some animal names are fairly straightforward; the name big hairy armadillo lacks nuance, although it makes up in charm what it lacks in subtlety. In other cases, though, we’ve come up with epithets that would make a poet proud: the tawny-crowned greenlet, the sharp-shinned hawk, the pricklenape lizards.

Whether we’re glancing through a play from high school before donating it or wandering through an antique shop, sometimes we see a word that doesn’t look quite right. Sometimes, misspelled words are a result of advertising campaigns, and other times they are alternate spellings in English. We all know English has some demented rules of orthography (even the word “orthography” can inspire chuckles; “proper writing” in English? Is that a joke?). You’re not alone if you have to remind yourself about “i before e except after c” and its numerous exceptions.

Whether we’re glancing through a play from high school before donating it or wandering through an antique shop, sometimes we see a word that doesn’t look quite right. Sometimes, misspelled words are a result of advertising campaigns, and other times they are alternate spellings in English. We all know English has some demented rules of orthography (even the word “orthography” can inspire chuckles; “proper writing” in English? Is that a joke?). You’re not alone if you have to remind yourself about “i before e except after c” and its numerous exceptions.

When did nature become a good for cities? When did city dwellers start imagining nature to be something they were missing? Today, urbanites’ moral associations with nature are so obvious and widely shared that a recent New Yorker cartoon of a couple at the dinner table was captioned: “Is this from the community garden? It tastes sanctimonious.” For better or worse, most of us are so steeped in this view of nature that it is hard to imagine how it could be otherwise. But it once was.

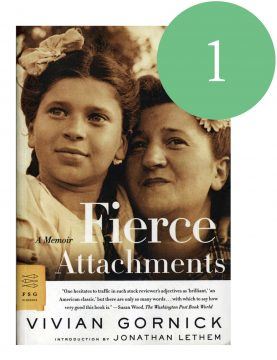

When did nature become a good for cities? When did city dwellers start imagining nature to be something they were missing? Today, urbanites’ moral associations with nature are so obvious and widely shared that a recent New Yorker cartoon of a couple at the dinner table was captioned: “Is this from the community garden? It tastes sanctimonious.” For better or worse, most of us are so steeped in this view of nature that it is hard to imagine how it could be otherwise. But it once was. “I remember only the women,” Vivian Gornick writes near the start of her memoir of growing up in the Bronx tenements in the 1940s, surrounded by the blunt, brawling, yearning women of the neighborhood, chief among them her indomitable mother. “I absorbed them as I would chloroform on a cloth laid against my face. It has taken me 30 years to understand how much of them I understood.”

“I remember only the women,” Vivian Gornick writes near the start of her memoir of growing up in the Bronx tenements in the 1940s, surrounded by the blunt, brawling, yearning women of the neighborhood, chief among them her indomitable mother. “I absorbed them as I would chloroform on a cloth laid against my face. It has taken me 30 years to understand how much of them I understood.”